Behind Closed Doors

By Ali Bhutto | Special Report | Published 7 years ago

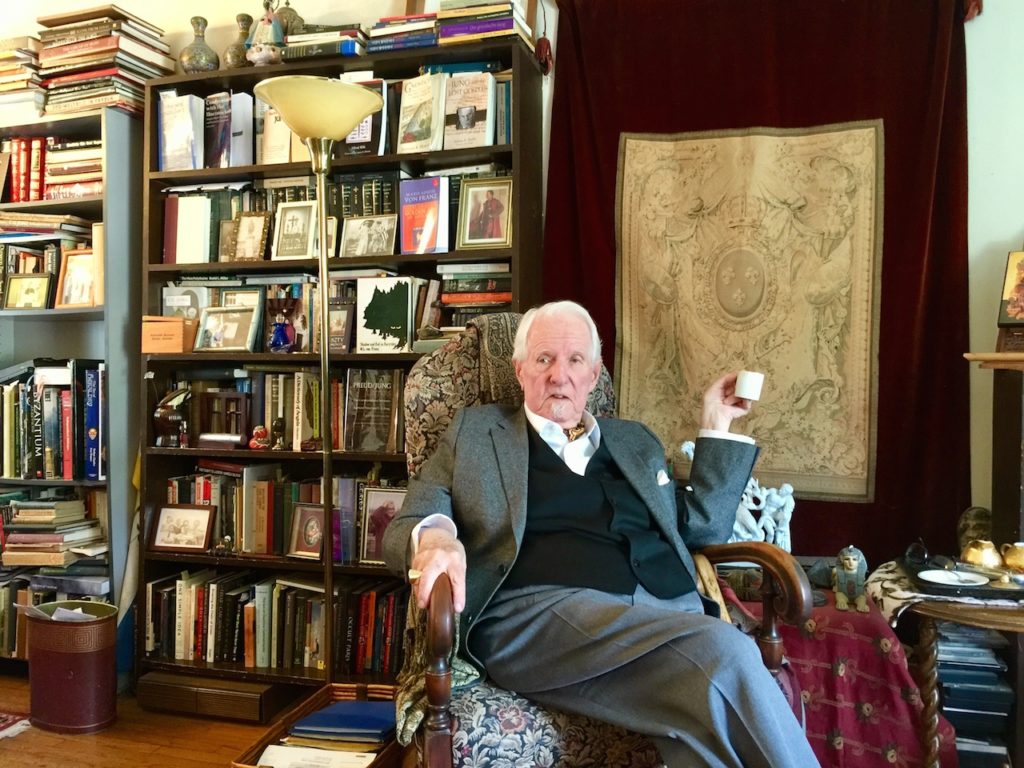

Of Hungarian descent and a Gnostic bishop, he is an author and incumbent President of Besant Lodge in Los Angeles. The name is Stephan — pronounced Stephaan — Hoeller. The eyes, half-closed, look neither up nor down, but see everything. And despite his advanced years, the bearing is sturdy. He holds his cup of coffee at a tilt. This may look like a mannerism, but it may also be because his grip is not quite firm. Tellingly, the initials ‘S.H.’ are embroidered on the cuffs of his crisp shirt.

Stephan hands Winter Lazerus, fellow theosophist and property manager at Besant Lodge, a letter he received in the post. “God knows what it means,” he says, amused by its cryptic content. Lazerus proceeds to examine the note and its accompanying talisman — an aboriginal woman holding a wand.

I pray you understand. I can only hope to sit with you again over eggs and beacon. The time is now.

1. Fix a tall drink,

2. Listen to the next song,

3. Remember,

4. The gift is yours so tear it open.

Love,

H E S

On an enclosed page torn out of a dictionary, the word ‘wizard’ is underlined.

