Pumping Poison

By Noorilhuda | Health | Published 9 years ago

The last 24 hours of Ali Farooq’s life were like those of any other modern young man in urban Pakistan: office, gym and dinner with friends. On October 3, 2016, a sunny Monday in autumn, the 26-year-old father of two girls, a toddler and a newborn, went to his office at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SECP), Egerton Road, Lahore. After work, he headed to a newly-joined gym for a workout and spent the night at his home in Zaman Park, where his father, Mohd. Siddiq-ul-Farooq, Chairman Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB), had arranged a dinner in honor of Governor Punjab, Malik Mohd. Rafique Rajwana. Ali ate little, but sat with his father for an hour after the get-together ended. He went to bed at 12:30 am. That was the last time Siddiq-ul-Farooq saw his son alive.

The last 24 hours of Ali Farooq’s life were like those of any other modern young man in urban Pakistan: office, gym and dinner with friends. On October 3, 2016, a sunny Monday in autumn, the 26-year-old father of two girls, a toddler and a newborn, went to his office at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SECP), Egerton Road, Lahore. After work, he headed to a newly-joined gym for a workout and spent the night at his home in Zaman Park, where his father, Mohd. Siddiq-ul-Farooq, Chairman Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB), had arranged a dinner in honor of Governor Punjab, Malik Mohd. Rafique Rajwana. Ali ate little, but sat with his father for an hour after the get-together ended. He went to bed at 12:30 am. That was the last time Siddiq-ul-Farooq saw his son alive.

The next morning, Ali did not go to office and was assumed to be resting. He was long dead by the time his father broke open the door with the help of servants that Tuesday night. The doctors at hospital declared the cause of death to be sudden cardiac arrest. No autopsy was performed — as per family wishes — and Ali was buried at the H-11 graveyard, in Islamabad, on Wednesday, October 5, leaving behind a shell-shocked family.

