Heritage: Saving Sethi House

By Shanaz Ramzi | Heritage | Published 9 years ago

Some of the country’s most prized national treasures would have been lost to posterity, had people with vested interests been allowed to have their way. It was through the efforts of a few enterprising women that some national monuments were wrested away from the clutches of the builders’ mafia. Among others, Flagstaff House and the Hindu Gymkhana were on the verge of being demolished, when architect Yasmeen Lari stepped in and had the sites notified.

More recently, Farida Nishtar’s efforts led to the rescue of Sethi House, a magnificent haveli in Peshawar’s fabled Sethi Mohallah, under threat of being sold to commercial builders.

The Sethi houses are regarded as the epitome of Peshawar’s traditional architecture. Farida Nishtar, niece and daughter-in-law of Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar — Quaid-e-Azam’s confidante and a former governor of the Punjab ¬ decided to intervene when she learnt that plans were afoot to sell this unique gem in the heart of Peshawar and eventually bring it down.

At first glance Nishtar strikes you as a housewife whose mission in life is to bring up exemplary children and maintain a beautiful home. But there is more to her than meets the eye. She is an artist who takes painting seriously. But it is not just her artistic streak that makes Nishtar stand out. Armed with a double masters — in Zoology and English Literature — and an aesthetic eye plus tons of determination, Nishtar seems to have taken it upon herself to safeguard the culture and heritage of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

She began with Nishtar Hall, which was established as a cultural and music centre in Peshawar in 1985, but fell into a state of disrepair when it was closed down by the ANP government. Nishtar, who is a founding member of the Peshawar Floral Club, says, “I had to find a place to hold our floral shows and since my brother had just become the governor of NWFP, I convinced him to open the premises for us. The place was a disaster — there were cobwebs all over, the seats in the auditorium were broken and the whole place bore a shabby, dilapidated look. In just 18 days, we revamped it and brought it into running condition.”

The reopening of Nishtar Hall perhaps cemented her determination to intercede when she heard that Sethi House, one of the nearly one dozen or so richly endowed mansions remaining of the original three dozen historical houses in Sethi Mohallah, was also being sold. She says, “During the British Raj, no tribal lord was allowed to buy property within the city, as they knew that heritage sites would be sold by them to make a quick buck. The ornamental havelis (mansions) that have been sold in this mohallah till now, have unfortunately all been converted into ugly concrete structures. I was born and grew up near Sethi Mohallah as my grandfather’s house was close by. I have vivid memories of the splendour of the old buildings. A unique feature of Sethi Mohallah are the numerous bazaars in the area. There is one selling just topis, another selling khaadi fabric, a third selling guns, still another selling spices, and so on.”

