A Living History

By Deneb Sumbul | Special Report | Published 8 years ago

Even before she was born, on February 23, 1931, in Bhopal, her eminent grandfather, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar had already chosen a name for her. Suffering from multiple illnesses the Maulana had expressed a wish to his youngest daughter, Gulnar, that if her firstborn was a girl, she should name her Aziz Fatima. And so she did.

Now 86, Aziz Fatima enjoys her chilli chips, samosas and coffee, as she shares memories of her family, and specifically of Maulana Jauhar, whom she describes as a lion among men. “My grandfather was a firebrand revolutionary, and he used his talents as an exceptional writer and orator to defy the British Raj and enlighten Indians on how they were losing their identity and culture under colonial rule. His words would be so brilliant, that I believe even the Viceroy would read his newspaper, The Comrade, and his articles. You kids were not around at that time, when we had to salute the Union Jack in cinemas, schools and everywhere else. Now we all salute the Pakistani flag and that is the difference.”

Aziz’s interview to the Newsline is rich in historical anecdotes of her family, the focal point being Maulana Jauhar, the legendary pre-Partition Muslim leader who demanded the right of self-determination for Indians. But her family’s struggle against the British rule precedes the Maulana, and can be traced back to the first War of Independence in 1857 – otherwise known to the British as the Sepoy Mutiny.

Aziz takes us through a fascinating journey that includes her other dynamic family members who were active in the freedom movement, including her grandmother Amjadi Bano (Maulana’s wife), Shaukat Ali (Maulana;s brother), her own father Shuaib Qureshi and the driving force behind them all, Abadi Begum, the Maulana’s mother [Aziz’s great-grandmother].

Aziz Fatima Kazi: Granddaugher of Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar was 15 at the time of Partition.

Aziz begins her family history with Maulana Jauhar’s maternal grandfather, Sheikh Muzafar Ali of Central Asian descent, who settled in the small town of Najibabad in Uttar Pradesh. A cavalry soldier with the local king, Sheikh Muzafar Ali and his extended family participated in the 1857 uprising against the British. According to Aziz, as part of the reprisals, the British slaughtered more than 250 members of his extended family and had their heads put on display on Delhi’s ‘Khooni Darwaza.’

Sheikh Muzafar Ali had sent his wife and two children, Abadi and Rashid, to Rampur state to take refuge. The British would not attack that state because the Nawab of Rampur had sworn allegiance to them. Meanwhile, Sheikh Muzafar Ali sustained injuries while escaping and hid in a cave from where he was later retrieved half-dead. He rejoined his family in Rampur but remained incognito due to the Nawab’s outward allegiance to the British; he could not be seen to be giving refuge to ‘traitors.’ At the time, his daughter Abadi Begum, who was to become a powerhouse in the family, was only five years old.

Abadi Begum was married to Abdul Ali Khan, a close childhood friend of the heir apparent of Rampur. The couple had five sons and a daughter, and the youngest two were named Shaukat Ali and Mohammad Ali [Jauhar]. Unfortunately, Abdul Ali Khan died of cholera, but Aziz discloses that there were strong rumours he had been poisoned along with the heir apparent. The Maulana was then merely five years old.

The brutality with which the British had killed so many of her flesh and blood was etched in Abadi Begum’s memory, as was the injustice meted out to the last Mughal Emperor, who was treated as a traitor in his own country and three of his sons were executed. Abadi Begum became a driving force in her family and instilled in her sons the need to rid India of the British. She felt the only way to defeat them without a single act of violence was by learning their language and customs and beating them at their own game. She is believed to have said, “I want the Union Jack off the Red Fort and I want our own flag flying there,” says Aziz.