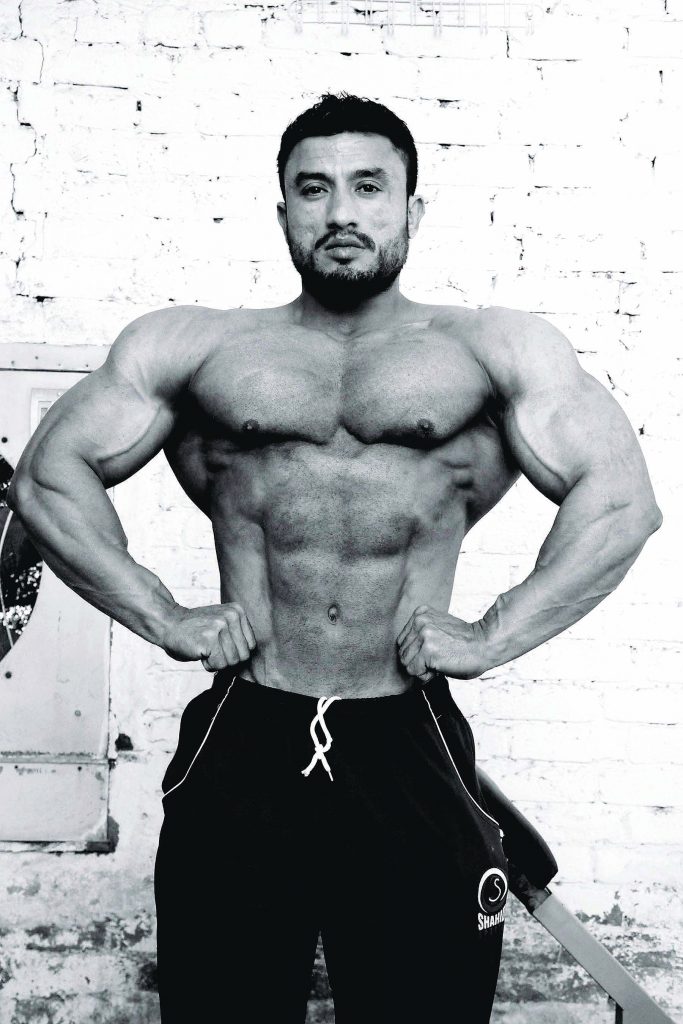

“He was athletic and very good in college sports,” says his father of his sporty, muscular son, one of his five children. In recent years, Ali had started taking an interest in sculpting his body, and began to take nutritional supplements to enhance this goal. Siddiq-ul-Farooq insists his son was not on steroids, but acknowledges he disapproved of the drugs Ali was using. “The supplements dry out the body, eradicating its water content. I used to tell him not to take these unnatural substances, but he didn’t listen. He started taking them after marriage three years ago. For a year in between, he didn’t use anything. Then he started taking them again, and once, he even asked us to get some supplements from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Bara Bazaar, because they were more expensive here.” Since his son’s death, Siddiq-ul-Farooq says he has heard of many other body-building-related deaths. “I just heard of a 25th case,” he states.

Men’s fitness has seen a change in recent years. “When Bruce Lee was the rage in the ’70s, judo-karate clubs were a common thing,” says a senior official working for the Drug Regulatory Authority Pakistan (DRAP). “Now it’s Indian movies. There is increasingly common usage of the term ‘six-pack’ in Pakistan. I live in Bahria Town (Islamabad) and see men walking on the footpath with their shirts off. It’s like one-wheeling — they want to show off, in this case, their sculpted abs.”

Unsurprisingly, given the demand, there has been a rapid growth of gyms which offer all kinds of weight loss, weight gain and muscle definition programmes. “You get a good body by controlling your diet and exercising. You’ve got to eat more proteins, less carbs,” says Bilal Malik, who teaches Asian philosophy and martial arts in Islamabad. “You will start to see a difference in three to six months.” But, he adds, “It takes two years to develop a lot of muscles. With steroids you can get big muscles in a short time.”

Body building and fitness is a lucrative — and, given the potential dangers, a murky — business. It consists of five basic components: drugs and nutrition/food supplements; gyms/trainers; the role of the federal and provincial authorities; and consumers.

Different steroids, growth hormones and dietary supplements are used at various stages and cycles of shaping the body: for strength, for ‘bulking’ i.e. gaining weight, for ‘cutting’ (i.e. fat burning and body shaping), for preserving muscle mass, and for developing lean muscle through further cutting while lifting weights.

Steroids are unarguably legal life-saving synthetic hormone prescription medicines, used to treat various ailments ranging from asthma and anaemia to heart attacks. But anabolic/androgenic steroids are also used for performance enhancement, muscle recovery, strength and gaining quick muscle mass — all of which is illegal. And excessive and prolonged use of these steroids can have debilitating — and sometimes, deadly, side effects. Given the extent of their usage, however, the dangers don’t seem to have deterred people from using them. ‘Clenbuterol,’ ‘Anavar,’ ‘Winstrol,’ to name just a few of these substances, are popular among professional and amateur bodybuilders in Pakistan.

Nutritional supplements are easily available over the counter and require no prescription. Large weekly doses of proteins, creatinine, multi-vitamins/anti-oxidants and essential fatty acids (Omega 3-6-9) build muscles, but steroidal intake is only too common in conjunction with them. And given the fact that even mega doses of over-thecounter vitamins without medical supervision can be dangerous — for e.g. a vitamin D overdose could lead to kidney failure — the intake of steroids alongside these can prove fatal.

Unfortunately, gyms, pharmacies and the internet all contribute to the unregulated and uninformed usage of potentially dangerous substances.

“Drugs are not only a sports issue; they are also a societal issue,” says Dr. Waqar Ahmed, the head of the anti-doping department of the Pakistan Sports Board, Islamabad. “Illegal drugs are within easy grasp of everyone. People can simply go to a counter and get them. They don’t understand they are buying death. Steroids make the body big, but they also cause kidney, liver and brain damage. And supplements are not even labelled properly. They say they are one thing, when they are something completely different. This, especially in cities like Gujranwala and Faisalabad.”

