A 33-Year Shadow

By Babar Ayaz | Special Report | Published 8 years ago

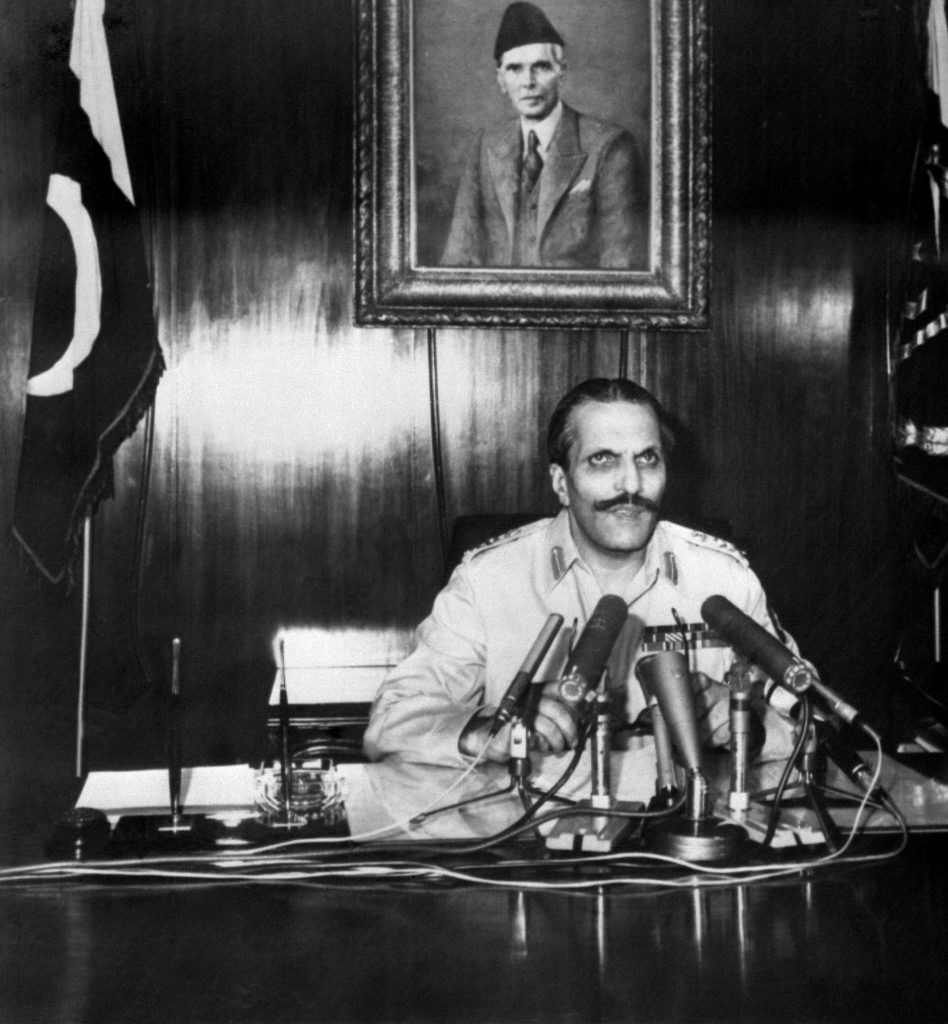

General Muhammad Zia-Ul-Haq adresses the nation after announcing martial law in July 1977.

In Pakistan’s short 70-year history, military dictators ruled the country directly, for 33 years. Even when the military was not in power, its long shadow haunted civilian governments, who accused them of keeping all political dispensations unstable through covert intrigues, and hindering the democratic evolution of the country. General Ayub Khan abrogated the 1956 Constitution and established the first martial law government that lasted for 10 years; he launched a clandestine military operation in Indian-administered Kashmir, which resulted in provoking an all-out war with India and ignored the exploitation of East Pakistan. Yahya, on the other hand, launched a military operation against East Pakistan, which was ruled as a colony by West Pakistan’s elite for 24 years. As a result, the country broke. General (R) Pervez Musharraf launched the Kargil adventure, which brought us close to war with India and, ultimately, left us humiliated as our troops were forced to retreat. He tried to pull a fast one on the US by continuing to support the Afghan Taliban and the jihadi groups that targeted not just India, but subsequently wreaked havoc in Pakistan as well.

Yet it was General Zia-ul-Haq’s rule that did the most damage to the country. Zia took over on July 5, 1977, deposing Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s elected government. He converted political Islam into militant Islam, thus unleashing the forces of terrorism and sectarianism. For the last 40 years, the country has bled, thanks to the jihad launched by Zia’s regime, at the US government’s behest, to dislodge the socialist government in Afghanistan in 1979. For 10 years the so-called Islamic jihadists of Afghanistan were provided free weapons by the US.

