Lahore’s Smart Future

By Aasim Zafar Khan | Newsbeat National | Published 9 years ago

Lahore’s landscape has been changing at such a rapid pace that a little bit of work here and there usually goes by unnoticed. But not for the discerning eye. All across Lahore, at red lights and markets, outside schools, banks and heritage sites, work is underway, undersigned by the Punjab Safe Cities Authority (PSCA).

Now, the PSCA is a big deal in Lahore. But apart from Islamabad, nobody is entirely sure of what the PSCA is/does. Thanks to all the press coverage though, the entire country knows that the project is mighty expensive. Nearly Rs 14 billion in Islamabad, and 13.7 in Lahore. The two combined are more than the entire health budget of the country.

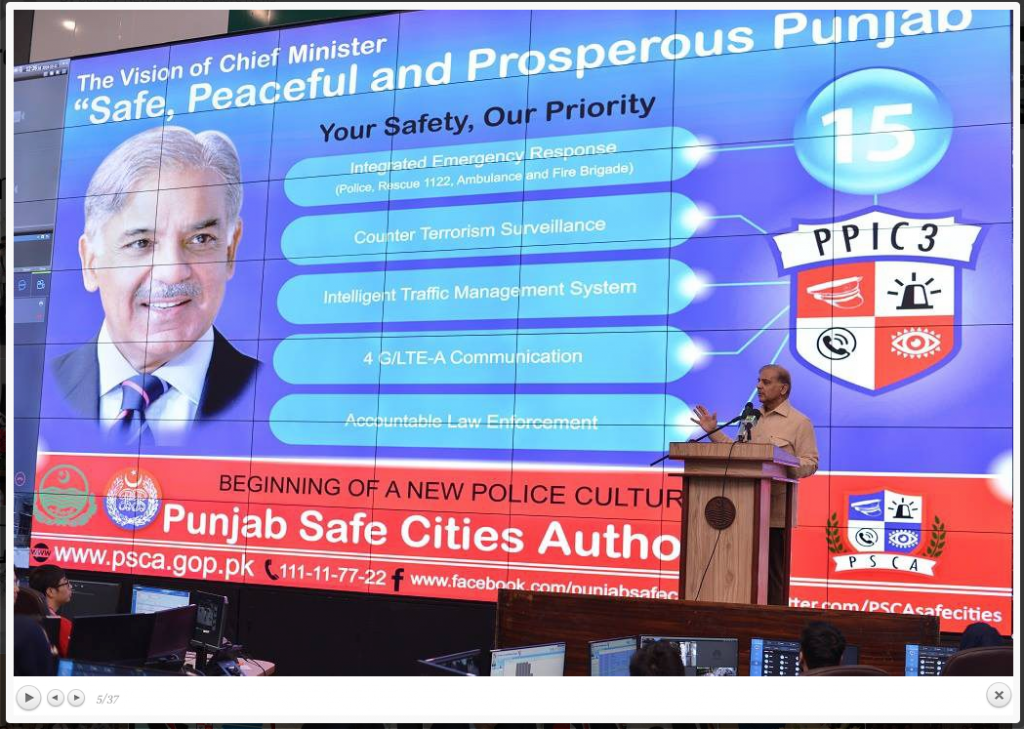

Established under the Punjab Safe Cities Ordinance 2015, the PSCA aims to bring ‘security and quality of life to today’s complex cities through the use of technology, infrastructure, personnel and processes.’ At the heart of the PSCA is an extensive network of cameras — 10,000 in Lahore and nearly 8,000 in Islamabad. These cameras are in the process of being installed across Lahore as we speak, at over 2,000 select locations, that include public institutions, crime hotspots, and city entry and exit points. They broadcast a live feed 24/7 into what is, the crown jewel of the PSCA, the swanky, and big brother-ish, Punjab Police Integrated Command, Control and Communications Centre (PPIC3).

I am taken on a tour of the establishment. For someone who has grown up in the thana culture of the eighties and nineties, the swanky setup of the PSCA and the PPIC3 is more reminiscent of a corporate office than anything else. The place is abuzz with activity. Young adults, in snappy uniforms, are taking calls, shifting cameras and living the James Bond life. The median age here is 28, I’m told. Much younger than most government institutions. And they’re all IT graduates.

For such a high-tech setup, the process is quite simple. The call from the public lands on an operator’s desk. Within seconds, the exact location of the call’s origin is traced, and marked. The operator notes the complaint or observation and then sends it forward to the dispatch centre. Here, according to the nature of the complaint, the relevant authorities are notified. This can be the counter-terrorism department, the fire brigade and/or Rescue 1122 etc. At the same time, if need be, a live feed of the location can also be brought up thanks to the camera network currently being installed across the city. And if there are no cameras available, officers equipped with the 4G handheld device can be moved to the location immediately.

At the heart of the PPIC3 is the viewing centre. One large rectangular space filled with screens. Any of the 10,000 cameras being installed across the city can be brought up on the screen with a few clicks. And although the cameras’ resolution is supposedly a mere 2 mega pixels, their ability to zoom in, into cars, number plates, and commuter’s faces is frighteningly powerful. And along with the ability to read vehicle registrations, rumour has it that a certain software is also being developed which will enable facial recognition and run it across the NADRA and other databases as well.

The PSCA has its fair share of critics: from political opponents shouting at the sheer cost of the project to rights activists accusing the government of throwing a surveillance net over the population. Yet the project has pushed on, in record time, and is now fast reaching completion.

