A Beacon for the Blind

By Deneb Sumbul | Health/Medicine | Published 7 years ago

Childhood blindness: The most common causes are malnutrition and trauma.

One of the largest non-government organisations working across Pakistan in the field of eye care, the Layton Rahmatulla Benevolent Trust (LRBT) recently reached its 38 millionth milestone: restoring the sight of a 10-year-old legally blind patient named Sher Muhammad. The story of this young boy is but a minuscule sample of the impact LRBT has made in the lives of millions of patients over the last 32 years.

The son of a construction supervisor from a small town in Sukkur, Sher’s vision, hazy since early childhood, had deteriorated to the point where he could barely see. His parents had explored all the ill-equipped hospitals and clinics in Sukkur, which were unable to make the correct diagnosis. Meanwhile Sher suffered from dejection, falling behind in school, getting reprimanded for lack of attentiveness and interest. His parents and four siblings tried their utmost to help him cope, but the minutest tasks became a monumentous struggle as his mobility became increasingly limited. Finally, when work brought Sher’s father to Karachi, he discovered the LRBT and the free eye treatment it offered.

Sher was diagnosed with corneal opacity in both eyes — a treatable condition that requires a corneal graft. A donor was arranged from abroad, since there were no local cornea donors in Pakistan. After surgery, Sher recovered sight in his right eye and he returned to his school in Sukkur, where his headmaster and teachers, having become aware of his problem, were more sympathetic towards him. And he will be returning for a corneal graft in his left eye soon. The surgeon who performed the procedure recalls the young boy holding his hand and telling him as he left the hospital after his first graft, “Thank you so much. You’ll see one day I will become a doctor like you and help others.”

The number of blind or visually impaired people in Pakistan is estimated to be 11 per cent of the population — ie approximately 23 million people, of which three million are children. The 2.1 million who are blind cost the national exchequer Rs. 69 billion (or US$ 700 million) in terms of lost productivity. With two-thirds of the population earning less than US$ 2 a day, food takes away 60 per cent of their earnings, making treatment unaffordable. Unsurprisingly, the prevalence of blindness is thrice as high among the poor versus the affluent, but remarkably, 80 per cent of the blindness is curable.

The crux of LRBT’s mission since its inception has been, “No man, woman or child should go blind just because they cannot access or afford the treatment.” This was the cause the two co-founders, Graham Layton and Zaka Rahmatulla, decided to espouse when they launched the Trust in 1984, after they concluded that by helping the blind and restoring the sight of the visually impaired, they could make them productive members of society again.

Graham Layton was a British ex-army officer and a construction engineer. He was the head of a construction company called MacDonald Layton Company, which was involved in major construction works in Karachi and Islamabad. Zaka Rahmatulla, the other founder, was the CEO of Wazir Ali Industries. Both men were very close friends and both retired at the peak of their careers. After retirement, Layton decided to settle in Pakistan, giving up his UK citizenship.

Sher Muhammad – LRBT’s 38 millionth patient.

Zaka Rahmatulla was blind in one eye and understood the issues faced by the visually impaired. At the time the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a report that said curing blindness was the tenth most effective medical intervention in the world. The report also stated that with a relatively small amount of money, in the case of curable/reversible eye diseases, it was possible to give a visually impaired person his sight – and in doing so, his life. The blind in poorer countries tend to have a relatively short life span, mainly because they are dependent on others, and in worst case scenarios, are reduced to begging.