Dr. Ahmed believes that the trend of boys wanting to pump iron (and drugs) owes to their desire to look attractive and impress girls. “They want to show they have good biceps, good triceps, great bodies, and are willing to do anything towards this end. Many users are virtually illiterate, or plain ignorant. So when a gym master says ‘buy this or that,’ they do. They don’t realise that for the owner of the establishment, the real money comes through the side business of selling supplements and steroids — sometimes even veterinary injections — to clients.”

Twenty-eight-year-old Mohammad Abbas is the owner of Jacked Nutrition (JN), a high-end enterprise offering exercise, nutrition plans, imported food supplements, apparel and accessories. He has four stores: two in Islamabad, one in Rawalpindi and one in Lahore, in addition to the CrossFit Gym. He claims 400-500 people (mostly men) visit the JN website daily, seeking e-commerce services (online purchases and Skype tutorials) and on average, 6-10 people daily visit any one of his stores. Gym registration costs Rs. 15,000, the monthly fee, 8,000 rupees, and an online tutorial Rs. 10,000. Three years ago, Abbas left his auditing job to launch the fitness business from his home in F-11 Islamabad as a sole proprietorship. Since then, he has seen a mushroom growth in Pakistan’s fitness industry. “The reason is social media. People log onto Facebook, see guys with great physiques, and start researching,” says Abbas, whose own toned body is proudly displayed on the JN website. He adds the supplements he carries in his stores — costing between five to 10,000 rupees a bottle — “are legal.” But he adds, “steroids are illegal: usage of these is a personal choice. And sportspeople often use them. But I admit it’s our job (those in the fitness industry) to educate men — tell them they don’t need steroids to look like the guy in the magazine.”

Gyms like JN come under the purview of the district government, but there is no cyber law in Pakistan that deals with online drug-related fraud, online pharmacies, online fitness services or the quality of online trainers. Sites such as http://imported-medicine.blogspot.com/ have open forum discussions between users and sellers — where no one asks for a prescription, and from which, according to a DRAP official, some drugs being promoted have been found to be spurious.

Professional body-building gyms are generally affiliated with the Pakistan Body Building Federation (PBBF), which is a member of the International Body Building Federation. It is one of the 38 disciplines associated with the Pakistan Sports Board. After the death of four bodybuilders in quick succession in April this year, Sheikh Farooq Iqbal, President of the PBBF, announced that gyms would need to give an ‘undertaking’ that they would not use or sell steroids. According to him, till October 2016, almost 100 gyms from all over Pakistan complied with the order. However, it is an open secret in body building circles that steroids are an important component in athletes’ preparation for assorted competitions. So, undertakings notwithstanding, how many athletes actually desisted from using them, remains anyone’s guess.

“Without steroids, there is no body-building, either on the national or the junior level,” says Adeel Sultan Malik, owner of the Iron Man Gym, Peshawar Road, Rawalpindi. Now 32, Malik has been a professional body builder for the last 17 years and has won the titles of ‘Mr. Punjab’ (2005), ‘Mr. Capital Zone’ (2007), ‘Mr. Super Pindi’ (2007), ‘Mr. Rawalpindi’ (2008), ‘Mr. Olympia Punjab’ (2010) and ‘Mr. Rawalpindi Division’ (2010). “You need steroids to shape the body — i.e. to bring the body into a lean, non-fat form — as well as to enhance body size and for ‘cutting,’ which relates to the hardness of muscles,” he adds. He continues, “Steroids are a shortcut towards this end. They are even used to make veins more visible. A contestant may have to drop or gain 12 kilos a night before the final of the sport he is participating in. This he does through food and supplements. Once a contest is over, steroids have to be taken out of the body through a process called ‘cleaning.’ Nobody knows how to do that. A user has to take antibiotics alongside anti-cancer medication (to counter the side effects of steroids). And most gyms sell these products without having the needed knowledge to prescribe, administer or sell them, to people who are even less informed.”

No autopsies were conducted in the case of Hamid Ali Gujju, Mohammed Rizwan, Humayun Khurram and Matloob Haider, the four bodybuilders, whose deaths prompted the “no selling of steroids” undertaking gyms were forced to give. All were reported to have died of heart attacks.