Lazerus, clad in all black and sporting a pony-tail, cuts a tall, shadowy figure. He lives in an old cottage behind Besant Lodge. This is the quaint and leafy neighbourhood of Beachwood Canyon. It is the home of Stephan, Lazerus and the Theosophical Society. It is also home to the sprawling Hollywood sign — an intruder in this quiet part of Los Angeles. But the Society predates Hollywood — cinema was a comparative latecomer in these parts.

“The theosophists came to these hills because they believed that the spiritual and creative energy was strong here,” explains Stephan. And so in 1912, Albert Warrington and his associates founded the hamlet of Krotona — the society’s first national headquarters. The colony, located up the hill from Besant Lodge’s current location, is a collection of Moorish structures that have been converted into apartments. “Dora van Gelder Kunz, a former president of the Society, writer and famous clairvoyant, also believed that there was an angelic energy present in this particular part of Southern California,” continues Stephan.

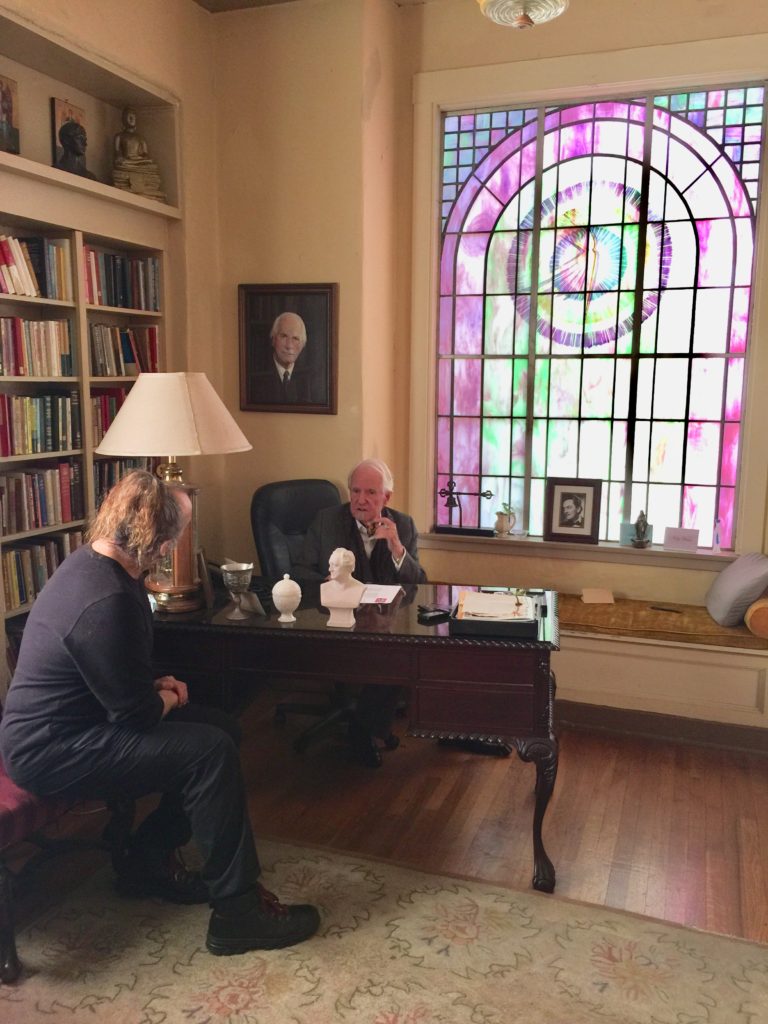

The Lodge’s stained glass windows give its interior a church-like quality. They display the celestial symbols illustrated in theosophical teacher Geoffrey Hodson’s The Kingdom of the Gods. “Many think that this building was part of the old colony of Krotona,” says Stephan, “but that is not the case.” It was in fact a neighbourhood movie theatre, built in the early 1920s. “The first silent film theatre in Los Angeles,” Lazerus proudly adds. His cottage, even older, was once a bookshop. The Society bought both properties in 1954, while Stephan was on the board of directors.

