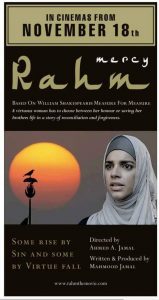

Movie Review: Rahm

By Zahra Chughtai | Movies | Published 9 years ago

It is good to see experimental cinema breaking new ground in Pakistan. One such effort is Rahm, a collaborative effort between writer and producer Mahmood Jamal and his brother, director Ahmed Jamal, with Sanam Saeed, Sajid Hassan and Sunil Shankar in leading roles.

It is good to see experimental cinema breaking new ground in Pakistan. One such effort is Rahm, a collaborative effort between writer and producer Mahmood Jamal and his brother, director Ahmed Jamal, with Sanam Saeed, Sajid Hassan and Sunil Shankar in leading roles.

Adapted from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, the film faithfully follows the plot of the original, except that the entire story is now set in the city of Lahore, with the obvious cultural and social adjustments. The lead character of the duke is replaced by the governor of Lahore (Sajid Hassan), who after a heart-attack, appoints an authoritarian new governor to rule the city in his absence and check corruption. But the acting governor (Sunil Shankar) is a hard-hearted zealot, who launches a merciless campaign against real and perceived licentiousness. Unknown to him, however, the real governor disguises himself as a faqir to mingle with his people and keep an eye on his appointee.

As the acting governor starts handing out harsh punishments, a young man who had secretly married his sweetheart, is hauled up by the moral police for having relations out of wedlock. The young man insists that the woman, now with child, is his wife, but since he cannot produce a nikahnama, he is thrown into jail and sentenced to death.

News of this calamity reaches his loving sister (Sanam Saeed), a pious young woman who is earlier shown distributing food to the needy and reciting the Quran. The distraught young woman approaches the acting governor and pleads on her brother’s behalf. The governor remains unmoved until she reveals her face. Then, smitten by her virginal beauty, he propositions her in the most crass manner — her virtue for her brother’s life.

A series of twists and turns follow, in which the film touches on religious hypocrisy, the degradation of society, the subservience of justice to the powerful…all of these themes as relevant today in Pakistani society as they were in Elizabethan England. As the story progresses, in true Shakespearean style, identities are swapped, new truths are revealed and in the end all ends well. The last scene is left ambiguous in this film, as in some other interpretations of the original, and the audience is left to make up their own minds about the heroine’s silence.

One can see what the director is trying to do here, and there is much resonance in the theme. Perhaps, of Shakespeare’s plays, Measure for Measure lacks the psychological depth and pathos of the tragedies, but it has a well-developed plot and enough complexity to justify its adaptation as a contemporary movie.

However, the problem is that when so literally transposed onto a modern setting, the characters appear one-dimensional and some of the plot twists, which are acceptable in the original, seem weak. For example, the couple’s inability to prove that they are married seems rather forced, as does the heroine trading places with the villainous governor’s abandoned wife, without his realising it.

At the denouement, the justice meted out by the governor also doesn’t fit in with modern moral sensibilities. It all seems somewhat anachronistic and forced. The audience may be expected to suspend disbelief since this is a Shakespearean adaptation, but in that case a more stylistic handling is called for with artistic merit overtaking rationality and plot progression.

To their credit, the actors have done their roles justice, with Sajid Hassan rendering a polished performance. Sanam Saeed is always a commanding presence on screen, if a tad preachy in this case, embodying the strength of virtue and pure-willed determination. Sunil Shankar is also convincingly loathsome, while Nayyar Ejaz deserves mention as a sleazy local influential. In Shakespeare’s original he provides comic relief. In this version he is the only character with shades of grey who exposes the evils of society while being a party to them, but who also helps the distressed heroine in his own way.

In the spirit of staying true to the original, director Ahmad Jamal has stayed away from song and dance or any attempt to win over a commercial audience — and rightly so. This is no Omkara, as he has repeatedly pointed out in interviews. And that is not the film’s problem. But perhaps some more subtle subversion of the text or of the medium itself was called for.

Interview: Mahmood Jamal

Writer and producer of the film Rahm, Mahmood Jamal, is a London-based author, script-writer and poet. Newsline caught up with him briefly to talk about his latest project.

You have a literary background. What made you turn to film-making?

I do have a literary background, but have been involved in film and TV in the UK for over 25 years as an independent producer. I was the writer of Family Pride, the first Asian soap in the UK.

This film was the first feature film I have written, but not my first drama. In a sense it is a continuation of my interest, which started with my book Islamic Mystical Poetry (Penguin 2009).

Why did you choose to adapt Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure?

I first saw Measure for Measure on the stage nearly 10 years ago. I was stunned by two aspects of the play: the similarities between England in Shakespeare’s time, and what is happening in the Muslim world now — the extremism, the puritanism, and the debates about punishments. And the other aspect of the play that struck me was its almost Sufi aspect: the idea of mercy and a merciful God.

This led me to follow this idea, and I decided to make a film based on it. It was after years of thinking and gestating on it that I finally got the project together with Ahmed Jamal, my younger brother, who directed the film. I decided to write the film in Urdu, though I had written it in English initially.

This film was never meant to be a purely commercial venture, and was for both Pakistani audiences and the international market.

You said you pursued this project for eight years. Why was the film so long in the making?

It takes a long time in persuading people to back a serious idea. Also, I had taken a break from work due to family commitments. Ahmed Jamal, the director and I really started work on it two years ago, creating the script and raising money to produce the film. Ahmad must be commended for doing a great job given the time constraints and limited budget we worked with. The film was shot in 27 days in Lahore.

There was barely any pre-release publicity for the film and no real premiere. Why was this so?

I think because of the subject matter, and not being a commercial type of film, our distributor did not have the confidence to award it the hype and publicity it deserved. In any case, we have learnt important lessons about the Pakistani market through all this. We wanted to give a thinking audience an alternative from the usual, and also had an eye on the international market, so we did not compromise with the story.

We will release the film in March 2017 in the UK to mark 70 years of Pakistan’s independence. It will also be the first time that Lahore will be put on the world literary and cultural map.

Zahra Chughtai has worked and written for Pakistan's leading publications including Newsline, the Herald and Dawn. She continues to write freelance.