Haunted by the Past

By I. A. Rehman | International News | Published 9 years ago

The recent deterioration in Pakistan’s relations with Bangladesh — the reciprocal expulsion of diplomats from one another’s capitals and the hardening of Bangladesh’s visa regime for Pakistani citizens, for example — should not have surprised anyone. The relationship between the two countries has been so tenuous all along that it cannot absorb even the slightest grievance caused by one side to the other.

The two countries are divided by history, and, more than that, by memories of historical events. The Pakistanis have not forgiven the people of Bangladesh for breaking away from the state they had jointly created no more than 68 years ago, although their feelings of hurt on this score are only fractionally as strong as the hurt felt by the Indians at the partition of their land. Likewise, Bangladeshis cannot forget what was done to them by Pakistan’s political and military bosses during 1970-71. The Pakistanis celebrate March 23 as their Republic Day; the Bangladeshis recall on that date, with anger and sorrow, the start of the military action against them in 1971. December 16 is celebrated by Bangladeshis as the day of their liberation, while the Pakistanis mourn (perhaps more strongly than the state’s break-up) the fall of Dhaka.

Many people in the world, such as the European states for instance, have been divided by more bitterly fought wars between them and suffered even heavier losses. But they have put aside the bitterness of the past decades and centuries to establish the European Union. Many Pakistanis, too, feel that Islamabad and Dhaka need to bury the past (although they do not apply the same logic to their relations with India). These people underplay two aspects of the 1970-71 conflict; first, that the Pakistani rulers had forced a war of national liberation on the Bengali Pakistanis, and, second, that they had systematically used rape of women as a means to beat off the challenge to their power.

What this, in effect, means is that the Pakistanis can get over the events of 1970-71 relatively more easily — because they have little attachment to their land and history has a nominal meaning for them — than the Bangladeshis, for whom history is a record of yesterday’s happenings. Obviously, both countries were (and are) required to take strong and positive steps to bridge the chasm that separates them. And perhaps Pakistan’s responsibility to move in this direction is greater than Bangladesh’s.

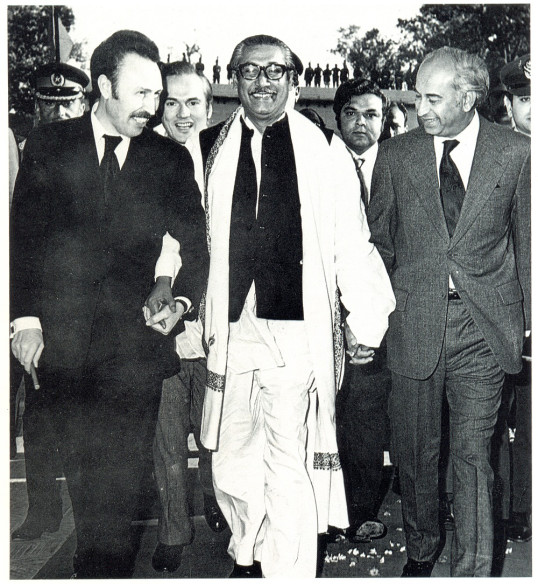

Bangladesh’s grievances against Pakistan did not end in 1971. It felt very strongly about trying the Pakistani state functionaries for war crimes but, due to big power pressure, was obliged to give up its demand and sign an accord to this effect. In 1974, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was persuaded, in the name of religious solidarity, to travel to Lahore and attend the Islamic summit. He badly needed help to build the new state and hoped to gain considerably from a division of Pakistan’s pre-1971 assets. He welcomed Pakistan’s then prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, to Dhaka with open arms but the promises made with regard to the release of Bangladesh’s share of assets were quickly forgotten. This, by a state that still excuses India of not playing fair vis-Ã -vis the division of assets in 1947.

