English Meltdown: Trying to Make Sense of The London Riots

“This morning I woke up in a curfew;

“This morning I woke up in a curfew;

O God, I was a prisoner, too — yeah!

Could not recognise the faces standing over me;

They were all dressed in uniforms of brutality. Eh!

How many rivers do we have to cross,

Before we can talk to the boss? Eh!

All that we got, it seems we have lost;

We must have really paid the cost.

(That’s why we gonna be)Burnin’ and a-lootin’ tonight;

(Say we gonna burn and loot)Burnin’ and a-lootin’ tonight;

(One more thing)Burnin’ all pollution tonight;

(Oh, yeah, yeah)Burnin’ all illusion tonight.”

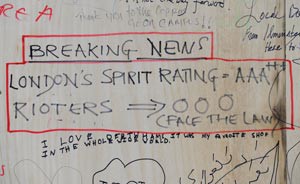

WHATEVER its original context, Bob Marley’s song could arguably have served as a soundtrack for the series of urban explosions that rocked England’s largest cities last month. Inevitably, the orgy of burning and looting has prompted a degree of soul-searching, and a variety of explanations, ranging from Prime Minister David Cameron’s charge of “sheer criminality” to the rather more optimistic conclusion that it was effectively a revolt of the underprivileged.

There is little debate, however, about what sparked the conflagration: the fatal shooting by police in London’s Tottenham area of Mark Duggan, a young father of mixed-race parentage, and the authorities’ refusal in the immediate aftermath of the killing to come clean about the incident or even to engage with the dead man’s traumatised family. The initial implication that Duggan had fired the first shot was not borne out by ballistic evidence, and a peaceful protest by his family, friends, and concerned citizens made way within hours for a riot in Tottenham.

What happened next was intensely alarming: similar riots broke out in other parts of London such as Brixton, Hackney and Croydon. Shop windows were smashed and looters helped themselves to the goods within. Buildings and vehicles were set on fire. The frenzy was unrelated to Duggan’s fate. It was only a matter of time before other English cities — Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester — were aflame. In any number of areas, anarchy prevailed for hours before the police intervened in sufficient force to make a difference.

The sequence of events and the location of the disturbances leave little room for doubt that certain pockets of urban England were effectively tinderboxes. Much has been made of largely anecdotal evidence that criminal or semi-criminal gangs coordinated their actions through social media, notably BlackBerry Messenger — leading to calls that such services ought to be shutdown.

The absurdity of demonising a tool, notably one that has attracted considerable praise for its role in facilitating the unrest that has been toppling Arab dictators, goes to the heart of a response to the riots focused on tackling the symptoms rather than examining, let alone combating, the causes. The most obvious example of this deplorably unimaginative approach lies in the harsh sentences that have been meted out to first-time offenders guilty of nothing more egregious than swiping a cheap carton of bottled water from a vandalised supermarket or a failed attempt to organise a riot via Facebook. In one of the first successful appeals against this clearly counterproductive phenomenon, a young mother in Manchester was freed after being sentenced to five months in prison simply for handling a pair of shorts looted by her housemate.

The absurdity of demonising a tool, notably one that has attracted considerable praise for its role in facilitating the unrest that has been toppling Arab dictators, goes to the heart of a response to the riots focused on tackling the symptoms rather than examining, let alone combating, the causes. The most obvious example of this deplorably unimaginative approach lies in the harsh sentences that have been meted out to first-time offenders guilty of nothing more egregious than swiping a cheap carton of bottled water from a vandalised supermarket or a failed attempt to organise a riot via Facebook. In one of the first successful appeals against this clearly counterproductive phenomenon, a young mother in Manchester was freed after being sentenced to five months in prison simply for handling a pair of shorts looted by her housemate.

It is barely a secret that prisons in Britain, as in many other parts of the world, are breeding grounds for criminality. Can it seriously be expected that those who spend a few years behind bars for helping themselves to an armful of goodies from behind a smashed storefront will emerge from jail, with a criminal record and thereby diminished prospects of employment, as model citizens?

Similarly, the Cameron government’s determination to withdraw welfare benefits from anyone charged with (and not necessarily convicted for) looting offences can only serve to exacerbate the conditions that prompted such behaviour in the first place.

Much has been made, with some justification, of the role played by a blatantly consumerist society in prompting acquisitive action. No doubt, being bombarded with messages about must-have sneakers or smartphones creates a want that for many cannot easily be satisfied. When a desirable object that was previously out of reach on account of unaffordability suddenly becomes accessible, how many of the would-be consumers are going to stop and wonder about whether they might be breaking the law?

The fetishisation of such goods, however, is only one aspect of capitalism. The key factor is the inequality it breeds. Britain has, no doubt, been a capitalist society for a couple of decades. In the aftermath of the Second World War, however, a concerted effort was made to ameliorate some of the system’s worst excesses. The National Health Service (NHS) and government-funded education were among the more notable reforms introduced by the Labour Party. They went more or less uncontested by the Conservatives — until Margaret Thatcher assumed power in 1979, equipped with a dogged determination to dismantle the welfare state.

