Pilferage Pays

By Huzaima Bukhari | Economy | Published 6 years ago

“Amnesty is the forgiveness of something. Amnesty is anything that says, ‘Do it illegally. It will be cheaper and easier.’”

– Marco Rubia: United States Senator from Florida (since 2011).

Pakistan is unique in that it has various laws that protect tax evaders and criminals, facilitate the creation of assets inside and outside the country and help whiten black money through inward remittances. The rich and mighty in Pakistan, many of whom have dual nationalities or businesses abroad, enjoy full protection from probes into sources of monies/assets, under the Foreign Accounts (Protection) Ordinance, 2001, the Protection of Economic Reforms Act, 1992 and section 111(4) of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001.

Pakistan fits the profile of a “soft state”– famously articulated by Nobel Laureate, the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, in his 1968 work, Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations. It is a broad-based assessment of the degree to which the state and its machinery, are equipped to deal with responsibilities of governance. The softer a state, the greater the likelihood that there is an unholy nexus between lawmakers and law-breakers. Pakistan is a classic case of this. Since 1958, numerous tax amnesties were announced, but these failed to achieve the desired results.

Pakistan is one of the 140 countries that is a signatory to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), which defines the “offence of illicit enrichment” to mean “a significant increase of the assets of a public official that he or she cannot reasonably explain in relation to his or her lawful income.” The Convention covers many different forms of corruption, including bribery, trading in influence, the abuse of functions and corruption in the private sector. The most prominent, however, is the inclusion of provisions aimed at returning assets to their rightful owners, including the countries from where these were illegally obtained in the first place.

Gathering the necessary evidence to prosecute white-collared criminals is a difficult task in Pakistan. However, resorting to circumstantial/corroborative evidence, such as the possession of property, or having a lifestyle that exceeds legitimate income sources, can reveal enough details to bring the perpetrators to justice.

While the international community is urging member states to criminalise corruption, the Government of Pakistan is offering amnesty to those who had the audacity to pilfer the country of its vital resources without paying the due taxes on funds stashed in foreign currency accounts. The handful of honest taxpayers are the losers in this scenario, whereas those who violate laws are allowed to ‘decriminalise’ their sins through ordinances which purport to provide legal cover by payment of tax.

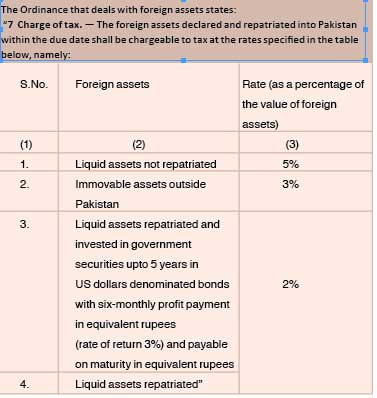

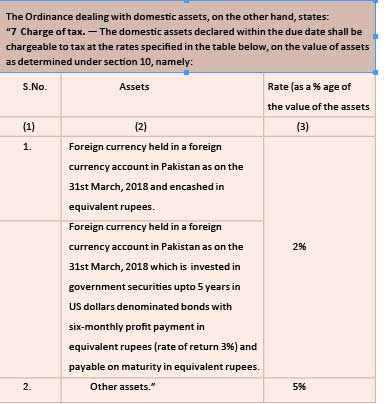

On April 5, Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi announced a five-point tax reforms package, introducing a substantial reduction in income tax rates and an amnesty scheme for undeclared foreign and domestic assets, which is valid till June 30. This tax amnesty scheme was subsequently ratified by President Mamnoon Hussain, through four ordinances: Voluntary Declaration of Domestic Assets Ordinance 2018; Foreign Assets (Declaration and Repatriation) Ordinance 2018; Income Tax (Amendment) Ordinance 2018; and Economic Reforms (Amendment) Ordinance 2018.

Opportunists and those compelled to repatriate funds without seeking permission from the government, on account of circumstances beyond their control, can avail the benefit of these schemes by June 30, 2018, unless this is extended by another notification. The most worrisome part is that the declarants are provided confidentiality.

Experts believe that this could be challenged in courts and could draw a strong reaction from international agencies fighting terror-financing and money-laundering. The Financial Action Task Force (an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1989 on the initiative of G7 to counter money laundering), has already sent a letter to the government expressing its concerns.

Two more ordinances – amending the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (the Ordinance) and Protection of Economic Reforms Act, 1992 — intend to tax concealed assets in the year of discovery rather than in the tax year to which they are related; and additionally, allowing only tax filers to deposit currency in their foreign currency accounts.

Interestingly, another amendment (which could easily have been incorporated in the Finance Act, 2018) in division I of Part I of the First Schedule of the Ordinance effective from July 1, 2018, is aimed at providing exclusive rates for an association of persons and reducing tax rates substantially in the case of individuals.

Considering that the tenure of the present government is drawing to a close, these measures seem to be deliberate. Rather than bringing the Parliament into the fold, presidential ordinances were used to do the needful. Besides, the outgoing government hopes to establish its credibility by aiming to reduce the fiscal deficit before the financial year ends, and improving its standing in the upcoming elections.

The stated motive behind the move is documentation, and not revenue generation. There is a general expectation of low repatriation not meeting the $ 5 billion target announced by Haroon Akhtar. Critics maintain that documentation could be obtained using IT tools and third-party information inside the country and taking the help of treaty networks and other international organisations as far as assets stashed outside are concerned. The main objection to the Tax Amnesty Scheme is that such an unprecedented manner of surrendering before ‘money power’ will only further weaken the country — and the economy.