“Gujju was a good friend but his death was entirely his own fault,” says Malik. “He should not have injected the steroid he was using intravenously. The injectable is oily and there’s a 90 per cent chance that it will get stuck in one of the heart arteries if injected intravenously.”

Malik has two doctors, a surgeon and a nutritionist, on his payroll. He only accepts students interested in hardcore training and currently personally trains 20 of the 70-80 gym members at his gym. “I see what their goal is, and accordingly, tell them up front, what the cost of the steroids, supplements and training which I provide, will be. They also bear the cost of the diet they decide upon. On average, the minimum cost of all this is anywhere from two to three lakh rupees. But the cost of the fitness programme also depends on which competition the person is training for. For example, ‘Mr. Pindi’ is a small contest as compared to ‘Mr. Punjab.’ The nine-month training period for that can cost six to eight lakh rupees.

Malik won the ‘Mr. Punjab’ title in 2005. Two of his students, Toheed Anwar and Mohammad Shoaib, have won various titles as well. Twenty-three-year-old Toheed Anwar won ‘Mr. Rawalpindi’ in 2013 and ‘Mr. Abbotabad’ in 2014. Shoaib, 25, a superintendent at a popular cash and carry in Rawalpindi, won Mr. Faisalabad, in 2016. Both have earned certificates and trophies, but earn their living as online bodybuilding tutors via Facebook and Skype. However the real money is made through bets. As Malik says matter-of-factly, “I have earned lakhs from competitions. There are nine poses and an athlete usually knows which poses he is good in. Once an athlete wins his category class (i.e. body weight as per height category), the betting audience comes forward and tells the athlete that they will bet x amount on him in the final stage. The winning bet is then split 50-50 between them and me.”

Says Toheed, “The average cost of body maintenance is Rs. 50,000 a month.” “I eat 40 eggs a day. The government should either give us sponsorships or jobs. It’s not like we are illiterate.” Betting then is the bonus that brings in the extra bucks.

Malik now has his eyes set on ‘Muscle Mania Pakistan’ to be held early next year in Lahore, which is the qualifying round for the Asian Championships in Qatar in 2017. He has been training for this competition for two months, and has five more months to prepare. Weighing in at 112kg, and 6.1” tall, he has to increase his body weight to 145kg by January, and then shed it by 35kg (for muscle definition/ cutting). This requires following a gruelling discipline, including a diet that consists of eight meals and eight litres of water a day. The food comprises boiled egg whites, hot oatmeal, grilled chicken, grilled fish and fruit. The portions of each helping are huge. And these are accompanied by protein powder and tablets.”

Competitors also need to exercise. For Malik this translates into three two-hour long sessions in 24 hours. In addition to all of this is the daily intake of substances, usually smuggled in from Karachi and Kabul. Malik laments the status of the drug industry. “Spurious copies of drugs are being made in Pakistan, and they are useless — if not plain dangerous. I have been getting steroids from Thailand — there are two companies sending products from there, but after the deaths (he says he has heard of 10 in the past six months), there have been rumors that the Thailand batches are contaminated. So now I am thinking of getting them from India, which will be costly, but probably safer,” he says.

According to DRAP, consignments usually enter the country through misrepresentation, labelled as ‘textiles’, or ‘cotton,’ and are easily available without any checks. The local dietary supplement business is growing as well.

Says CEO, DRAP, Dr. Muhammad Aslam. “Around 300-350 manufacturers are licensed under our Health, Alternative Medicine and Over-The-Counter Division. In just the last one year, almost 100 companies have been given licenses to make such drugs.”

How one uses such drugs is, however, key to his/her personal welfare. Perhaps the best advice a user can get is from 86-year-old Mohammad Ilyas, the still-healthy, lean-muscled, active owner of Eagle Health Club, Gawalmandi, Rawalpindi. Formed in 1949, the club is one of the oldest bodybuilding gyms in Pakistan. Over the years, Ilyas has helped others set up their own establishments. He is a regular judge and speaker in bodybuilding competitions. The father of nine says, “Wake up early, eat well, exercise and keep a clean mind. You don’t need any thing else.”

The writer is a freelance journalist.