Bill of Health

By Hilda Saeed | Health | Published 12 years ago

A middle-class woman anxiously awaits pay day; she’s an insulin-dependent diabetic, and has only enough insulin to last another week. What will she do after that? An exaggeration? Not quite — the scenario above is already unfolding in the country.

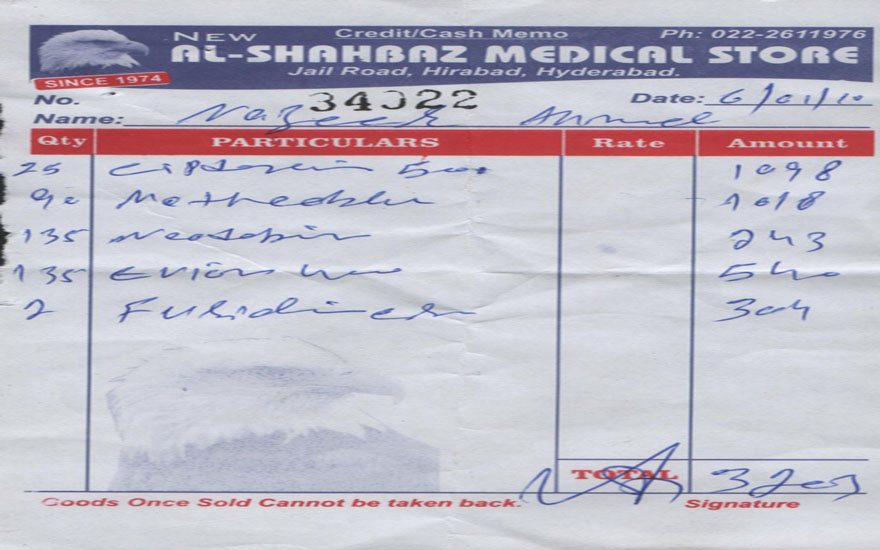

Another woman in a katchi abadi worries about her little son: he has typhoid, but she can’t afford to buy the needed medicines. A teenage son fears for his father, a cardiac patient: his medicines cost nearly Rs 4000 each month. The family has been able to get them by scrimping on their food budget, the only thing they can scrimp on.

These are scenes repeated in millions of homes across the country; the story has remained the same for years. High medicine prices are affecting both the rich and the poor alike; there seems to be no solution.

The complexity of the situation isn’t due to the prices of pharmaceuticals alone; the roles played by the ministries of water, power and sanitation; finance; and population — and the key role played by the ministry of health (MoH), all need to be considered.

The last-mentioned is primarily responsible for the health of the population. Effective health care immediately cuts down the need for medicines, but preventive health care varies considerably. Access to pure drinking water, immunisation against communicable diseases, general hygiene, all improve chances of healthy living, while an absence of these basics pushes up the incidence of disease, with a matching demand for a variety of medicines.

The public has no alternative but to seek remedial measures in doctors and medicines. There’s a mind-boggling array of medications to choose from — as many as 27,000 pharmaceutical products are registered with the health ministry. The World Health Organisation (WHO), on the other hand, recommends an Essential Medicines List (EML), which comprises a mere 270 products, considered adequate to treat the most prevalent diseases.

So does the country really need all 27,000 medicines? Can we afford the huge expense of so many branded products? How many are duplications, ‘me too’ products, as they say in pharmaceutical parlance? And why do medicines cost so much?

Khalid Mehmood, of Getz Pharma, expresses concern about public health. “Look, we recognise that prices are high, in Pakistani terms, but that is because of the country’s economic situation and the large number of people living near or below the poverty line. Obviously, medicines cost money to manufacture and, in actual fact, our products are cheaper than in many countries. How much does the government sector spend on health care? A mere one per cent of the GNP, or even less. In the past 40 years, not one public sector hospital has come up anywhere in the country, although during this period, the population has grown exponentially.”

Consultant gynaecologist Dr Azra Ahsan too is concerned. “In treating any ailment, ethical doctors will go by whichever product is most efficacious. Unfortunately medical representatives give their opinions about a product, and many doctors follow this, rather than decide on the most effectual product — ignoring prices. Chemists also stock those products which have high profit margins.

“In my view, pharmaceutical companies have a high profit margin — they pay their employees well. Do their profits have to be so high?” She contends. “We’re aware of the unethical practices that go on. To work ethically in this atmosphere is difficult; education is about getting a degree, but unless we maintain a high moral ground, we cannot really do justice to our calling.”

As regards the high prices, Dr Ahsan’s opinion is that competition is necessary, but there needs to be a maximum ceiling beyond which prices should not be raised. Further, she’s anxious that post-devolution, no national Essential Medicines List (EML) has been announced, nor does the medical profession know who will be steering this.

The availability of the national EML is important both for public sector health facilities and the wider public. Its adaptation at provincial level will facilitate distribution of inexpensive, effective products.

Dr Tasnim Ahsan, Medical Director of the Jinnah Post graduate Medical Centre, an important public sector health facility, says, “We do make an effort to provide suitable medicines, and succeed in meeting about 80 to 85 per cent of the demand. Of course, I can only speak for my own hospital.”

Further, she adds, “Public hospitals are required to invite tenders for their medical supplies; from these, the best possible quotations are considered, depending on efficacy, cost, and whether purchases are in accordance with the guidelines of the Drug Regulation Authority; this body takes random samples for testing of quality. A mix of medicines from the WHO EML and branded products is usually selected. Personally, I’m satisfied with the supply position.”