The absence of a settlement on the fate of the Biharis who opted for Pakistan in 1971-72, has also soured Pakistan-Bangladesh relations. General Zia created a legal bar to the repatriation of these Biharis to Pakistan and subsequent plans to carry out repatriation with funds provided by Muslim states have been wrecked by lack of faith on all sides.

The confrontation between the Awami League of Sheikh Hasina Wajid and the National Party of Khaleda Zia has also affected Pakistan-Bangladesh relations. Most people in Bangladesh think that Pakistan has a soft corner for the BNP partly because the party has its roots in the military officers’ political ambitions and, more than that, because it has advanced the concept of the Bangladeshi Muslim identity as against the Awami League’s preference for the historically-sustained Bengali identity. There have been occasions when responsible persons in Bangladesh have not stopped short of accusing Pakistan of interfering in their internal affairs. That these charges are denied by Pakistan does not mitigate the Bangladeshi people’s anger because the word of the state in South Asia enjoys little credibility.

Unfortunately, Bangladesh’s success in building up its economy, surpassing Pakistan in several social sectors and securing its place in the councils of the world, has not proved sufficient to appease its nationalist fervour. The level of confrontation between the two woman-led parties and their lack of tolerance for one another has, perhaps, no parallel in the world. They make impossible demands on state institutions and the civil society to be bonded slaves to one or the other.

Unfortunately, Bangladesh’s success in building up its economy, surpassing Pakistan in several social sectors and securing its place in the councils of the world, has not proved sufficient to appease its nationalist fervour. The level of confrontation between the two woman-led parties and their lack of tolerance for one another has, perhaps, no parallel in the world. They make impossible demands on state institutions and the civil society to be bonded slaves to one or the other.

Further, the present Bangladesh government has lost considerable goodwill in the world by pursuing the so-called war crime trials with a determination worthy of a noble cause, especially in view of its deviation from the universally-acclaimed Mandela doctrine of reconciliation. Pakistan defied the demand of prudence by berating Dhaka for executing some of its citizens. The criticism might not have been entirely invalid, but Pakistan was hardly qualified to censure any country for hanging people in view of its own dark record in this matter, even if the world were to forget 1970-71.

Unfortunately, the bitterness between Pakistan and Bangladesh has not been confined to inter-state relations; it has seeped to the level of relations between their peoples. Some in Pakistan deemed it necessary to denounce their compatriots who were honoured by the Bangladesh government for their opposition to the 1971 military operation in East Bengal. And there are many people in Bangladesh who refuse to talk to Pakistanis. In Faiz’s words, how many rainy seasons will it take before the stains of blood spilled 40 years ago begin to fade?

Some people in both Pakistan and Bangladesh, no doubt out of despair, want the two countries to develop mutual friendship around the religious bond. They choose to ignore the verdict of history that religion failed to keep unity between Arabs and Arabs, between Arabs and Berbers, between Arabs and Turks, between Ottomans and Iranians, and between Afghans and Mughals, and history bears testimony to the fact that more Muslims have been killed by fellow Muslims than by any non-Muslim power.

Both Bangladesh and Pakistan are only hurting themselves by living in the past. Even if there is no possibility of them making any mutual gains by burying the hatchet, they must realise the cost of living with rancour towards each other. Feelings of anger and hate only undermine any people’s capacity to distinguish between right and wrong.

Indeed, both Pakistan and Bangladesh have to realise their duty to their respective populations and to the collective interests of the South Asian fraternity. Along with other South Asian countries, they must learn to go by their common interests and not by their past differences. It appears that these two countries are not mature enough to resolve their differences bilaterally. However, the South Asian regional cover offers them possibilities of realising themselves severally as well as collectively. The choice of this path demands statesmanship of the highest order, but the target is not unattainable. A beginning towards normalisation of Pakistan-Bangladesh relations can be made by promoting free travel between the two countries. Greater contacts between ordinary citizens of the two countries will help them to know and respect each other.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s March 2016 issue.

Mr. I.A. Rehman is a writer and activist living in Pakistan. He is the secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan Secretariat.