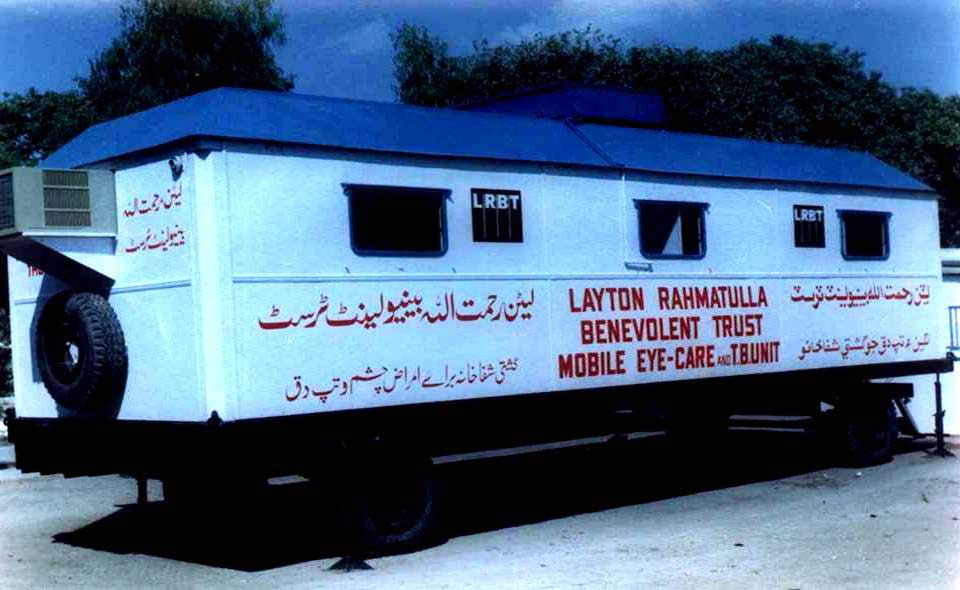

Each co-founder contributed $33,000 dollars, about five lakh rupees at that time, as seed money, and started with a caravan equipped with an Out Patient Department (OPD) on one side, a pharmacy on the other, and an operation theatre in the middle. They had it towed to Tando Bago, a small, remote town in Sindh, where the people, many of them haris (peasants) lived in depressed conditions. When the LRBT initiated its eye-care work, the patients would sleep in tents on charpoys. In the very first year in this small village, LRBT treated more than 11,000 patients, and performed 550 surgeries, while the construction of their purpose-built hospital for the town was simultaneously underway. On completion of the hospital in 1985, the caravan was towed back to Karachi and it became a blueprint for several other LRBT hospitals, that were to follow.

LRBT’s first eye care facility in 1985 was a caravan operating in Tando Bago in Sindh.

Thirty-two years later, the LRBT boasts the largest network of purpose-built medical facilities: 19 hospitals, 52 family eye-care centres, and four outreach centres across Pakistan. Patients are managed through a three-stage system and the lowest part of the pyramid is primary eye care. For easy access for patients, the 52 primary eye care clinics are usually located within the radius of 50 kilometres of towns and villages, and are manned by qualified optometrists and ophthalmic technicians who do refraction and attend to basic eye ailments like allergies or conjunctivitis.

People who require more complex eye treatments are referred to the nearest LRBT hospital. In remote places like Thar, patients are bussed to the nearest eye hospital for surgeries at LRBT’s cost, in this case the Tando Bago Hospital. The second level of the pyramid are the 19 secondary eye hospitals which cover 70 per cent of the Pakistani population. These hospitals are located in such a way that anyone can reach them by bus within two hours. Secondary hospitals treat all eye problems except for cornea transplants and retinal surgeries, and also attend to rudimentary paediatric care.

Out of the 19 hospitals, two are state-of-the-art tertiary hospitals in Karachi and Lahore, that cover the full spectrum of eye care — from simple eye refraction to advanced treatments and procedures, such as retinal services, cornea transplants, diabetic retinopathy, orbital surgeries or paediatric eye surgeries under specialised doctors. “In fact, our chief surgeon is a retinal surgeon — one of the best in the country,” says Honorary Chairman, Najmus Saquib Hameed.

He continues, “These tertiary hospitals are not only centres of excellence; they are also teaching hospitals in ophthalmology. We run two-year MCPS membership programmes and four-year FCPS fellowship programmes that are recognised by the College of Physicians and Surgeons. It’s a combination of the classroom and practice and the students work in these hospitals on a salary. We also teach ophthalmology to third and fourth year medical undergraduates from the Jinnah Medical College Hospital in Korangi. We have had an association with them for the last 11-12 years.”

The LRBT purpose-built, state-of-the-art tertiary hospital in Korangi caters to more than 1500 patients per day.

In addition, the LRBT has four outreach centres, in Turbat, Gwadar, Khewra and Sibi respectively, where they have OPDs and perform surgeries once a month, using the facilities of another hospital. These outreach centres — three in Balochistan and one in Punjab — have been selectively located in remote areas where there is extreme poverty.

The LRBT’s tertiary eye hospital in Korangi also began operations in a tent, and is now an example of patient and hospital management. A relatively new OPD complex was added six -seven years ago at the behest of a donor family, which now caters to 1500 patients per day. Despite teeming with patients, it does not have the same chaotic environment one witnesses in Karachi’s public hospitals. The patients and their attendants here are seen calmly waiting for their turn in an orderly manner. Those requiring treatment go through the OPD where there are set protocols which include not only eye check-ups, but also tests for glaucoma. Around 30 to 35 per cent of the patients come for glasses and are directed to the opticians, where they are given prescriptions, and then they are on their way.