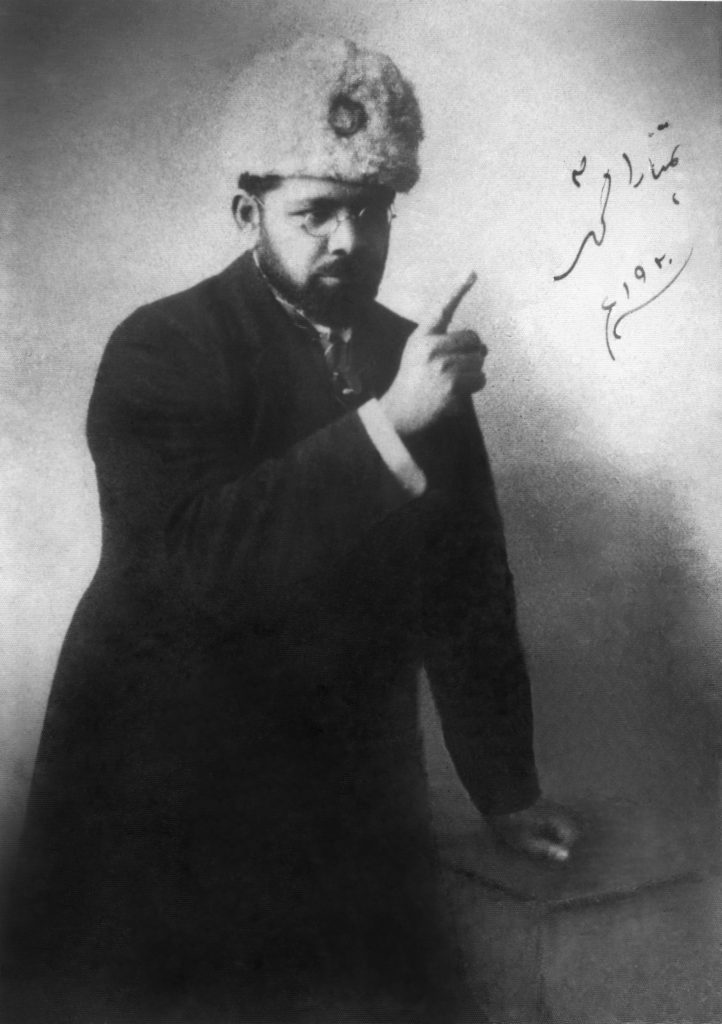

Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar in 1920.

Determined that her sons master the English language, Abadi Begum, lovingly called ‘Bi Amma,’ sought permission from her in-laws to admit them in English-medium schools. They refused, saying it had never been done before. Undeterred, Bi Amma sold her jewellery to raise the money. Seeing her resolve, her in-laws not only bought back her jewels but paid for all her sons to be educated in Aligarh Muslim School and University. “An outstanding student, my grandfather exhibited his brilliance there early. The family then decided to pool their finances to send him to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he studied Modern History and passed with distinction. He failed his ICS exams, however, as he was not very inclined towards it at the time.”

The Maulana married his first cousin, Amjadi Bano Begum, in 1902 and settled down while serving, first as Principal of the Rampur State High School, and later as Chief Education Officer of the state, introducing reforms in the education system. Later, he joined the Baroda civil service. But he was increasingly drawn towards activism and Indian politics. Perhaps the turning point in his life came in 1906, when he drafted the All-India Muslim League (AIML) manifesto called the Green Book. Aziz still possesses a copy of what was presented at the first AIML meeting in Dacca (Dhaka), in which many of the Maulana’s proposals were accepted. “From that point onward, he was considered one of the founding members of AIML,” says Aziz.

The following year, he described the prevailing atmosphere and events in a series of articles for the Times of India called, ‘Some Thoughts on the Present Discontent’ which was later published as a book. His articles also appeared in major British newspapers like The Times, The Manchester Guardian and The Observer. In 1911, he decided to pack his belongings and, along with the family, leave for Calcutta (Kolkata) — then the capital and the hub of political activity. There he established The Comrade, a weekly English newspaper which toed the AIML party line in India and abroad, and propagated the concept of self-rule. Aziz narrates, “Once, while in the visitor’s gallery of the Assembly, politicians sitting below asked the Maulana to join them and he quipped, ‘Gentlemen, I prefer to look down on you.’”

When the capital was moved from Kolkata to Delhi, he shifted The Comrade to the new capital and from there, launched Hamdard, an Urdu-language daily newspaper, in 1913. For his poetry, he chose Jauhar as his nom de plume and the title of ‘Maulana’ was given to him as a mark of respect.

Since the British Empire was at war with the Ottoman Empire, Indian Muslims could not fight on the side of the Turks during the Balkan wars. In 1912 the Maulana arranged for a medical mission comprising about 50 volunteers to be sent to Turkey as medics under Dr. M. A. Ansari. Shuaib Qureshi, who would later become his son-in-law (and Aziz’s father), was also part of the mission. It was then that the Maulana started growing a beard, wearing a cloak and a hat with a crescent on it and joined Maulana Abdul Bari Farangi Mahali’s organisation, Anjuman-e-Khuddam-e-Ka’aba, in 1914 to support the Khilafat.