Winter Lazerus (L) and Stephan Hoeller at Besant Lodge. (Photos by Ali Bhutto)

This easternmost tail of the Santa Monica Mountains has always lured theosophy into its fold. Although Krotona relocated to Ojai owing to financial difficulties during the Great Depression, the Society returned in the incarnation of a rented facility near Beachwood Canyon before acquiring its current location. The commune in Ojai, now the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, is a thriving centre of research and spiritual learning.

Unlike many residential areas of Los Angeles, “there is a sense of community here, in Beachwood Canyon,” says Lazerus, “a real sense of the old part of L.A.” To locals, Besant Lodge is a community centre of sorts. Universal brotherhood is a central tenet of the Theosophical Society — as is scientific, philosophical and mystical inquiry, open to all religions and bound by none. Theosophists believe an ancient wisdom underlies all creeds. They seek to access a higher spiritual plane, through meditation, intuition and the study of theosophical literature.

“The Los Angeles chapter has about 20 to 30 members,” says Stephan. It hosts lectures, classes, readings, joint activities with the Gnostic Church, and has “offered Spanish lessons for the last 20 years.” Further west, in the winding lanes of Bel Air, lifeless mansions gaze coldly at passing cars. Beachwood Canyon, however, has a soul. A nameless canyon and remote farming community in the 1880s, it became the site for an ambitious yet short-lived housing project — Hollywoodland — in the 1920s. “We border the largest municipal wilderness preserve in the world, where mountain lions roam,” says Lazerus, referring to Griffith Park.

Stephan produces a rare photo of Annie Besant, a leader of the Indian Independence movement and one of theosophy’s most influential figures. She is about to board a Goliath airliner with Charles Blech, general secretary of the Theosophical Society in France, and an unnamed gentleman. On the Lodge’s wall hangs the charter of Krotona, bearing Besant’s signature. It is dated 1920 — the year she visited the colony, as the Society’s international president.

Besant delivered a series of international lectures that inspired the opening of various chapters, including the one in Karachi, in 1896 and in Hyderabad, Sindh in 1901. “We are all renegades here,” says Hamid Mayet, General Secretary of the Karachi Theosophical Society and President of the Theosophical Order of Service, Pakistan. Having defied social norms and challenged the status quo for much of his life, Mayet is the best man for the job. Beneath his casual, easy-going demeanour lies a steely resolve.

The chaos of M.A. Jinnah Road is muted inside the chapter’s library. Leather-bound volumes of the first edition of Helena Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine line the shelves. Jamshed Memorial Hall — home of the Karachi Theosophical Society — is a nostalgic byword for many a Karachiite. It is a relic of a more enlightened period in the decaying city’s lifeline. Today, however, the Society maintains a low profile. Mayet moves across its corridors with the air of a man who has broken free of the baggage of tradition.

Hailing from an affluent Indian family of Johannesburg, Mayet grew up in South Africa during Apartheid. “Within the Indian community itself — whether it was Hindus or Muslims — there was discrimination against blacks and a pronounced class inequality,” he recalls. “I found it all very hypocritical; attitudes seemed to contradict the religions that were so ardently being followed.”

Mushtaq Jindani (L) and Hamid Mayet.

Inspired by anti-Apartheid leaders such as Dr Yusuf Dadoo, chairman of the South African Communist Party, Mayet started rebelling at a young age and became a conscientious objector. At the age of 16 he joined the youth wing of the Pan African National Congress. “In my heart of hearts, I was trying to identify with the common man,” he says. “I felt embarrassed that I was from a well-off family, when all around me there was racial and economic inequality.”

Stephan, an aristocrat, also struggled against oppression in his early years. When a Soviet-style communist regime consolidated power after the Second World War, his family lost all their property and lived in great need. He left Hungary, arriving in the US in 1952. “The Nazis had destroyed a lot of theosophist literature during the war, and subsequently, so did the communists,” says Stephan. “Totalitarian governments do not like organisations such as the Theosophical Society.” At first, Stephan dreamt of becoming a Catholic priest. And although he was 15 when he first heard of theosophy, it wasn’t until his arrival in Southern California that he joined the Society.

