Keeping it in the Family

By Mahir Ali | Cover Story | Published 7 years ago

Justin Trudeau

Pierre Trudeau

At a state dinner in Ottawa in 1972, visiting US President, Richard Nixon, raised a toast to his host’s four-month-old son: “The future prime minister of Canada, Justin Pierre Trudeau.” The “prophecy” was obviously intended as no more than a friendly gesture towards the proud new parents; when the augury was fulfilled in 2015, it was the first time Canada had a prime minister whose father had held the same post. What’s more, the gap between Pierre Trudeau’s prime ministership and that of his eldest son was more than 30 years.

There are many other countries where party leadership, and sometimes power, passes seamlessly down the family line. That is obviously the norm in absolute monarchies such as Saudi Arabia (the only country in the world to be actually named after its ruling clan) and the Gulf kingdoms, routine in some dictatorships, but also common in a surprising number of democracies, half-baked or otherwise.

If these instances could be described as variations on the monarchical form minus the regal titles, it could also be argued that there are feudal undertones — often overtones, in fact — to the close association between particular families and leading political parties across South Asia.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the world’s first female prime minister not long after her husband, Solomon, was assassinated by a Buddhist monk in 1959, and remained a fixture on the political scene in Ceylon/Sri Lanka thereafter. Her third term as prime minister — during which her daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga, was the president — ended just months before she died in 2000. Control of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party eventually passed from her family’s hands into those of the Rajapaksa brothers — but, luckily for the nation, they were not able to consolidate it.

In India, the Nehru-Gandhi lineage remains paramount in guiding the fortunes of the Congress, even though other party stalwarts have held the post of prime minister. It is intriguing to wonder what the nation’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, would have made of this tradition — which, one could argue, properly began with his daughter, Indira Gandhi, who was not even a minister when Nehru died in 1964, yet within two years she had succeeded him as the head of government — notwithstanding a number of rival (and considerably more senior) aspirants to the post. She groomed her younger son, Sanjay, as a successor, and when he died in a plane crash, she turned to her other son, Rajiv, a commercial airline pilot who apparently would rather have remained in the cockpit.

In India, the Nehru-Gandhi lineage remains paramount in guiding the fortunes of the Congress, even though other party stalwarts have held the post of prime minister. It is intriguing to wonder what the nation’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, would have made of this tradition — which, one could argue, properly began with his daughter, Indira Gandhi, who was not even a minister when Nehru died in 1964, yet within two years she had succeeded him as the head of government — notwithstanding a number of rival (and considerably more senior) aspirants to the post. She groomed her younger son, Sanjay, as a successor, and when he died in a plane crash, she turned to her other son, Rajiv, a commercial airline pilot who apparently would rather have remained in the cockpit.

He was propelled to the top when his mother was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in 1984 — and may well have returned to the PM’s post had he not been blown up by a Sri Lankan Tamil suicide bomber in 1991. The Congress then turned to his Italian-born wife, Sonia, who eventually succumbed to the pressure but has generally preferred to remain low key. At the end of last year, the presidentship of the Congress passed into the hands of her son, Rahul — the great-great grandson of early 20th-century Congress stalwart Motilal Nehru — who is now seen by some as the man most likely to halt Narendra Modi’s Hindutva juggernaut. For the moment, one is inclined to rate his chances at around the same level as those of Bilawal Bhutto Zardari.

Neighbouring Bangladesh, meanwhile, stands out as a nation where for several decades now the top political posts of Prime Minister and Opposition Leader have alternated between a pair of women — the daughter of the father of the nation, Hasina Wajed, and the widow of a military dictator, Khaleda Zia. Their respective parties seem to be stranded in the family-association rut.

Neighbouring Bangladesh, meanwhile, stands out as a nation where for several decades now the top political posts of Prime Minister and Opposition Leader have alternated between a pair of women — the daughter of the father of the nation, Hasina Wajed, and the widow of a military dictator, Khaleda Zia. Their respective parties seem to be stranded in the family-association rut.

I ndia’s Congress, though, seems to exemplify in particular the tendency towards a family name covering up for failures or uncertainty in the sphere of a coherent political philosophy, viable policies or a record of vote-winning accomplishments. The phenomenon is, by no means, restricted to India or the Congress, of course, but the point is that all too often it represents a diminution of democracy, or at the very least a lack of political ideals or imagination.

ndia’s Congress, though, seems to exemplify in particular the tendency towards a family name covering up for failures or uncertainty in the sphere of a coherent political philosophy, viable policies or a record of vote-winning accomplishments. The phenomenon is, by no means, restricted to India or the Congress, of course, but the point is that all too often it represents a diminution of democracy, or at the very least a lack of political ideals or imagination.

That is certainly not to suggest that there ought to be some kind of law against children or other family members of party or national leaders aspiring to scale the same political heights. It is hardly uncommon for children to follow one or both their parents into the same vocation, and it is perfectly possible for political talent to extend down the genetic line. The problem arises when parties or posts are regarded as family fiefs and nepotism becomes a substitute for new ideas.

There are scores of examples one could cite from every continent of political dynasties in the era of democracy, but the circumstances differ from one country to another. Progeniture should not hold back genuine political talent from emerging, even if the family name contributes in some measure to their vote bank — the Canadian instance of Pierre and Justin Trudeau is a case in point.

