New Directions

By Niilofur Farrukh | Special Report | Published 8 years ago

Zubeida Agha

Art movements in Pakistan in the last 70 years have been nebulous, often sans manifesto and usually short-lived. These energy-intensive initiatives are collective responses to stimuli, may they be political or social. These ‘subaltern’ movements have privileged local priorities and embedded them in the cultural DNA to transform the art of Pakistan.

Art movements are defined as a tendency or style in art with a specific common philosophy or goal followed by a group of people for a restricted period of time. Modernism has been the most influential movement in Pakistan that saw Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Art adopted by young artists while looking for a new language.

Francis Newton Souza on a visit to Ali Imam, once shared with me that his participation in the protest rallies with the advocates of freedom in Mumbai in the 1940s, cost him his coveted seat at J J School of Art, but it also gave him the opportunity to establish Progressive Artists. Inspired by this, the Lahore Art Circle was founded a few years later. Both these movements were motivated by a pressing need to transition from traditionalism to new ideas of the time. Attracted by the experimental structure and independent values of modernist philosophies, the artist grasped its immense possibilities. The Lahore Art Circle had the advantage of taking root in a city where Amrita Sher Gill had left behind an influential legacy of an avant-garde art practice. In these individual and collective initiatives can be traced the genesis of Modern Art in Pakistan.

