Aspiring to be Jinnah

By Yasser Latif Hamdani | Special Report | Published 8 years ago

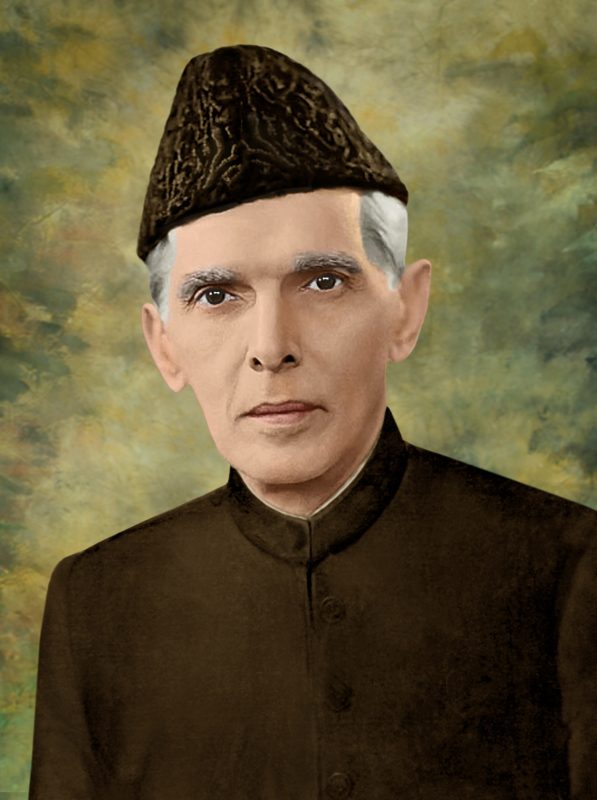

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father of the country, is the gold standard for Pakistani politicians, despite the fact that the principles he stood for are absent in the current politics of the country. A self-made man, rising from a middle class family in Karachi, Jinnah’s twin passions were law and politics. Before discussing Jinnah’s relevance in modern Pakistan, it is necessary to take a bird’s eye view of his political career. Vicissitudes of time and politics led this once Congressman and best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity to become the apostle of Muslim nationalism and the virtual dictator of the All-India Muslim League. The journey that he took from Jinnah the parliamentarian in Indian’s central legislature, to become Pakistan’s all powerful governor general and president of the Constituent Assembly, has been the subject of much discussion among historians. However, more often than not, aspirants to his mantle have attempted to emulate him without taking into account the unique circumstances of this journey.

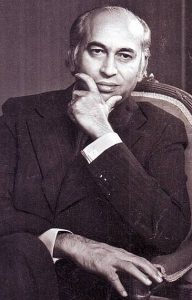

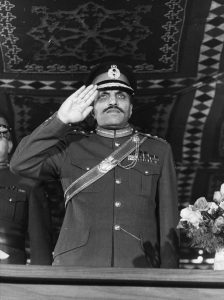

Since 1971, after Pakistan broke into two, there was a deliberate attempt by all leaders who came to power, to seek legitimacy by appropriating Jinnah. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto fashioned himself as Quaid-i-Awam, after Jinnah’s title Quaid-i-Azam. General Zia-ul-Haq attempted to appropriate Jinnah by first Islamising him — endeavouring to transform the Anglicised lawyer into an Islamic apostle. Forced by the people into allowing party politics at long last, Zia made his own faction of the Muslim League, in which Muhammad Khan Junejo, Elahi Bux Soomro and Nawaz Sharif — gentlemen who had nothing to do with the historic Muslim League — were leading members. Indeed, Elahi Bux Soomro’s uncle, the late Allah Bux Soomro and father, Maula Bux Soomro, were strident opponents of the Muslim League in the pre-partition era.