Later, as one of the initiators of the Khilafat Movement, “My grandfather was criticised for supporting the pan-Islamic political campaign, but he would explain to the others that he was thoroughly aware that the Caliphate of the last Sultan of Turkey was corrupt, but he believed in a Muslim stronghold, similar to that of the Vatican; it was necessary to keep the Muslim world united,” says Aziz. The Khilafat Movement had picked up pace in 1920, when the Khilafat Manifesto was published, which called upon the British to protect the Caliphate and for Indian Muslims to unite. The Congress gave it support and the Khilafat Committee approved a non-cooperation movement and arranged for a nationwide tour of the Ali Brothers and Gandhi.

The Maulana wrote an article, ‘Choice of the Turks’ in The Comrade in 1914, following which the British government shut down the newspaper and decided to put him on trial. They confiscated his property and denied him entry into Rampur state.

(L) Maulana Shaukat Ali and Maulana Mohammad Ali known as the Ali Brothers.

Considered troublemakers, the Maulana and his brother, Shaukat Ali, were arrested and imprisoned in 1915, and for the entire duration of World War I, the authorities kept shifting them from one inaccessible location to another, to prevent people from converging there. However, they were allowed to have visitors and the family could stay with them as well — it was similar to a house arrest. While still incarcerated, the Maulana was elected president of AIML in 1917, and in 1918 he raised his voice against the British government’s Simon Commission that was to determine the future of India without including a single Indian member in the commission.

Nationwide protests against the imprisonment of the Ali Brothers followed and, finally, on December 25, 1919, after four years they were released. Five days later, Maulana left for Amritsar to join the combined protest march of the Congress, the Khilafat and the Muslim League. He spoke against the passage of the Rowlatt Act 1919 (a legislative act that extended indefinitely, the emergency measures of preventive indefinite detention and incarceration, without trial and judicial review). “The politics of the time was different, with the Hindus and the Muslims working closely together to get rid of the British Raj,” says Aziz. “Imagine Gandhiji supporting the Khilafat Movement. The division between the Muslims and the Hindus did not happen till much, much later.

“I had heard about a fascinating friend of the Maulana’s called Waliyat Ali Bamboo. He was a mysterious character who would write satirical poetry for The Comrade. The story goes that he smuggled out classified documents of the British from a printing press they used. Since the staff was searched entering and leaving the premises, he would place the inside of his dhoti on the press and print all their top secret information and walk out with ease and share them with his circle, which included the Maulana and Gandhi.”

At Kakri Baghicha in Lyari, the Maulana gave a speech, to try to convince those Muslims and Hindus serving in the British Army and police to resign, instead of killing each other. In a speech at the Khilafat Conference in Karachi on July 9, 1921, he declared that it was haram for Muslims to join the British army and kill fellow Muslims. Consequently, the British government arrested him in September at the Waltair Station, (Andhra Pradesh) and he was brought to Karachi to face charges of ‘Sedition against the armed forces.’

For the Maulana’s trial in 1921, the British government turned the Khaliqdina Hall in Karachi into a court. Shaukat Ali, Maulana Ahmed Hussain Madni, Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, Maulvi Nisar Ahmed Kanpuri, Pir Ghulam Muhammad Mujaddid Sirhindi from Matiarvi, Sindh, and Sri Shankar Acharia were tried alongside. To commemorate his 100th anniversary, his eldest daughter Zohra, in an interview to Radio Pakistan, said that when his trial was being held, the roads to the hall would fill with crowds, that included large numbers of Sindhi women. And Bi Amma and his wife, Amjadi, would make fiery speeches before the crowds. After being sentenced to two years rigorous imprisonment, in October, the Maulana was sent to the Karachi Central Jail, and after some time to the Bijapur Jail, Karnataka.

The Jauhar brother’s firebrand mother, Abadi Begum, called Bi-Amma.

“Till today there is a Mohammad Ali Barrack No. 10 at the Karachi Central Jail. I visited this barrack once and it comprised three very tiny rooms. I don’t know how he fit because my grandfather was not a tiny man. He planted a peepul tree, which, I believe, still grows,” shares Aziz. “Political prisoners were treated no differently to regular prisoners,” she continues. “They were given terrible food, no medical aid, had to grind corn and wear shorts. My Nana would protest that it was not possible for him to offer his prayers under such circumstances. But the jailers stuck to their rules and the Maulana stuck it out.”