Then comes a broader area of diagnosis at the next level in general ophthalmology: depending upon diagnosis, the patients are made to undergo further tests and/or treatment as needed. For specialised problems such as at the back of the eye, or diabetic eye-related problems, patients are given an appointment for the third level, which consists of further diagnostics and eight sub-specialty clinics, where specialist eye doctors treat patients for diabetic retinopathy, surgical retinas, chroma, etc. The hospital accommodates 96 beds. “We perform 100 major surgeries daily just at this one hospital. And we have 18 other hospitals performing surgeries,” says Dr. Fawad Rizvi, chief ophthalmologist at the Korangi, Karachi hospital, who has been working at the LRBT for the last 18 years. “Through this three-tier system we can manage and filter between 1500-1600 patients a day.”

While there has been only incremental improvement in overall government healthcare in Pakistan, the LRBT has been expanding its network across the country, treating 36 per cent of all eye patients in Pakistan. The Trust adheres to the highest standards, not found in most hospitals in the country. For instance, it meets standards set by the WHO for a good surgery – ie. seven percentage points – which is considered outstanding — and for visual recovery through surgery, such as in the case of cataracts, regarded as the most common form of blindness in this part of the world. The standards laid down by the ICHS — the International Centre for Eye Health based at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) –sets the bar at 90 per cent. LRBT’s success rate is 97 per cent.

There are eye diseases that are endemic and there are others caused by the general problems faced by the Pakistani community. Pakistan is one of those countries where environment-induced cataracts should have been controlled by now, but that is not the case. While it is an aging disorder, prevalent everywhere, in our part of the world where the sun shines brighter and there is more exposure to its harmful ultraviolet rays, especially in the southern parts of the country such as Sindh’s coastal areas, and where outdoor labour is a way of life, its fallout is evidenced by the statistics. An estimated 6.8 million in Pakistan have cataract.

Cataracts and corneal blindness are, however, among the curable eye diseases. Glaucoma and retinal myopathy, meanwhile, are natural degenerations that can be arrested but not cured. LRBT introduced a Glaucoma Screening programme in 2006 for anyone aged 35 or above visiting their hospitals, after a National Blindness survey identified the disease as one of the leading causes of blindness. Since then more than seven million people have been screened. Those diagnosed are either put on eye drops, or are operated upon so that the disease doesn’t progress any further.

LRBT has also started a project in the tertiary hospital in Korangi for diabetic retinopathy. The mindset behind this project is that prevention is better than cure. Pakistan has a significant diabetic population of five per cent, of which 30 per cent develop some sort of diabetic-related eye problem. This specifically applies to patients who have had diabetes for five years. The disease eventually affects every system in the body, and if not caught on time, a person can lose his sight. About four to five per cent of the patients visiting LRBT show signs of the disease.

Of the total patients who come to LRBT, 10 per cent are children of ages 14 and below. One of the most common causes of blindness among children in Pakistan is malnutrition — particularly a Vitamin A deficiency and/or trauma. Malnourishment stretches across the country, affecting large swathes of the population, especially children. Vitamin A is fat-soluble and present in foods such as fish and eggs, which the poor generally find unaffordable. Night-blindness, caused by Vitamin A deficiency, is largely a familial problem like glaucoma.

The second most common cause of cataracts in children is trauma. Children working with heavy machinery, or working in unhealthy environments without protection are more prone to accidents. And even playtime can prove hazardous, leading to blindness among children. This can result from children in factories playing with objects like screwdrivers, or accidentally poking, or being poked in the eye with a pencil or a sharp-edged compass in a classroom. And such accidents become more common nearing Eid, when children, including those among the well-to-do, buy toys or pellet guns to play cops-and-robbers, sometimes causing eye injuries. These are unnecessary accidents, but which thankfully are preventable.

Environment plays a role in eye infections — particularly air-borne eye infections that become frequent during summer, especially in Karachi. Others are water-borne, prevalent all year round due to a lack of clean water. And in the Northern Areas, eye-related allergies are more common.

A disturbing discovery from the conversation with Dr. Rizvi and Hameed was concerning the severe eye infections caused by the misuse of coloured contact lenses that may lead to corneal blindness. These disposable lenses — aesthetic enhancement rather than a necessity — are supposed to be worn only for a short time and then discarded. However, the tendency for people is to use a single pair of coloured contact lenses for months, even years, causing risky corneal problems — a major issue among young girls. The fault also lies with the sellers who don’t warn customers about the danger of long-term use of these fashion eye lenses. And then, there are the current levels of pollution, which can exacerbate eye problems.