At its helm is a Harvard graduate named Akbar Nasir Khan. He sat down with Newsline to explain the reach of the PSCA and how it would be a

At its helm is a Harvard graduate named Akbar Nasir Khan. He sat down with Newsline to explain the reach of the PSCA and how it would be a

game-changer, not only in security, but governance and city management as well.

Why do you need so much surveillance in Pakistan’s safest city?

The purpose of the Punjab Safe Cities Authority (PSCA) is not to conduct surveillance but to manage our urban centres better. Historically, there has never been any focus on public safety in Pakistan or Punjab, and security/surveillance is just one part of that. The idea behind the PSCA is to have an integrated system that caters to the growing urbanisation of Punjab and associated increase in population as well. So our cameras won’t just do surveillance. The same cameras will be used for emergency response and will also be a key component of our upcoming traffic management system as well. This is a step up from the Islamabad project where the cameras can only be used for one function. Take traffic management for example. Its direct and indirect benefits are numerous. For example, there will be fewer traffic jams, and hence people will save time, which they can either spend at work or with their families. Lesser time on the roads will also mean lesser carbon emission. So the environment will also benefit.

Can you elaborate on this traffic system?

As you know, Lahore’s traffic signals are manually operated at the moment, by traffic wardens present at the location. What we are trying to do, for the first time in the country, is synchronise our traffic signals, through algorithms and historical data of traffic flow. To do this, we have to install nearly 300 new poles across the city which will happen over the next eight months. At the moment, we’ve installed some on the Mall and we are testing them under live conditions. This testing is vital because these solutions have to be tailored to match our unique traffic system which includes so many different modes of transport, including buses and donkey carts. However, what we are trying to achieve is that for example, during morning peak hours, the main roads get lesser red lights, and the same during the evening peak hours as well. We are also looking to instal sensors which will be able to change signals according to car activity as well.

Additionally, we are also working on automatic number plate recognition, but there is some work to be done there because at the moment, the digits on the number plates aren’t large enough to be recognised by the camera. So we’re working with the excise department to come up with a format that can lead to a higher rate of detection by our cameras. This is work in progress.

So apart from traffic management, what are the other key components of this system?

We have a few key elements. The first is an integrated emergency response segment. Previously, you had different numbers for different emergencies. There was the fire brigade, it had its own number. As did Rescue 1122. And the Police was at 15. What we’ve done is bring everything under 15, since it’s a number everybody already knows. So regardless of the kind of emergency, you can get all the help you need from this one number. Counter-terrorism surveillance is another important section. We now have eyes on the ground at public spaces, where there is a lot of human traffic, and at other sensitive areas, such as the airport and the railway station. We’ve also defined 30 entry and exit points of the city, and we are now able to see who’s coming and going. And this surveillance isn’t limited to CT. For example, we have cameras in markets that have a higher percentage of female visitors, so we can respond to any harassment we catch on screen.

Another important component is 4G LTE communication. All our wireless communications will happen through this network. It’s secure and much faster than your conventional 4G network. We have 6,000 4G-enabled handsets working on this frequency. So where we do not have cameras, we have people on the ground with these handsets. And they can quickly send in a picture or a video of an event and get direction from the centre. These handsets will be distributed by the end of June next year. Plus all our police vehicles will also have cameras, working on the same network. Previously, there used to be the problem of relaying media to the centre for direction. Streaming was patchy and mobile networks unreliable. We’ve taken care of that. And since we can now pinpoint locations to four decimal points, we can clearly see where jurisdictions begin and end. So the old excuse of this isn’t in our area doesn’t work anymore either.

This is all very good, but coming back to the key need for public safety, this system is, at best, reactive?

We have become pro-active in a way, because now we don’t have to wait for the public to report an incident. Our eyes on the ground see it, and then react accordingly. Pro-activity is based on two things: one is intelligence, so that you have information you can analyse and then make predictions from it and second is that you see it before anybody else. We’ve tackled the second part first. And as we get data and analyse it, we can tackle the prediction part as well. And again, this isn’t specific to terrorism or violence. We can collect and measure traffic data as well and then make plans accordingly. Nothing is based on anecdotal evidence anymore.

There is a lot of data being produced in this system. How safe is this data? And secondly, your contractor, Huawei, has a history of leaving backdoors in the software and hardware it instals. Did that feature anywhere in your conversations?

We have numerous security frameworks in place to ensure that data is not stolen or misused. This data is off-limits to the Chinese people who have installed the systems we use. And yes, we are aware of the news regarding Huawei, but we’ve done the best that we could. Especially when it comes to the integration of data between say NADRA, or vehicle records. It is kept on entirely separate servers to which the Chinese have absolutely no access. Still, as you know, nothing is really safe nowadays.

The police has traditionally been rather averse to technology and to learning new skills. How have you overcome this rampant technophobia within the force?

This is partially true. People who joined the force 15 or 20 years ago, right after matriculation, are averse to technology. But the ones who joined after the turn of the century, they’re part of the IT revolution. They know how to handle a Smartphone, so using the hand-held device won’t be a problem for them.

Does having this system create a method of accountability within the force?

We recently saw somebody taking a bribe through a camera and he has been suspended. It is an independent unit that reports what it sees, with evidence. A majority of our force is out on the streets, so we have eyes on them as well. The system looks at everybody.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore. He is the current managing editor of MIT Technology Review Pakistan, a bi-monthly science and technology magazine.