There was a general consensus among the journalists covering the Afghanistan insurgency in the 80s, that almost 70 per cent of the arms and ammunition given to these mujahideen were sold by them to the people in Pakistan. At the same time, heroin smuggling was used to fund the militant leaders, making drug addiction a serious problem in the country.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was hijacked by the Shia clergy. This rattled Saudi Arabia’s Wahabi government. The Saudis started financing sectarian Sunni militant organisations in Pakistan, while the Iranian government backed the Shias. And thus began Pakistan’s proxy sectarian war.

Zia booted out his benefactor, the then prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. He cunningly manipulated the judiciary at the highest level to get Bhutto hanged — the same Bhutto who had appointed Zia as army chief, superseding seven generals.

Under the leadership of Zia, who was at the time stationed in Jordan as a brigadier, the Pakistan Army conducted operations against the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). According to a spokesperson for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Zia was responsible for the murder of 25,000 Palestinians protesting against King Hussain’s government. The Palestinians named this uprising and massacre ‘Black September.’ They remembered him as ‘Zia ul Qasab.’

When he was appointed the army chief, I asked a friend in the army — a junior officer who had served under him — about the kind of person Zia was. “Cunning and cannot be trusted,” was the reply.

After the 1977 coup, I had the opportunity to ask General Tikka Khan, the then secretary general of the Pakistan People`s Party (PPP), why Bhutto picked Zia as the army chief. Tikka Khan shared that an attempted coup by young military officers had been crushed, thanks to intelligence reports by Lieutenant General Jillani, the head of Military Intelligence. All the young officers were arrested and court-martialled in Attock Fort. Since the plotters were popular among their peers and some of them were related to senior army officers, Bhutto asked Jillani to give them befitting punishments. Jillani suggested the name of Zia and said that he would do whatever the prime minister desired. And sure enough, the military court, presided over by Zia, gave maximum punishment to the officers. This was what convinced Bhutto that Zia would remain loyal to him.

That Zia was an unscrupulous opportunist can be deduced from an incident narrated by senior journalist,

S. M. Uzair, who was working with APP, a news agency, and was stationed at Attock Fort to report on the trial of the young officers. Before publishing the report, he would always have to run it by Zia. According to Uzair, Zia used to praise the young officers, who had plotted the coup, profusely. Back then, Uzair thought that since Zia liked the accused officers, he would be lenient in his judgment. Yet when it came to handing out the sentence, he was harsh because he wanted to please Bhutto.

Appointing Zia as Chief of Army Staff was not the only mistake Bhutto made. Instead of depoliticising a demoralised army which had surrendered to the Indian Army in East Pakistan, he opened a political wing in the ISI and used the army against the people in Balochistan, after dismissing the elected provincial government.

Bhutto annoyed the US administration by launching the project for making the atomic bomb. When American pressure increased in December 1976, he wrote a lengthy article that was published in Pakistan and the US, explaining that his foreign policies were based on bilateralism. In this article, which also included Foreign Office documents, Bhutto emphasised that he was the architect of the relationship with the Soviet Union and China. Although this was the right policy initiative, the American government did not like it for obvious reasons. After reading the article, I told a senior colleague that what Bhutto didn’t realise was that Pakistan wasn’t India and he wasn’t Nehru.

So while the US government was looking for an opportunity to destabilise Bhutto, nine political parties of the opposition collectively formed the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and launched a movement against Bhutto after the 1977 general election. The opposition claimed that 36 constituencies had been rigged and re-elections were required in these. Bhutto should have agreed to re-elections, instead of allowing the opposition to launch a countrywide movement against him. The right-wing parties converted a democratic rights struggle into a movement for the implementation of Nizam-e-Mustafa. Television news producers in Pakistan were instructed that no matter what the opposition leaders said, it should be reported that they were demanding the implementation of Nizam-e-Mustafa and the bringing down of prices to the levels of 1970. Zia had planted one Rafiq Bajwa as the secretary-general of the PNA and he was to help in hijacking the movement.

Bhutto called in the army to crush the movement — a fatal blunder on his part. By April 1977, as young reporters covering the political scenario, some of us started to get the feeling that the army was building a case against Bhutto, and was not really supporting him. I recall a young military officer, in charge of suppressing protests in some areas of Karachi, telling me that he was perplexed by the policies of his superior, who ordered the release of protestors as soon as they were arrested. In Karachi, I witnessed an interesting incident. The army and the police had blocked protestors from entering the Sindh Assembly. An army contingent was present, but it had asked Bhutto’s notorious Federal Security Force (FSF) to fire directly on the procession in one of the lanes on Burnes Road. Two young protestors were killed. While exchanging notes with other journalists at the Karachi Press Club, we felt the army was deliberately trying to foment hatred against Bhutto by using his shadowy FSF against the people.

After the coup, Mufti Mahmood and Professor Ghafoor told us that Bhutto and the PNA had almost reached an agreement for re-elections on some disputed seats, but their colleagues, who were close to the army, told them not to sign the agreement as Bhutto was going to be removed very soon. They needed everyone to delay the signing of the agreement by a couple of days.