In her view, “the hospitals simply cannot supply every needed product: monoclonal antibodies, for instance, are expensive, as are orthopaedic prostheses, or stents for cardio-vascular patients, but even in those cases, we try to meet patient requirements via zakat or Bait ul Maal funds. No patient is turned away for lack of funds.”

Then what’s the real story behind high pharmaceutical prices? The News (March 20, 2012) reported last year that price escalation was likely to create acute shortage of medicines in the country: the government attempted to control drug prices, and reportedly both domestic and multinational pharmaceuticals countered them by gradually suspending production — even of life-saving medicines.

There are also reports that obtaining a price increase for an existing product is easy — corruption is rampant in the corridors of power at the health ministry. Khwaja Shahzeb Akram of the Pakistan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association had at that time remarked that the last increase had been allowed in 2001; since then, the rupee had been heavily devalued, and the cost of living had shot up [and thereby affected prices].

The lack of facilities for local manufacture of basic raw materials necessitates the use of imported raw materials, and this is reflected in higher prices. Multinational Corporations (MNC) import raw materials only from their parent companies, on the grounds of stringent quality control. MNCs further state that their investment in Research and Development is extremely high — every new drug range costs around $ 350 -500 million to produce. It is only when a drug’s patent period expires that it becomes eligible for sale as a generic product, with lower pricing.

“A most disturbing aspect of the crisis of patents and drugs (medicines),” says Cecilia Oh of the Third World Network, “is that obstacles are put in the way of developing countries seeking to make use of Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) provisions on compulsory licensing or parallel imports, in order to buy or produce drugs at more affordable prices.”

In effect, a patient’s interests have moved to the back burner, and there appear to be few opportunities for lower prices.

A comparison of prices in India and Pakistan would be relevant: several Indian pharmaceutical products cost less than their Pakistani equivalents. Expectedly, smuggled Indian products are immensely popular. Aspirin, Amoxicillin, Amodin and Ampicillin are all doing brisk business in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and along the Pak-Afghan border. Under Pakistani law, imported medicines can be registered for legal sale, but in the case of smuggled Indian products, the country is losing revenue.

India’s prices remain consistently lower because they have introduced generic manufacture of pharmaceutical products (i.e. manufacture of the product by its chemical, not brand name) several years ago, making the production process a lot cheaper. India also manufactures its own raw material for production of medicinal products; thirdly, India requires, by law, the primary use of its own raw materials.

The end product is therefore sold at a fraction of the price of the branded equivalent. In fact, MNCs are thus able to manufacture more cheaply, and hence lower their own prices.

In Bangladesh, medicines on the WHO EML are readily available in the country: the government has identified the best available product to treat each disease, publicised and popularised these products, resulting in improved health for the public.

Here, on the other hand, the prices of pharmaceuticals escalate steadily. Visits by representatives of the pharmaceutical industry to personnel of the health ministry are frequent, either for registration of ‘new’ products, or for price increases of existing products, on the grounds of inflation and increased costs of electricity, fuel, labour, and raw materials.

In Pakistan, the prices of pharmaceuticals escalate steadily. Visits by representatives of the pharmaceutical industry to personnel of the health ministry are frequent… There are also reports that obtaining a price increase for an existing product is easy — corruption is rampant in the corridors of power at the health ministry.

The Islamabad-based Network for Consumer Protection carried out a nationwide survey in 2008, on Prices, Availability, and Affordability of Medicines. The group probed the difference in price of commonly-used generic and branded products; the affordability of Pakistani products, especially for people of low-income communities, and compared Pakistani product prices with comparative sales in neighbouring countries. Their findings:

Government sector procurement of medicines is efficient in getting low-priced medicines, but inadequate in supplying the needed quantities to government health facilities.

Prices of medicines in private pharmacies are generally lower than in other developing countries, but higher than in India.

Certain medicines are unaffordable to the poor; comprehensive interventions are needed to reduce inequity in access to basic medical treatments for a large part of the population.

The WHO EML was not well-stocked in every pharmacy surveyed, even for in-demand products like sulfadoxine+pyrimethamine (3.3%) and salbutamol inhaler (3.3%). In comparison, branded products were more widely available. Given that roughly 67 per cent of even the poorer population prefer to frequent private practitioners, it is crucially important that this vacuum of inexpensive medicines is addressed.

The Network advises the promotion of generic-prescribing by physicians, generic substitution by pharmacies; and assurance of high quality of all marketed generic products by relevant authorities, to build public trust in generic medicines. Such an exercise would be worthwhile; the difference between Lowest Generic Price and Medical Price Ratio means that the branded product can be twice as expensive as its generic equivalent. There’s need to bring these savings to the public by instituting corrective measures.

The prices of medicines and health care have eaten into household budgets, depriving poorer families of little luxuries like fruit or eggs — meat is already priced out of their budget range.

Pakistan has to make medicines available to the populace at reasonable rates, either by stepping up the use of the WHO EML, or introducing generic manufacture, or putting a freeze on prevalent prices, or officially importing from India, China, and Korea.

Or, best of all, use the experience of Bangladesh and India to learn, and profit by that learning. If other developing countries have adapted to the prevalent economic situation, why can’t we?