Gulgee

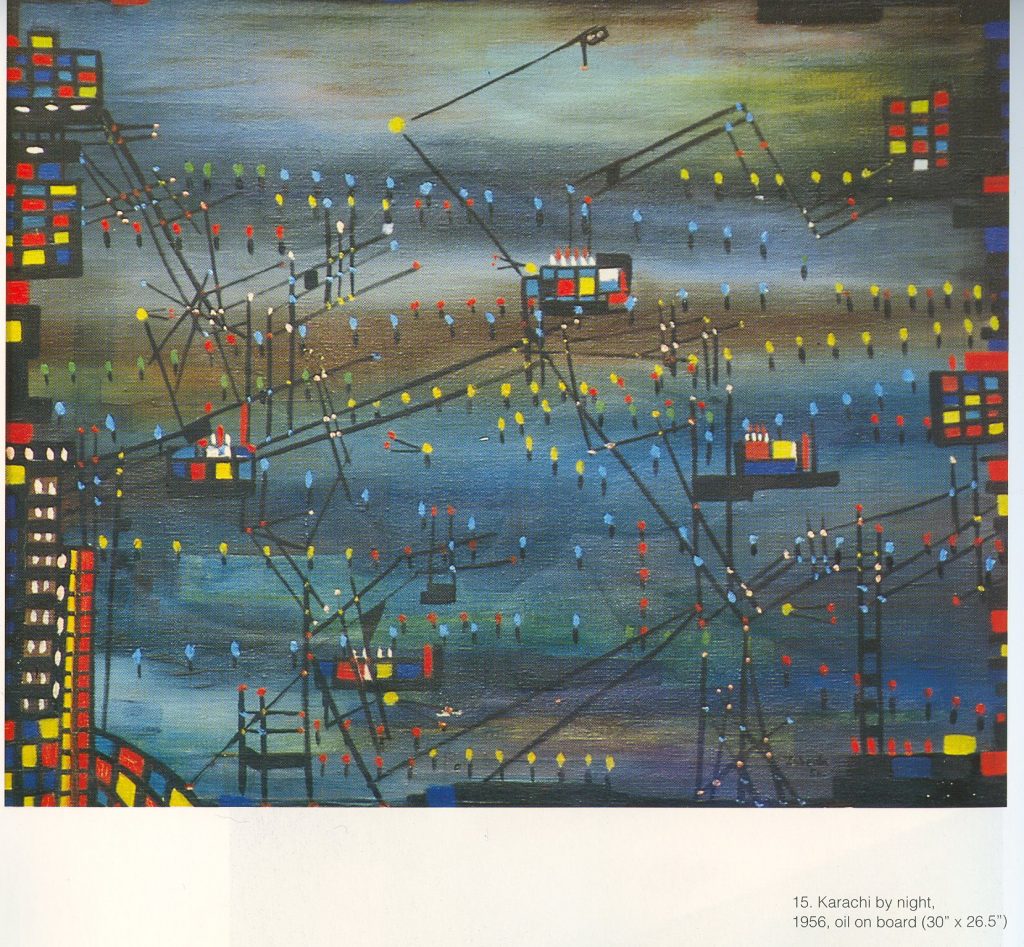

Zubeida Agha took the lead when she held Pakistan’s first show of Modern Art. Taught by a student of Picasso, who was interned in Lahore during WWII, Agha began her journey with confidence. Ali Imam, after a stint in London’s art academies, and Shakir Ali, who was mentored in Paris and Prague, on their return joined Agha, as influential proponents of Modern Art. In Pakistan, early Modernism surfaced under the heavy influence of Cubism. This derivation gave way, within a decade, to bold experiments from the studios of Bashir Mirza, Gulgee, Lubna Agha and Zahoorul Akhlaq, among others. The Art of late Pakistani Modernism of the 1970s gives credence to Rasheed Araeen’s discourse on ‘multiple modernities’ that unpacks the myth of Modernism solely as a Euro-American enterprise. Modernism in non-western locations often morphed into a distinct expression anchored in its context which at best, had only had a weak resonance of Modern Art created in Western art capitals.

The first woman artist to unabashedly bring her body and women’s issues into her art was Nahid Raza in the 1970s. Later, more voices joined into an inter-generational Womens’ Art Movement. The commitment to this movement got impetus from Zia-ul-Haq’s persecution of women; the forced shrouding and their marginalisation as lesser citizens drew a response on the street and in the studio. References to the politics of sexuality in young Mariam Agha’s 2017 oeuvre recalls Nahid paintings from earlier decades. This is a testament to a movement that may have seen both active and dormant periods, mutations and overlaps, but remains relevant and persistent.

Nagori

Protest Art was founded with the energies of dissent during Pakistan’s most repressive dictatorship under General Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s. Salima Hashmi, Nagori, Jamal Shah and Anwer Saeed led this movement against draconian policies. Artists became a part of the countrywide people’s movement against human rights abuse. In an interview for Nukta, Jamal Shah shared, “Prior to this our art had been seeking conformity with the West. Now for the first time, artists began to ask questions and address social issues around them. This was the first time the artist connected to the concerns of the public.” This movement echoed the voice of imprisoned poets and writers against daily brutalities and the bigotry of state-driven Islamisation. The movement faced bans and was heavily censored by state institutions till democracy was restored.

Under democracy in the 1990s, the heightened awareness of the rights of the man-on-the-street took on the avatar of Popular Art. Its connection with ‘low brow’ subjects and bazar sensibilities introduced unexplored street iconography and concerns. Durriya Kazi, David Alesworth, Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi were its pioneers, later joined by Huma Mulji, Asma Mundrawala and Bani Abedi. This movement marks a moment in Pakistan’s history when social forces, regardless of class, converged to find common ground. The revival of ZAB’s ‘awamisation,’ a growing grassroots representation in politics and cultural patronage by the democratic government, created an environment conducive to a wider dialogue.