Aziz recounts that, “During his two-year imprisonment, Amna, his most beloved daughter, lay dying from tuberculosis and it was rumoured that he might be compelled to apologise to the British government so that he could visit her. But his mother, Bi Amma, assured him that she still had enough strength left in her hands to strangle him if he ever dared to act repentant before the British.” Bi Amma, meanwhile, toured several places, giving fiery speeches and in a recently discovered CID report on her activities and speeches, she is said to have incensed the British, referring to them as “monkeys,” when addressing public gatherings.

After his release from Bijapur Jail in 1923, the Maulana was elected President of the Indian National Congress. During the Hindu-Muslim riots of 1923, Gandhi came from Ahmedabad to stay with him in Delhi and began his 21-day fast to stop the bloodshed. Till then, the Congress and Muslim League were working together to free India from colonial rule. The real split between Muslims and Hindus happened after the Nehru Report in 1928.

Shuaib Qureshi, the Maulana’s son-in-law, who had been the Secretary of Congress for many years, registered his protest against the Nehru Report and resigned. “That is when the Maulana and other Muslim Leaguers realised that the Muslims would not have any say in anything after Independence,” says Aziz.

The Maulana’s intensive struggles took a toll and, despite his deteriorating health, he travelled to the UK in 1930 to attend the first Round Table Conference at the invitation of the Viceroy. In his memorable speech to the British government on November 19, 1930, he said, “I would prefer to die in a foreign country so long as it is a free country, and if you do not give us freedom in India, you will have to give me a grave here.” The following year on January 4, 1931, the Maulana died of a stroke in the UK at the age of 52 and his burial near the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem was arranged by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Aminul Husseini. The inscription on his grave says: “Here lies al-Sayyid Muhammad Ali al-Hindi.”

The Maulana’s wife, Amjadi Bano Begum, who was highly involved in the freedom and Khilafat movement, became the only woman to have signed the Pakistan Resolution. “She remained an active member of the Muslim League Working Committee and Jinnah had tremendous regard for her,” says Aziz. “When I was about nine years old, she took my younger sister and I to a public meeting in Allahabad. The Quaid was sitting on the dais with other important members while their children, including us, were sitting on the steps. From the crowd people would consistently hand us slips of papers to get the Quaid’s autograph. At that time not understanding the significance, we would dutifully run to get them, interrupting him so many times that he was a bit annoyed.”

Out of the Maulana’s four daughters, two had died young, of tuberculosis. The eldest, Zohra, married his nephew, Zahid Ali, who ran a paper, Khilafat. “My mother, Gulnar, was the youngest and my father, Shuaib Qureshi, approached Maulana Jauhar for her hand. They both had tremendous respect for each other because my father, who also studied at Oxford and was also an able journalist, was part of the Khilafat Movement and a member of Congress. My mother was only 17 when she was married to my father, who was 20 years older, but I have never seen a happier, well-adjusted, loving couple. In all, we were seven sisters and two brothers, one died when only two years old,” says Aziz.

Karachi 1921: L—R Maulana Shaukat Ali, Sri Shankar Acharia, Maulana Mohammad Ali; front Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, on trial for ‘sedition against the armed forces’ in Khaliqdina Hall.

“When I was studying for my matric, the main topic of our conversations was the partition of India. In our hearts we knew it was imminent, because we would hear about communal riots with increasing frequency and wondered how we would move. The Nawab of Bhopal had assured the Hindus in his state that they had nothing to fear. Our geography teacher had said we would have to migrate to a place called Kurrachee. I didn’t know where it was.”

“A vivid memory from 1946 is of our return trip to Delhi with our father from Kashmir, after meeting the Maharaja of Kashmir. The plane flew very low over Lahore and that’s when I literally saw people below scattering in a panic — they were running for their lives from an ongoing massacre. I saw chaos, swords, blood and people being felled.

“Another memory of 1946 is of an order passed by the British government that all citizens were required to surrender their guns, revolvers, rifles, swords, daggers and any knife beyond 10 inches at the police stations. Most Muslims, like fools, deposited their arms, not knowing what was to happen — while the Hindus kept theirs. That very day the killings started in the morning, when the men were not home and the women were trapped inside with their children, not knowing how and where to escape. The rioters, mostly Sikhs, had barged in, killed the elderly women, raped the younger ones, and taken some of them away — there was nothing anyone could do.”

