To Talk or Not To Talk

By Syed Talat Hussain | Cover Story | Published 12 years ago

It was supposed to be as simple as 1, 2, 3. In order to silence opponents of the use of force to deal with the militants holed up in North Waziristan, the hub of terrorism in the land, a peace effort would be mounted, backed by all the political stakeholders including Imran Khan, Chairman Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, who believes that the Taliban can be weaned away from violence by waving the white flag at them. And if this peace effort were to run into any snags and collapse because of the impossible demands of the militants (which necessarily includes stripping the country of its Anglo-Saxon legal and constitutional base and the imposition of Shariah of the most hide-bound Salafi brand), the alternative option of a military operation would become inevitable, forcing even its worst critics to swallow it.

The bigger disaster was yet to come. The meeting that mandated the federal government to talk to the Taliban (and scrupulously avoided the use of the term ‘terrorists’), could not work out the basic methodology of the proposed talks or suggest a cut-off point beyond which terrorism would be tackled through the barrel of the gun rather than through the wagging of the tongue.

But like the battle plan that does not survive the first bullet fired, the grand idea behind the All Parties Conference to deal with terrorism in the country became barely recognisable once Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, Imran Khan and General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani got together just before the bigger meeting of the political parties was to commence. Agendas clashed. Second-guessing ensued. Mian Nawaz Sharif wanted General Kayani to be the frontman to explain to Imran Khan, ever queasy about the use of force in Pashtun heartland, of the chances of success of such talks. The general, looking to the political leadership to make up their minds and forge consensus on a final policy guideline against the militants, did not want to be the focus of attention and controversy. Khan, who had shared his objections to this core meeting being held on the day of the All Parties Conference, had to make use of the limited time to get his most ardent wishes included in the final draft to be issued at the end of the bigger meeting. So Sharif hedged his bets on what his real thoughts were on dealing with the Taliban. The general plodded through by committing to clearing North Waziristan’s main areas of the Taliban in weeks, but qualified this anticipated success with the assessment that, even so, terrorism would not come down by more than 40 per cent. Imran Khan dwelled more on the drones issue than anything else and skipped the tricky issue of proposing an alternative to the presence of the army in the FATA area.

The meeting ended rather ingloriously as Nawaz Sharif never returned to the room after excusing himself to attend the call of nature and Imran Khan, who was itching to bolt the moment Sharif left but was requested to stay and wait for the prime minister to return, lost patience and scurried out minutes later.

The bigger disaster was yet to come. The meeting that mandated the federal government to talk to the Taliban (and scrupulously avoided the use of the term ‘terrorists’), could not work out the basic methodology of the proposed talks or suggest a cut-off point beyond which terrorism would be tackled through the barrel of the gun rather than through the wagging of the tongue. Since then, the country has gone into convulsions primarily on account of the big-ticker terrorism acts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa that have targeted civilians, minorities, government officials and high-ranking security officials, causing hundreds of deaths and destruction of the lives of even more through life-long injuries and disabilities.

Compounding the tragedy is the fact that talks with the Taliban have acquired a strange currency on the back of the the popular theory that the ‘enemies of the talks’ are subverting the peace process. Besides justifying, in a back-handed way, that these tragic terrorism incidents are some sort of a cost of making peace, this deranged debate about whether talks are failing or succeeding has no empirical basis. The government is completely silent on the subject of who is talking to the Taliban and when this process would be allowed to come to a logical end. When contacted for information, a close aide of Prime Minister Sharif had only this to say: “There are retired bureaucrats, generals, local power-brokers and religious parities, including the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam of Maulana Fazlur Rehman and Maulana Sami-ul-Haq, who are in the field talking to assorted groups of the Taliban. Intelligence agencies are also involved in some of these conversations. The Punjab group’s representatives in our custody are also being used to look at the possibility of convincing their organisations to lay down their arms and agree to be integrated back into the constitutional order.”

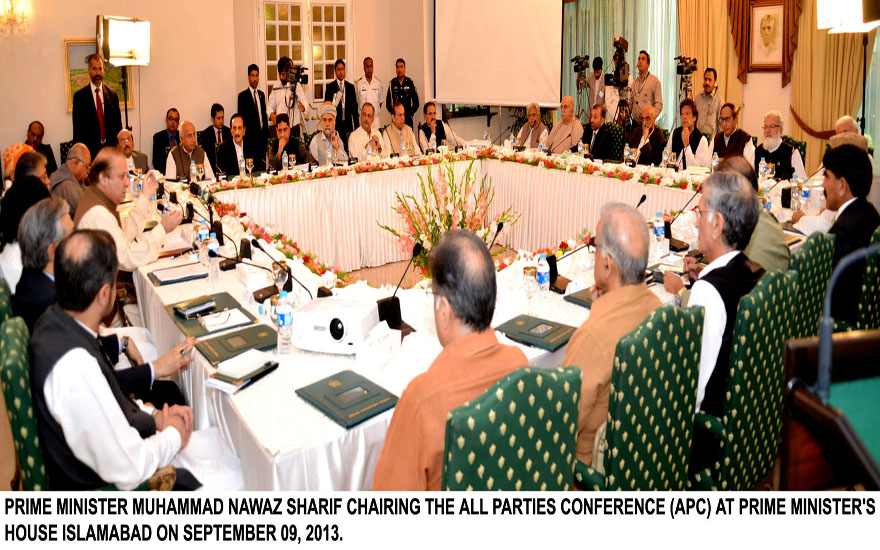

Who’s calling the shots? : General Pervez Kayani, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Chairman Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf Imran Khan.