Bhutto had come to power with the support of the army, which had asked him to take over as the majority leader after removing Yahya via a soft coup. It is often forgotten that Bhutto enjoyed a majority only in the Punjab and that he was not elected to rule the whole of Pakistan. He could only take over by pushing out East Pakistan, where the Awami League had the majority. In Balochistan and the NWFP, the majority was with the National Awami Party and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). In Sindh too, he was a few seats short of forming a government. After he was offered a government in Islamabad on a platter, he manoeuvred to lure two Sindh MPAs to form a government in the province as well.

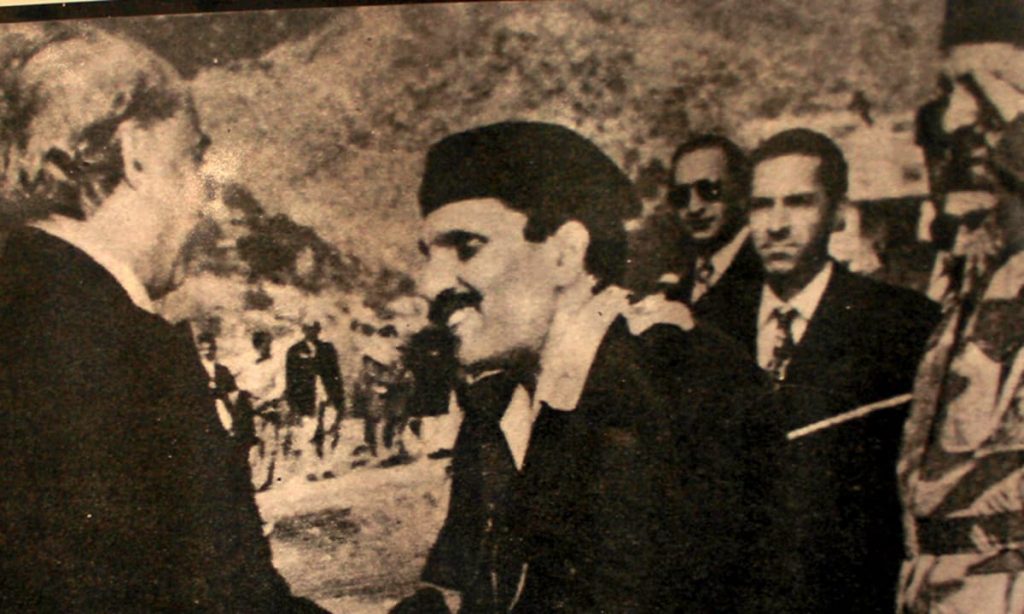

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto being escorted to the Lahore High Court for his trial in 1978.

In 1970, Bhutto had emerged as the leader in Punjab, mainly with the support of pro-China leftists. At his rally in Nishtar Park in Karachi, the main slogan was “The East is Red.” But by 1977, there was all right-wing Islamic sloganeering at the same venue. After five years of his rule, Bhutto drifted away from the left — his early support base — and started relying more on the zamindars and the bureaucracy. By the time Zia toppled him, he was already alienated from his core supporters.

Zia himself was killed by his own conspiring colleagues. Long before he was assassinated, there were visible signs that the establishment was not monolithic and that the US was not happy about his desire to instal an Islamist government in Afghanistan. He would not have survived for as long as 11 years had the clergy not taken over in Iran and had there not been an April Revolution in Afghanistan, in 1979.

Zia’s martial law regime carried out an Islamisation of the legal system, imposing, via the Nizam-i-Mustafa, draconian Islamic penal laws that entailed flogging and the amputation of the left hand. Shariat benches, established at the high court and Supreme Court levels in December 1978, could revise any law deemed un-Islamic. The offering of prayers during work hours was made compulsory in all government offices. By 1988, the Shariat Ordinance was promulgated. Under the misogynistic Hudood Ordinances of 1979, women got the short end of the stick. A woman who was raped could be convicted of adultery, while the Qisas and Diyat laws made it easier to get away with honour killings. Zia came down hard on press freedoms and newspapers such as the Daily Sadaqat and Daily Musawat were banned. The Eighth Amendment was also brought into effect, giving the dictator the power to dissolve the parliament under Article 58-2 (B). School curricula too, were altered to include an Islamic bias and student unions in universities were banned. The Qanun-i-Shahadat (Law of Evidence) Order of 1984, which repealed the Evidence Act of 1872, necessitated the testimony of two women against that of one man. Zia also introduced blasphemy laws through sections 295-B and 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code. These clauses particularly expanded the anti-Ahmadi laws.

Zia’s death in a plane crash, on August 17, 1988, marked the end of one of the darker periods in the country’s history. But his stint left its mark, in the form of madrassas, jihadis, the Kalashnikov culture and the general demodernisation of Pakistan.