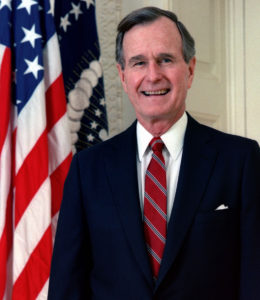

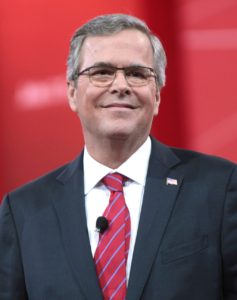

In the US, the Kennedys and the Bushes (the author Gore Vidal distinguished between the latter two by referring to George H.W. as Bush and George W. as Shrub) count among the more prominent family firms in the business of politics — although the incumbent present fully intends to bigly outdo them. But America may well have benefited from a second Kennedy presidency. And it is unlikely that Bush Sr’s one-term inadequacies were the mainspring behind the elevation to the White House of his son, who turned out to be a two-term disaster. Jeb Bush was at one point deemed the likeliest Republican nominee in 2016, but never came close, and the prospect of any sort of Clinton dynasty was destroyed by Hillary’s loss to the worst possible candidate anyone could have dreamed up, let alone drummed up.

In the US, the Kennedys and the Bushes (the author Gore Vidal distinguished between the latter two by referring to George H.W. as Bush and George W. as Shrub) count among the more prominent family firms in the business of politics — although the incumbent present fully intends to bigly outdo them. But America may well have benefited from a second Kennedy presidency. And it is unlikely that Bush Sr’s one-term inadequacies were the mainspring behind the elevation to the White House of his son, who turned out to be a two-term disaster. Jeb Bush was at one point deemed the likeliest Republican nominee in 2016, but never came close, and the prospect of any sort of Clinton dynasty was destroyed by Hillary’s loss to the worst possible candidate anyone could have dreamed up, let alone drummed up.

In faraway Kenya, meanwhile — the birthplace, Donald Trump long insisted, of his predecessor, Barack Obama — the two most prominent political personalities, Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, are the sons of their counterparts at the time of their nation’s independence almost 55 years ago. And in another example from the same continent, Joseph Kabila immediately succeeded his assassinated father, Laurent Kabila, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and has put off elections that he feared might unseat him.

In the Philippines, the Marcos and Aquino clans both remain active in politics, although only the latter succeeded in staking a claim to the presidency more than once. In Indonesia, the end of the Suharto dictatorship was followed shortly afterwards by the empowerment of his predecessor’s daughter, Megawati Sukarnoputri.

In the Philippines, the Marcos and Aquino clans both remain active in politics, although only the latter succeeded in staking a claim to the presidency more than once. In Indonesia, the end of the Suharto dictatorship was followed shortly afterwards by the empowerment of his predecessor’s daughter, Megawati Sukarnoputri.

In Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of the nation’s venerated independence leader, Aung San, put herself forward as a champion of human rights and democracy during her long years as a symbol of resistance to military dictatorship, but embraced the state’s ruthless repression of minorities as soon as she was allowed a foothold in the portals of power.

Elsewhere in the continent, in many of the Central Asian republics that have emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union, family dynasties are generally the rule, in most cases spawned by former Communist Party stalwarts. North Korea stands out, though, as the only country that still pays lip service to communism where the power structure is purely hereditary.

There are instances of the phenomenon in Latin America — the Perons in Argentina, the Freis in Chile and the crisis lately spawned in Nicaragua by a once progressive leader, Daniel Ortega, who is married to his vice-president and is often compared these days, including by supporters of the Sandinista revolution, to the Somozas, who ruled the nation with an iron fist for more than 40 years in the mid-20th century.

There are fewer examples of ruling dynasties to be found in Europe’s recent history, although that could change as its constituent nations turn rightwards, sometimes sharply. There was something ominous about the control of France’s fascistic National Front passing from Jean-Marie Le Pen to his daughter Marine; neither of them, thankfully, succeeded in their attempts to secure the Elysee Palace, but they came too close for comfort. Three generations of Papandreous, on the other hand, served as democratically elected prime ministers of Greece. Perhaps the most bizarre instance of family rule in an ostensibly democratic context was provided, though, in 2006-07 by Lech Kaczynski and Jaroslaw Kaczynski serving simultaneously as president and prime minister. They were not only brothers but identical twins — potentially capable of substituting for one another without very many people noticing.

General Aung San

Aung San Suu Kyii

Readers might have noticed that in many cases the supposed right of political inheritance — whether immediately invoked or substantially delayed — springs from assassinations. And claiming such inheritance occasionally entails dreadful consequences, as witnessed in India and Pakistan. But perhaps the most bizarre recent instance of political heredity gone awry occurred in South Korea, after Park Geun-hye was elected the country’s first female president. Her father, Park Chung-hee, ruthlessly exercised power during some of South Korea’s bleakest years, from 1961 until he was killed by his own intelligence chief in 1979.

Park Geun-hye was not really expected to answer for her father’s legacy some 35 years on (although she defended his coup). But she quickly established a rather more unusual one of her own involving a Christian cult, Viagra, influence-peddling and abuse of power. By the time she was impeached by the national assembly in 2016, her popularity rating had dwindled to low single digit figures. The constitutional court upheld it the following year, thereby removing her from office. On April 6 this year, she was sentenced to 24 years in jail.

There was no vendetta involved in her descent from the presidency to prison, merely a sense of repugnance. Sometimes, democracy indeed is the best revenge for an unearned sense of entitlement.

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.