In Pakistan, theosophists prefer to remain below the radar. The Karachi Theosophical Society’s website doesn’t give away any names. The fate of Dara Mirza, a former chapter president, is testimony to the darkness that engulfs the city. Mirza’s portrait hangs beside those of Blavatsky — co-founder of the Theosophical Society — and Jamshed Nusserwanjee, a former president of the Karachi chapter and the city’s first mayor. A descendant of Sindhi literary scholar Mirza Kaleech Baig, his ancestors migrated to Sindh from Georgia in the mid-nineteenth century. He was the president of the Society for over three decades, until September 14, 2007, when his body was found in Mauripur, Karachi. He had been kidnapped on the way to work earlier that day. The episode remains buried in a deafening silence.

“Gool Minwalla was concerned that the Muslims’ suspicions of other religions would one day become a problem for their own countries,” says Stephan. “She was a fine lady,” he says of the former president of the Society, whom he had met in Ojai in the early ’80s. According to Stephan, it was during Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s tenure that religious intolerance first surfaced in Pakistan.

“Dara Mirza, a learned man, had a strong grasp of esoteric philosophy,” says Mayet. The Esoteric school focuses on accessing the higher spiritual plane — described in theosophical texts as “the unexplained laws of nature and powers latent in man.” According to Mayet, the previous generation of members, such as Amir Ali Hoodbhoy and Hatim Alvi, carried out a deep study of theosophical literature. The current membership of 50, however, gravitates towards the Theosophical Order of Service (TOS) — a social services wing.

The ever-expanding Montessori at Jamshed Memorial Hall provides underprivileged students with a quality education at a fee of Rs 1,700 a month. Nusserwanjee and Minwalla felt that Italian educator Maria Montessori’s emphasis on creative and independent thinking had much in common with the values of theosophy.

The theosophists of Karachi are currently working towards opening a Montessori at the Besant Lodge in Hyderabad — a structure that Mayet describes as being “far more impressive than ours.” After the demise of the Lodge’s president — the renowned scholar and political activist Ibrahim Joyo in 2017 — membership has dwindled. A member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement, Joyo’s controversial work Save Sindh, Save the Continent — From Feudal Lords, Capitalists and their Communalism, published in 1947, resulted in the termination of his teaching post at the Sindh Madressa. Joyo was not the only theosophist to find himself at odds with the Madressa. A few decades earlier, Hatim Alvi, a student at the institution, was expelled for writing an article critical of the British rule.

Besant Lodge, Hyderabad. (Photo courtesy: Karachi Theosophical Society)

“The Theosophical Society attracts people who tend to think out of the box,” says Mayet. “It has nothing to do with political orientation. Nor are we a religious organisation. This is a society that promotes unity.” He says it was Joyo’s interest in Sufi culture that made him gravitate towards theosophy. “Sufism is closer to esoteric philosophy.”

“If you want to find God, you can find him in the garden,” says Mushtaq Jindani, Joint Secretary of the Karachi Theosophical Society and Director Education, TOS. “You can cultivate God in the garden.” Jindani heads a small club called The Linkers, a group of people interested in mind sciences — the kind that deal with spirituality in relation to the mind and body.

When Stephan first joined Besant Lodge 60 years ago, there were over 100 members. The current membership is only a fraction of this, owing to the existence of numerous other spiritual organisations. The Karachi and Hyderabad chapters have suffered a similar fate with regard to membership, especially during Partition.

Mayet is doing his best to make the Karachi chapter sustainable, so that he can hand it over to the next generation in working condition. “It has existed for over a hundred years, and I want it to be there for another hundred,” he says. Similarly, Stephan — in what seems like a valedictory remark — emphasises the need to reconnect the “threads” that link theosophical societies across the globe.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com