That, however, is one part of the story. In the circles of security forces, there are any number of sources who would speak to you on condition of anonymity, about the central role of the ISI, along with the IB, on brokering this dialogue.

“Who to talk to, is a crucial question. This relates to the information that we have about these groups and who their backers and funders are. For instance, groups like those who sit closely with Hakimullah Mahsud and are funded directly from Afghanistan will not talk. Nor is there any need for us to talk to them. Others are keen and we are talking to them,” says an intelligence officer based in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. He was quick to add that “all dialogue is being supervised by the interior ministry under guidance from the prime minister.”

But not everyone in the loosely aligned Tehrik-e-Taliban camp, which matters in this rather chaotic attempt at making peace through dialogue, is on the side of engagement with the government. The Mohmand chapter of TTP has spoken against the dialogue by issuing a formal letter. And the Swat chapter has made its intentions known by killing Major General Sanaullah Niazi, GOC, Malakand Division and his aides through a coordinated attack. Only the Punjabi Taliban faction is making a public pitch for peace through talks.

This makes the picture even more blurry than before. The divisive debate about the Taliban’s sincerity or lack thereof is a godsend for any number of factions to soak the land in innocent blood and use these attacks as a way to prove to their funders and backers (allegedly in India, Afghanistan and the Middle East) that they have the capability to strike deep into the heart of Pakistan. An Islamabad-based intelligence officer believes this assessment to be true: “I would say that, in general, you are right that many of these groups use these incidents as marketing tools. They make videos of the trail of death not just for the media but also to showcase their influence and spread of operations. It is on the basis of this performance that they are allocated funds from abroad.”

These opportunities to sell the blood of Pakistanis for funding could have been denied to them if the All Parties Conference and all its participants had decided on a course of action to manage the issue of terrorism in those weeks and months when the various teams were engaging with various Taliban factions. Nothing of the sort was done. Now the state machinery is paralysed because most institutions are not sure which way the talks are going to go; political parties are pushing their for-and-against case on a dialogue and their positions are getting ever divergent, difficult and even astoundingly absurd. Imran Khan’s suggestion that the Pakistani militants should be allowed to open an office to conduct peace talks à la the Doha office for the Afghan Taliban, shows the depth of his desperation to prove that PTI’s stand is correct and workable. The chief minister of Khyber Pakhtunkwa, Pervez Khattak tried hiding his own gross incompetence with the inane argument that the Pakistani media was to be blamed for the spate of terror attacks because it gave them publicity.

All this indicates that the whole strategic plan of crafting a national consensus on a uniformed policy to deal with terrorism on a long-term basis has been put through the shredder. The country is far more divided than before — and bitterly so — and the ordinary citizen’s sense of vulnerability has increased manifold.

It is against this background that the army chief, General Kayani has made some extraordinary moves to get the momentum going by insisting on acquiring clear policy guidelines from the political leadership. In a string of meetings with Interior Minister Chaudhary Nisar Ali Khan and Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif, he pressed for early conclusion of the process. According to PML-N sources, the general has repeatedly said this to the government representatives: “Time is short for the other option. The winters are not conducive for any military operation. By the end of October, things have to be clear as to the parameters of political consensus.”

It is against this background that the army chief, General Kayani has made some extraordinary moves to get the momentum going by insisting on acquiring clear policy guidelines from the political leadership. In a string of meetings with Interior Minister Chaudhary Nisar Ali Khan and Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif, he pressed for early conclusion of the process. According to PML-N sources, the general has repeatedly said this to the government representatives: “Time is short for the other option. The winters are not conducive for any military operation. By the end of October, things have to be clear as to the parameters of political consensus.”

Not everyone in the loosely aligned Tehrik-e-Taliban camp, which matters in this rather chaotic attempt at making peace through dialogue, is on the side of engagement with the government. The Mohmand chapter of TTP has spoken against the dialogue by issuing a formal letter. And the Swat chapter has made its intentions known by killing Major General Sanaullah Niazi, GOC, Malakand Division and his aides through a coordinated attack.

Not everyone in the loosely aligned Tehrik-e-Taliban camp, which matters in this rather chaotic attempt at making peace through dialogue, is on the side of engagement with the government. The Mohmand chapter of TTP has spoken against the dialogue by issuing a formal letter. And the Swat chapter has made its intentions known by killing Major General Sanaullah Niazi, GOC, Malakand Division and his aides through a coordinated attack.

The army has also made contacts with Imran Khan and tried to convince him that clarity, rather than confusion, will serve the national purpose. “If it is peace, then let us all agree to work for peace. If it is war, then let us all agree to fight this war,” a GHQ emissary told Mr Khan, according to a military source.

But the politics of the counter-terrorism policy is not as simple as this black-and-white equation, which the military would want to see prevail. Imran Khan is unlikely to clearly state that he is not for the use of force even if all hell breaks lose across the length and breadth of KP. He would want Nawaz Sharif to bear the cross of this decision. Nawaz Sharif would want the army to play the lead role on the issue of conducting an operation. He would not even want to conclude the talks phase himself and state publicly that these have failed. The army, led by General Kayani, remembers the Kargil war very well. This time they would want the Nawaz Sharif government to give it in writing that the federal government wants them to clear North Waziristan. Not only that, the army would also want the political leaders to be willing to deal with the blow-back of the final assault. A classic case of everyone passing the buck — indicative of a paralysis of decision-making of the worst kind.

The writer is former executive editor of The News and a senior journalist with Geo TV hosting a prime time current affairs program.