Aziz continues to recount, “What was earth-shattering for me was this one train that was coming, most probably from Delhi, for a stopover at the Bhopal Station. The travellers on this train were all Muslims, senior as well as junior government officers and their families who had opted for Pakistan. The Nawab of Bhopal had arranged to provide them with lunch and we had decided to accompany our father to greet them.

“When we arrived at the platform of the railway station, my father suddenly turned towards us with an ashen face and said, ‘Go back. Just get out of here. Don’t look down.’ The minute he said that, I simply had to see what he didn’t want us to see. It was the bloodiest sight. As the train passed by, there was blood streaming out from every part of the train. The long tresses of women, I think, were hanging from the doors and windows; there were broken bangles on the floor — the people inside all lay dead.

“Apparently, this had happened when the train made a stop at Gwalior station, which is next to Bhopal. Many of the girls on the train were raped, some were taken away and some killed in front of their fathers. One of our relatives by marriage was on that train and his body was never found.”

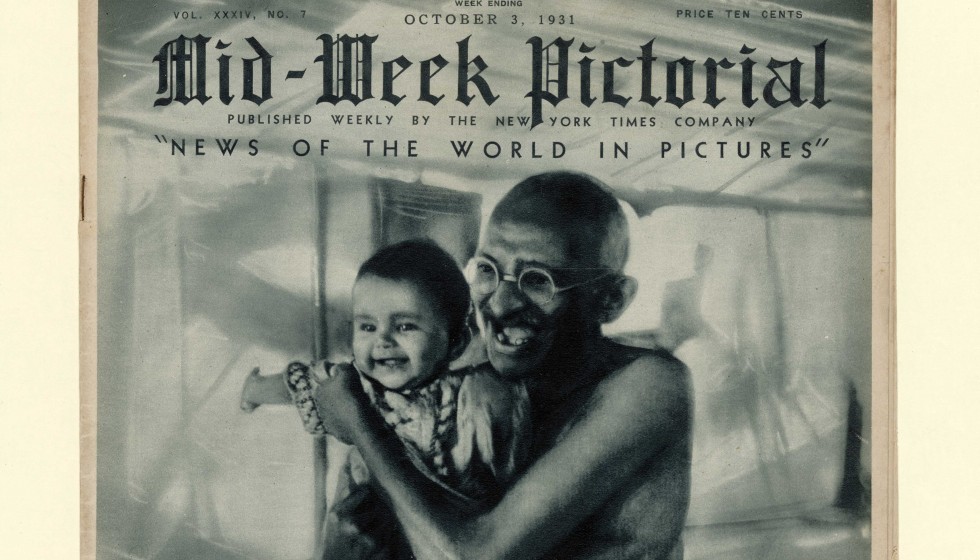

1931: On the cover of The New York Times, six-month-old Aziz Fatima with Gandhi on the SS Rajputana when Gandhi was travelling to the UK to attend the 2nd Round Table Conference.

Another memory Aziz has is of an abandoned airport in Bhopal that was used by the British during WWII to house Italian POWs. It was turned into a huge medical encampment called the Bairagarh camp. “We had heard that severely wounded people were arriving, so my sisters and I decided to provide them first aid. I saw a man with an axe stuck in his head with worms crawling out of his wounds. There were others with injuries that were equally horrible. The injured were all Muslims, who had escaped from the various Hindu-majority states around Bhopal. From them, we heard of how they were lured into forts under the guise of protection and were killed when they entered .”

Recalling the riots of Bihar, Bombay and Calcutta, Aziz says, “We heard news of Hindu-Muslim riots in Bombay, but it was nothing new; the communal riots of Bihar in 1946 were equally horrific. My husband’s uncle, Abdul Rehman Siddiqui — a prominent figure and a member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly 1937-1946, the elected Mayor of Calcutta, (1940) and for a few months the Governor of East Pakistan in 1952 — who was living in Calcutta, narrated some unspeakable incidents in Bihar. He spoke of the unknown number of women who had jumped into wells to avoid being raped by the Hindus. Some of them were taken out of the wells and at a mela called Gurmukh, they were made to undress and paraded naked before the crowds, and the men would touch them and even cut their breasts. Can you image anything more horrendous?