LRBT has performed more than 3.8 million major and minor surgeries for free since its inception.

The bulk of the donations to the LRBT — ie. about 80 per cent — are domestic, while 20 per cent comes from the diaspora abroad, says Hameed. The Graham Layton Trust — LRBT’s sister charity in London set up by Graham Layton — is the LRBT’s second-biggest donor, with Sightsavers, also known as the Commonwealth Society for the Blind, a grant-giving organisation and the biggest eye charity in the world, being the LRBT’s largest donor. With the Queen as their patron, most of Sightsavers’ work is in Commonwealth countries, but they have also expanded their outreach to other countries. Most of the LRBT’s funding comes as zakat from individuals. In 2016-17 for example, 62.7 per cent of its donations came from private individuals — this apart from what the larger patrons contributed. The LRBT also raises funds through zakat campaigns, fund-raising events, and donations from the Bait-ul-Maal, while about five per cent of the funding comes from the government.

Presently, 36 per cent of all eye patients that visit eye clinics and hospitals in Pakistan, end up at the LRBT facilities for treatment. The Trust’s network of hospitals perform 27.4 per cent of all eye surgeries in the country, with cornea transplants probably topping that list. Last year the 75 LRBT facilities performed 270,000 odd surgeries, including 278 corneal transplants in Korangi’s tertiary hospital and 261 in Lahore. Such procedures are now being done in the LRBT’s Quetta hospital as well.

Having found a space in Chiniot General Hospital two years ago, LRBT has started treating 150 to 200 patients per day in Chiniot, while waiting for the completion of their purpose-built hospital due to be operational this year. On completion they expect the volume of patients to increase to 300-350 per day, or even more. And the LRBT is also in the final stages of fundraising for a new hospital in Rahim Yar Khan which, when ready, will become their twentieth hospital.

Before LRBT embarked upon its mission in the 1980s to serve the blind and the visually impaired, 1.78 per cent of the total population suffered from blindness and another 18 per cent suffered from some kind of impaired vision. A survey taken five years ago showed that this figure had halved to 0.9 per cent, while those with impaired vision had shrunk to 10 per cent. The reduced numbers can be credited to the work done by assorted eye charities in Pakistan, with the LRBT meriting the highest mention.

Ironically, although the government awarded the LRBT a shield, acknowledging its tremendous work and contribution, it does not extend tax exemptions to the free Trust tertiary hospital in Korangi. LRBT is charged the full commercial rates for property, gas and water taxes. A couple of years ago, the KESC extended the charity free electricity, interestingly only after it was privatised. Prior to that, the electricity was also charged at full commercial rates.

“We need 1.1 billion rupees per year to cater to all the patients in all our facilities. Our costs go up by 8 to 10 per cent per annum – part of it due to patient volume increasing, and part because of inflation. The 1.1 billion annual expenses do not include capital expenditure.”

Three-four years ago, the burgeoning costs of the ever-increasing volume of patients, led the charity oranisation to request patients not eligible for zakat to purchase their own lens for cataract surgery. Prior to that it was a free hospital, with all services and procedures being provided totally gratis.

Pakistan is one of those countries that are signatories to the WHO’s 20/20 programme, which states that by the year 2020 at least those causes of blindness which can be reversed, like cataracts and corneal blindness, should be eliminated across the world. “At the moment we have a very huge burden of blind patients who can be cured simply by having cataract surgeries,” says Dr. Rizvi.

Unfortunately there is a huge resistance to cornea donations, or any other organ donation in Pakistan. Edhi was severely criticised for donating his corneas and SIUT faces a similar issue with regard to kidney donations. LRBT’s chairman, Hameed, emphasises, “There is no restriction in Islam on organ donation. It’s more a cultural problem than anything else. In many Muslim countries, for example Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, even Saudi Arabia, there is organ donation, and quite a lot of it.” Several fatwas have been given in favour of organ donation, such as by Al-Azhar, Sunni Islam’s most prestigious university. In August 1988, The Scientific Council of the Islamic Fiqh Academy in Jeddah authorised organ transplants, provided it was a voluntary donation and not a commercial transaction .

To meet the shortfall of corneas, the LRBT has distributed donor cards, but the resistance persists when it comes to families who are reluctant to allow the harvesting of their deceased relations’ eyes. Currently, the LRBT’s biggest source of corneas is the Pakistani Associations of Physicians in the USA, which has a cornea group. This group regularly arranges top quality cornea tissues, and raises the money required to send them to the LRBT free of charge.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.