Since 1971, after Pakistan broke into two, there was a deliberate attempt by all leaders who came to power, to seek legitimacy by appropriating Jinnah. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto fashioned himself as Quaid-i-Awam, after Jinnah’s title Quaid-i-Azam. General Zia-ul-Haq attempted to appropriate Jinnah by first Islamising him — endeavouring to transform the Anglicised lawyer into an Islamic apostle. Forced by the people into allowing party politics at long last, Zia made his own faction of the Muslim League, in which Muhammad Khan Junejo, Elahi Bux Soomro and Nawaz Sharif — gentlemen who had nothing to do with the historic Muslim League — were leading members. Indeed, Elahi Bux Soomro’s uncle, the late Allah Bux Soomro and father, Maula Bux Soomro, were strident opponents of the Muslim League in the pre-partition era.

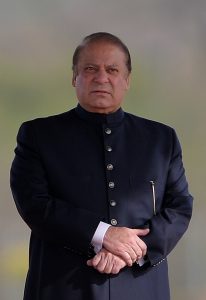

Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto did a commendable job in reversing the Islamisation of Jinnah to some extent, but was not wholly able to overcome the national narrative set by Zia. General (R) Pervez Musharraf laid claim to Jinnah’s mantle in justification for his enlightened moderation. He also fashioned a faction of the Muslim League after Jinnah, called the Muslim League Quaid-i-Azam. Imran Khan’s supporters are convinced that the cricketer-turned-politician is Jinnah reborn. Nawaz Sharif’s supporters see him as the legitimate heir to Quaid-i-Azam and claim for PML-N, the status of the founding party of Pakistan. Like Napoleon III, the mid-19th century French president and emperor, who aspired to be like Napoleon Bonaparte, Pakistan is full of aspirants aiming to be ‘Quaid-i-Azam Saani.’ None of them have quite gotten there.

What is more is that they have drawn all the wrong lessons from the Quaid. Jinnah, in the heyday of his leadership during the Pakistan Movement, was the embodiment of power. His word was often the last in the Muslim League. He owed this position to persistent hard work, which saw him climb up the totem pole ahead of the Knights, Nawabs, Sardars and Khan Bahadurs. Despite his unquestionable authority, Jinnah was a patient listener who would allow all of his colleagues to speak before arriving at a decision on an issue. It is important to underscore that Jinnah had acquired this authority through a morally unimpeachable character. There were no skeletons in the closet, no allegations of financial corruption and no scandals. Thus, when Jinnah ordered, others followed. Pakistan’s politicians who have followed Jinnah have sought to emulate him by becoming virtual dictators of their parties, but have done so without the corresponding credentials of incorruptibility and integrity.

What is more is that they have drawn all the wrong lessons from the Quaid. Jinnah, in the heyday of his leadership during the Pakistan Movement, was the embodiment of power. His word was often the last in the Muslim League. He owed this position to persistent hard work, which saw him climb up the totem pole ahead of the Knights, Nawabs, Sardars and Khan Bahadurs. Despite his unquestionable authority, Jinnah was a patient listener who would allow all of his colleagues to speak before arriving at a decision on an issue. It is important to underscore that Jinnah had acquired this authority through a morally unimpeachable character. There were no skeletons in the closet, no allegations of financial corruption and no scandals. Thus, when Jinnah ordered, others followed. Pakistan’s politicians who have followed Jinnah have sought to emulate him by becoming virtual dictators of their parties, but have done so without the corresponding credentials of incorruptibility and integrity.