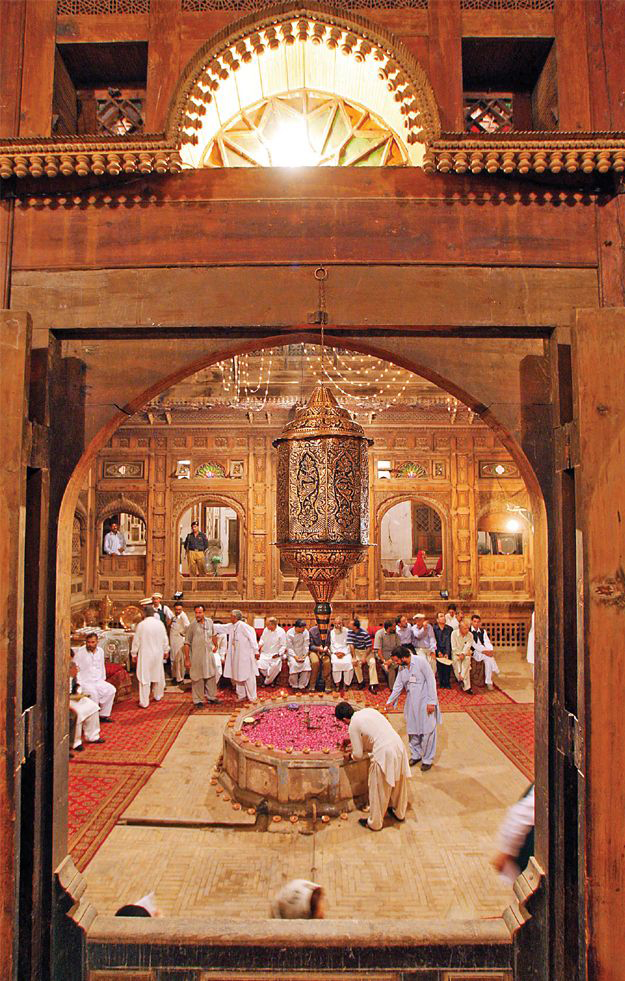

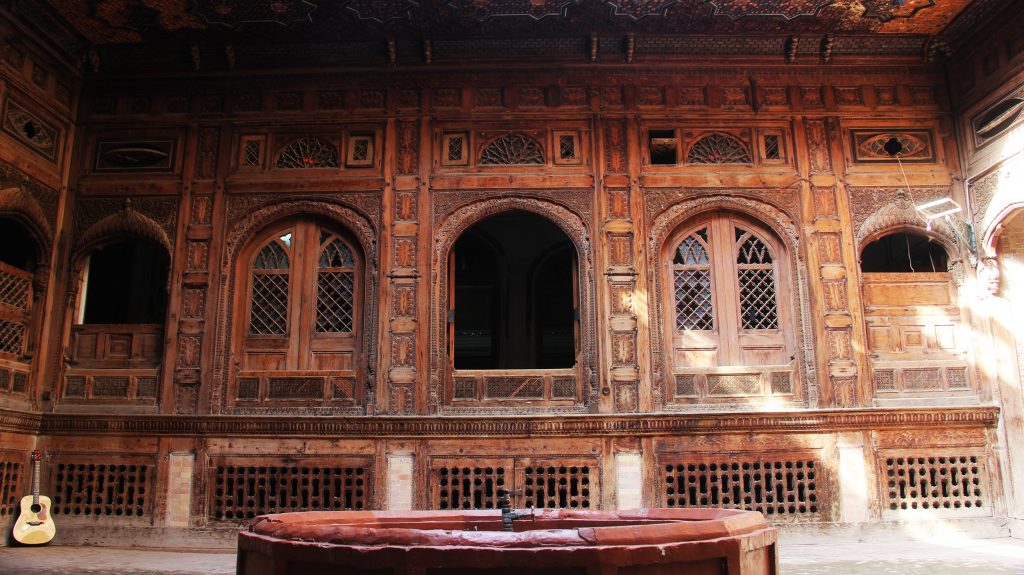

Yasmeen Lari writes about Sethi Mohallah and its significance in one of her books: “As the name indicates, the entire precinct was named after the Sethis — the wealthy — who dominated trade in the city during almost the entire 19th century. It was clear that all those who occupied the beautifully ornamented houses with exquisite facades belonged to the same family, and were thus similarly blessed not only with wealth, but also with artistic sensibility. So much so that each strove for architectural splendour equally in the treatment of internal spaces as also with outward magnificence, creating an urban environment par excellence that harked back to tradition and artisan skill, perhaps never seen before or since.”

Recalls Nishtar, “After nana passed away, my trips to the inner city became few and far between. I went back to the area only when my children were getting married as we had a lot of visitors from abroad and I thought there would be no better place to show them than the magnificent Sethi Mohallah where Sethi House had been converted into a school. They loved to visit such historic sites. However, when I went there I discovered to my horror that there was no sign of the school anymore and the beautiful haveli had been converted into a warehouse of sorts.”