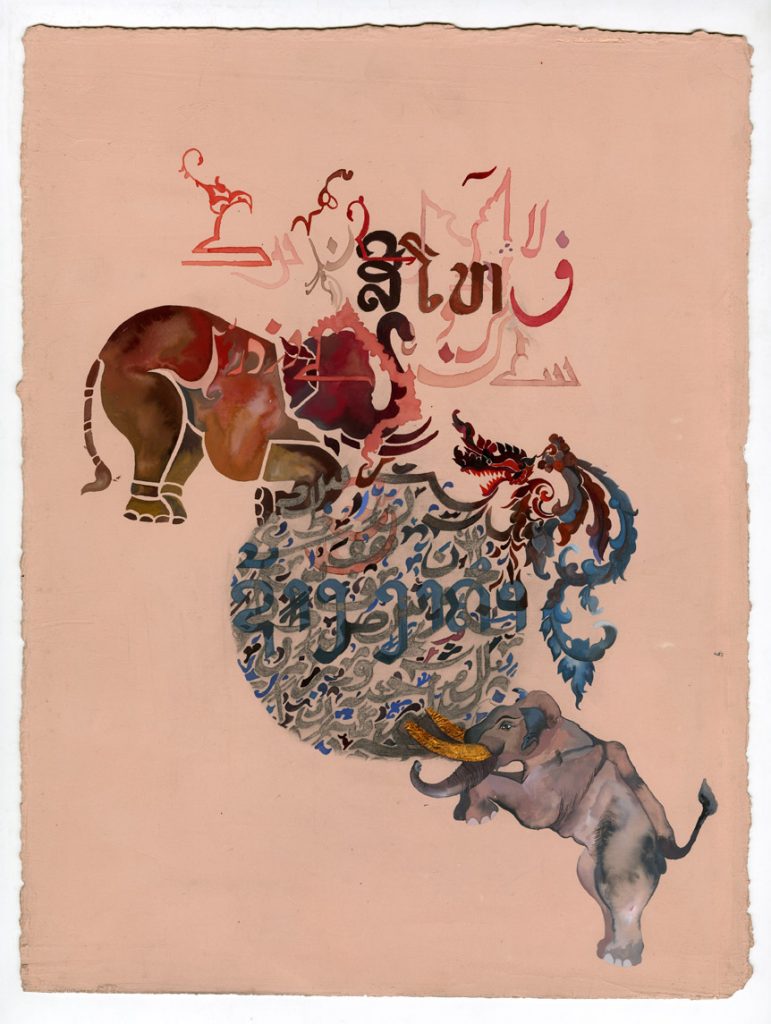

Bani Abedi

The 1990s also saw Zahoorul Akhlaq return to head the Fine Arts Department at National College of the Arts (NCA), where he began a dialogue on new ways of ‘seeing’ the context. The employment of critical tools to deconstruct received knowledge was central to his pedagogy that midwifed the Neo-Miniature Movement. Through Shahzia Sikander, it received an early exposure in the US where it began to be hailed as Pakistan’s first home-grown art movement. By early 2000 this grew stronger, with well-entrenched roots in the Miniature Painting Department of the NCA. Two landmark curatorial projects can help us to understand its discursive possibilities beyond history and technique. Karkhana, conceptualised by Imran Qureshi with a group of his peers living in Pakistan and abroad, was a project that explored the tradition of the collaborative practice of Miniature Painting.

The project successfully married experiment and its purist practice on a single vasli. Beyond the Page, a show curated by Hammad Nasser, a decade later, was premised on miniature painting being a sensibility that also informed the art of non-miniaturists. These multiple readings have been crucial in extending the discourse on the Neo-miniature Movement.

Imran Qureshi

Pakistani artists have responded to wars, state violence and terrorism in the post 9/11 scenario from a multiplicity of vantage points. Soon after the first US-led bombing of Afghan territories, Risham Syed’s work, with an infant’s tunic delicately embroidered with guns and bombs, drew attention to the forgotten child victims. David Alesworth’s critical commentary on the air-dropped food packages in areas under prolonged bombing and siege brought into discussion the propaganda war versus killing fields in a conflict. Pakistani artists living at home and abroad have joined the movement to discuss the complexity of the narrative of terrorism. Amin Rehman, based in Canada, challenges media headlines and slogans in his text-based practice. His recent collaboration with Tariq Ali interprets his polemic writings through an artist’s lens. Imran Qureshi’s site- specific work in a Sharjah courtyard and on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York, in the fields of UK, and in Australia have been a forceful recollection of bloodshed in asymmetric wars that recognise no boundaries.

On city streets where the architecture of security barriers, roadblocks and barbed wire has divided people with fear and anxiety, artists have stepped forward to reclaim public spaces and bring the fractured cities back through Public Art. The painting of wall murals in many parts of Karachi was an inclusive gesture that covered hate slogans with images that celebrated life for diverse communities. Awami Collective in Lahore has mobilised inner city dwellers and brought thousands of citizens together in a show of solidarity. The ‘Reel on Hai’ project of the Karachi Biennale has invited dozens of artists to recycle giant cable reels into artworks displayed in parks, hospitals, educational institutions etc to provoke dialogue and public interface with art. Anti-Art University looks at land issues and politics of displacement and uncontrolled development in Karachi while highlighting forgotten indigenous histories.

Shahzia Sikander

Like most Art Movements of the ‘South,’ collective trajectories in Pakistan have been driven by the acceleration of changes. Art that was previously driven by academic debates was instrumentalised to counter the fallout of power abuse in post-colonial struggling democracies. These movements, often in confrontation with the State, instead of being a part of the official narrative, find space in public memory.

Art historians with a fixed notion of art movements often look for manifestos, underpinning theories and a formal membership to validate these organic collective responses.These movements are built on a different engagement that connects to the pulse of the people, their fears and their hardship. They are the Subaltern Art Movements that need a new chapter in the world’s postcolonial history. They grow out of a moment and, after running their course, seamlessly transform while leaving behind residues that cannot be erased from the people’s memory.

Art critic Niilofur Farrukh contributes a monthly column on art-related issues.