Bhutto, who invoked Jinnah’s memory in the 1970s, was drawn from the wealthy feudal elite of Sindh, his protestations of socialism notwithstanding. Bhutto was defined by his social and material conditions as a scion of Sindh’s landed aristocracy. While Berkeley, Oxford and Lincoln’s Inn had given him a certain amount of cosmopolitan polish, at heart he remained a wadera from Sindh and that defined his politics, even after he became the prime minister of Pakistan. His treatment of his political opponents and his own party members is well known. His politics too was a marked contrast to Jinnah’s political style. There were certain lines that Jinnah would just not cross as a popular leader. During the Pakistan Movement, his opponents in Majlis-i-Ahrar and Jamiat-i-Ulema Hind, as well as a section of conservative Muslims within his own party, attempted to pressure him into turning out the Ahmadis from the Muslim League. Jinnah refused. He instead declared that he could not declare anyone who professed to be a Muslim to be a non-Muslim. He did not give in to the blackmail of the religious parties arrayed against him. He refused to entertain any resolution that would commit future Pakistan to an exclusively Islamic polity in the Muslim League. Bhutto, the strongest prime minister in the country’s history, barring Nawaz Sharif’s second tenure, sheepishly acceded to the same long standing demand by religious parties and declared Ahmadis non-Muslims through the second amendment to the Constitution. Prime Minister Bhutto also agreed to make Islam the state religion of Pakistan, thereby vitiating the spirit of what Jinnah had promised so eloquently to the non-Muslims of Pakistan, on August 11, 1947. Bhutto, therefore, was no Jinnah. He was not made of the stuff that could withstand popular pressure.

Nawaz Sharif — elected thrice to the office of prime minister — has repeatedly been outmanoeuvred by  his political opponents. In his case, the problem has always been integrity. Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion. In public perception, Nawaz Sharif, unfortunately, has always been suspect. The comparison with Jinnah, therefore, cannot hold. Jinnah was not suspected of financial corruption by anyone. Even though he was a rich man and the owner of luxurious properties all over the subcontinent, not a single one of his detractors accused him of any financial wrongdoing. Jinnah was meticulous about his paperwork and always made sure there was nothing in his record that could tarnish his credibility or integrity. It was a conscious choice. A leader must lead by example. Nawaz Sharif has taken the opposite route.

his political opponents. In his case, the problem has always been integrity. Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion. In public perception, Nawaz Sharif, unfortunately, has always been suspect. The comparison with Jinnah, therefore, cannot hold. Jinnah was not suspected of financial corruption by anyone. Even though he was a rich man and the owner of luxurious properties all over the subcontinent, not a single one of his detractors accused him of any financial wrongdoing. Jinnah was meticulous about his paperwork and always made sure there was nothing in his record that could tarnish his credibility or integrity. It was a conscious choice. A leader must lead by example. Nawaz Sharif has taken the opposite route.

Imran Khan, another claimant to Jinnah’s mantle, is said to be honest, but lacks in political foresight, if not in fortitude. Whereas Jinnah would take his time in assessing a situation and would, in his own words, think a hundred times before uttering a single statement, Khan is impetuous and suffers from foot in the mouth disease. Consequently, he often takes public positions only to abandon them at a later date, earning him the sobriquet, “U-Turn Khan.” Khan, despite his time spent in the West, often panders to the religious right. Despite protestations that he stands for the equality of women and minorities, he has often let them down by meekly surrendering to the Jamaat-i-Islami, his allies in government. Those who know Imran Khan, say that his highly superstitious nature often finds its way into his politics. This is a far cry from Jinnah, who had little time for otherworldly obsessions and who was often flabbergasted by Gandhi’s spirituality. Khan, therefore, also fails in his quest to be the next Jinnah.

Must there be another Jinnah? That the country needs politicians of integrity and probity, goes without saying. Pakistan also needs men and women who believe in the rule of law and who share Jinnah’s vision for an inclusive Pakistan for all. Yet, perhaps Pakistan’s democracy no longer requires a towering, monolithic figure. After all, the business of the independence struggle and the creation of a new country is very different from the job of running it. There can only be one Jinnah, as his circumstances were unique. Grey Wolf: The Life of Kemal Ataturk, by Harold Armstrong and Emil Lengyel, was a book that Jinnah loved. It ends with the following lines on Ataturk: “He is Dictator in order that it may be impossible ever again that there should be in Turkey a Dictator.”