Nishtar learnt that when Mr Sethi died, his property had been divided among his children. The portion that had been converted into a school had gone to one of his daughters, as it was the zenana (for females only) portion of the house. Now, this lady too had passed away, and her three daughters who had inherited the place had decided that they would sell it, as two of the siblings didn’t live in Peshawar and felt they couldn’t take care of it any more.

Says Nishtar “When I went to Sethi House, I met Meena, the third daughter, who was living in one portion of the house, and she informed me that they had decided to sell. I was very upset and could not think of anything else. When I mentioned what I had learnt to a friend, Ursulla Ansari, a German lady who lives in Karachi, she too became very concerned and suggested we try and convert this amazing historical structure into a club, as is often done abroad. But the people she discussed this with immediately discouraged her, warning that a foreigner coming up with such “preposterous ideas” in a Taliban zone was likely to get killed. Undaunted though, she asked me to get in touch with someone who knew Yasmeen Lari, and to seek her help as she was renowned for safeguarding historical buildings under threat of being demolished.”

Desperate by now and afraid that the building would be grounded before she could contact Lari, Nishtar approached a bank to step in and buy the building for their use. The bank surveyed the premises, but they rejected its location as they felt the inner city was not suitable for them. She then approached the private sector, only to face disappointment no matter where she turned.

Nishtar finally made a breakthrough. Lari responded to her with a detailed letter, enumerating all the reasons why she felt Sethi House should be saved. Nishtar was ecstatic. “I made that letter my base and went to meet the additional chief secretary KP, Ghulam Dastgir. I gave him various suggestions regarding what we could do with this historically important building. If the government bought it, it could turn it around and make it a lively tourist attraction. For instance, I told him we could have parking near Gor Khatree and take tourists on tongas to the haveli, which we could refurbish retaining its old-world charm and authenticity to give visitors a guided tour of the rooms, complete with a qehwakhana and dastarkhwan for guests to partake of meals in the traditional way. He liked my ideas and heard me out. I gave him Yasmeen Lari’s letter, which I had held onto as my trump card. He read it and disappeared into an adjacent room and returned saying, “I will talk to the chief minister; you don’t have to worry about it. I will pursue it.”

She remained in constant touch with him on the phone since then, sometimes she suspects, much to his irritation. Nishtar kept a tab on the progress or lack thereof, till one day she heard from her husband, a practicing doctor at the time, that a patient had informed him the mansion was up for sale once again, in spite of his wife’s efforts. Devastated, she went over to meet the gentleman who had been given the task of selling the premises and pleaded with him to wait a while as she had been promised that the government would step in. Luckily, he obliged.

She remained in constant touch with him on the phone since then, sometimes she suspects, much to his irritation. Nishtar kept a tab on the progress or lack thereof, till one day she heard from her husband, a practicing doctor at the time, that a patient had informed him the mansion was up for sale once again, in spite of his wife’s efforts. Devastated, she went over to meet the gentleman who had been given the task of selling the premises and pleaded with him to wait a while as she had been promised that the government would step in. Luckily, he obliged.

“And then, lo and behold,” Nishtar cannot contain her excitement as she recalls that day, “ I got a call from then chief secretary KP, Ejaz Qureshi, informing me that the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government had purchased the haveli. I promptly called up the newspapers to break the news to them.”

Finally, through Nishtar’s relentless efforts, and the timely intervention of the government, this unique haveli had been saved. The documentation work on it is complete, as is the restoration work on the overall structure, stabilising and water-proofing. Over the years, the Sethis had fallen into dire financial straits and could barely afford the maintenance of their property. With the funding that was received, only two of the rooms of the haveli could be repaired, along with treatment of the stucco walls adorned with frescoes. The remaining rooms are waiting to be restored to their original glory, subject to further release of funds.

Will wisdom prevail in the relevant quarters of the KP government or will Nishtar’s dream of restoring the mansion completely, and converting it into a delightful tourist attraction, remain just that — a dream.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Karachi. She also works at Hum television.