“A similar type of violence spread to Calcutta. A Muslim officer working with the British ambulance service in Calcutta narrated a particularly gory story: during the communal riots, he found a pregnant woman lying on the ground half-dead. He thought the very least he could do was fetch an ambulance to save the unborn child. When he returned with the van, he found that her stomach had been ripped open and the baby had been pinned with a sword, and a note that said, ‘This is your Pakistan.’ Enraged, the officer felt justified at what he did next. He went around shooting Sikhs, killing several to appease his need for revenge for what was done to the woman and baby.

“These incidents upset us all very much because we thought that we would celebrate the Partition by lighting diyas with ghee and decorating our homes and other places. At that age, I didn’t think that the actual partition would be so bloody — that there would be so much slaughter.”

Aziz’s departure from Bhopal, where her father, Shuaib Qureshi, worked as a senior minister, is a blur, “All I can recall is that I had looked around my room for the last time, wondering if I will ever see it again. The communal rioting and killings around us had reached a point where my parents decided to leave with the family and join an uncle in Bombay, before departing for Karachi. In Bombay, the Nizam of Hyderabad asked my father to work in Hyderabad but a socialist politician, Chandra Shekhar Azad, told my father, ‘Shuaib Sahib, I think you’d better go to Pakistan, because things are never going to be the same again.’ In fact it got worse.”

Aziz recalls how her family settled into their new life in Karachi: “We arrived by boat in 1948 at Karachi Harbour’s East Wharf, during the mid-summer’s rough monsoon season. My first impression of Karachi was of unbelievable dust, camels and camel carts everywhere. I had only seen horses and cars before. Maulvi Abdul Haq, heading the Urdu College, arranged for us to stay in some rooms at the Urdu College, promising that everything would be prepared for the family to settle in comfortably when we arrived. However, we found the place locked when we reached. Finally, when the key arrived, and we opened up the rooms, there was a thick coat of dust on everything. My mother, a real trooper, attacked it with a vengeance and had arranged for beds by the evening. Between all of us there were just three rooms — one where we slept, another to store our luggage, and a third larger room which served as a dining area and would double as a bedroom for my brother and a cousin.”

Jerusalem 1931: The funeral procession of Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar on its way from Port Said. His burial was arranged by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Aminul Husseini.

“The biggest problem was that there was no attached bathroom. Because there were several other people in the building, one person would have to stand guard while the others bathed and changed in the communal baths.

“My father became the Minister for Refugee Rehabilitation and he was responsible for all the refugee-related policies. His ministry’s first offices were inside tents where the staff would sit on crates. My parents established what is now Shah Faisal Colony and rehabilitated the arriving refugees in this new colony.

“I remember hutments and hundreds of people on the roads, starting from the DOW Medical College and leading right up to Karachi Jail. And yet there was no rioting; no one raised their voice in anger or complained about anything. The people living on the roadsides were very decent, including famous musicians and artists like sitarist Ustad Kabir Khan and sarangi player Ustad Bundoo Khan who performed on Radio Pakistan.”

Shuaib Qureshi’s close friendship with Abdul Rehman Siddiqui from Aligarh University days would turn into family ties through Aziz’s marriage. Earlier, both friends had vowed never to marry and only to serve their country. Siddiqi never married but my father married my mother, Gulnar, the Maulana’s daughter, and settled down. Siddiqui now wanted that one of Qureshi’s children be married to one of his sister’s sons — the one closest in age. That is how my match was made with my husband, Zainulabiddin Kamaluddin Kazi, who was 10 years older,” remembers Aziz.

“I have always been very vocal and people would often tell my husband to ask me to temper my opinions. I have not pursued a career because I preferred being a hands-on mother to my four children — my three daughters, Durriya, Faiza and Muna who have been in teaching for decades, and my son, Salahuddin, an exceptional doctor who lives in the US with his family.

“Being a witness to history, I found it ridiculous how often governments kept changing during Pakistan’s initial years, after Jinnah and Liaquat passed away — sometimes after every 15 days — until Ayub Khan came to power. A prime minister would leave for England and upon his return find out that he was no longer prime minister of the country. The most shocking incident after Partition was Liaquat Ali’s assassination. Said Akbar, who shot him twice during a public meeting was sitting right in front of the stage in the fifth row.

“After Partition there were cases full of letters arriving from India from wives who had been snatched from their husbands and wanted to know if their husbands were willing to bring them over from the addresses they had provided. My father’s dhobi Islamuddin’s wife had been kidnapped during Partition by a Sikh and had two sons by him. My father advised him to take her back, because what had happened was not her fault. He did, but neither he nor society fully accepted her two sons.”

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.