Two years later, riots erupted in several of the blighted areas that have lately been in the news — Tottenham, Notting Hill and Brixton in London and Toxteth in Liverpool. There was a racial element to them at the time, with the victimisation by police of immigrant communities serving as one of the sparks. There was plenty of breast-beating back then too, and Thatcher came up with prescriptions remarkably similar to the ones that Cameron has lately been offering. The Scarman inquiry unearthed plenty of evidence of institutionalised racism in the nation’s police, and reforms were ostensibly put in place.

Yet it emerged last year, under a law that enables police to stop and search anyone in particular areas without an obvious cause for suspicion, that blacks are 26 times likelier to be accosted than whites. More broadly, the ratio is seven to one.

Yet it emerged last year, under a law that enables police to stop and search anyone in particular areas without an obvious cause for suspicion, that blacks are 26 times likelier to be accosted than whites. More broadly, the ratio is seven to one.

Another phenomenon that Thatcher and her successors have been more or less equally reluctant to heed is the rising levels of alienation that inevitably ensue as economic disparities deepen. Much has lately been made by Cameron and others of family breakdown and the lack of parental responsibility that enabled teenagers to embark on a riotous spree. Once again, this is an instance of confusing symptoms with causes.

Does it make much sense to expect folks to exercise moral authority when they can offer their kids little hope of a decent education or job, when some of them are barely able to put food on the table? And why should anyone be surprised when youngsters, who generally have nothing to look forward to, form gangs that sometimes prey on other citizens, and are tempted to become foot soldiers for organised crime networks?

Much to the consternation of racist outfits such as the English Defence League — whose fascist ideology attracted the approbation of the Norwegian terrorist Anders Behring Breivik — last month’s riots were a multicultural phenomenon in more ways than one. Not only did the burners and looters belong to a variety of communities, but so did the frontline defenders of various suburbs. As one sarcastic Tweeter put it: “Bloody immigrants! Coming over here, defending our boroughs and communities.”

The closest that Britain came last month to descending into racial violence was after three young men of Pakistani origin were run over and killed in Birmingham by a car containing looters of Afro-Caribbean descent. The victims had emerged from a mosque to stand guard over commercial properties in Winson Green. It was the eloquent appeals for a calm response by Tariq Jahan, the father of the youngest victim, that played a crucial role in pre-empting a violent response by hardheads in the Asian community.

Then there was Pauline Pearce, a 45-year-old, whose parents came from Barbados. She was filmed leaning on a stick in Hackney (where 44% of children live in poverty) as cars went up in flames all around her, roundly berating the arsonists and looters: “Get it real, black people, get real. Do it for a cause. If we’re fighting for a cause, let’s fight for a f***ing cause. You lot p*** me off. We’re not all gathering together and fighting for a cause, we’re running down Foot Locker and stealing shoes.”

The video clip went viral. “I was ranting for a good 15 minutes before the clip started,” she told The Guardian two weeks later. In the aftermath, she was also convinced of the need for a compassionate response: “We need to reach out. We need to understand. How do you expect people to know anything better? They’ve not known anything but struggle, not known anything but robbing Peter to pay Paul for the bills…”

Understanding doesn’t come easy to the elite that barely bat an eyelid when bankers get away with stealing billions, but are appalled and outraged when the dispossessed violate the norms of capitalist society. Tony Blair has lately decried official implications of a moral decline; he feels such comments make a bad impression overseas, but he is unlikely to acknowledge his crucial role in reinforcing the tentacles of Thatcherite neoliberalism, just as he refuses to admit any responsibility for the bloodbath in Iraq.

Although the comments from current Labour leader Ed Miliband have been more considered, there can be little doubt that had the Labour Party been in power, it would have reacted in much the same way as the Cameron regime. It must be noted, though, that the harsh sentences for opportunistic petty crimes have been criticised as counterproductive by some within the Conservative establishment, and the Liberal Democrats, who are part of the ruling coalition, have proposed alternative forms of punishment such as community service and bringing the perpetrators face to face with their victims.

However, given that lessons from the periodic paroxysms of violence — mindless or otherwise — in modern British history have largely gone unheeded, it would be far more optimistic to expect a reasoned response from the leading lights of the present dispensation, who are determined to deny that the swinging cuts in public spending announced earlier this year will exacerbate societal tensions and dysfunction. Just because last month’s unrest wasn’t for the most part politically motivated does not mean its causes weren’t deeply embedded in Britain’s political economy. The inability to recognise that those who are demonised as society’s worst enemies may also be its leading victims — that deprivation often has more to do with antisocial behaviour than depravation — makes it inevitable that the troubles will reignite at some point. The establishment’s worst, and not particularly far-fetched fear, for the moment, is that such outbreaks could occur during next year’s London Olympics. As Martin Luther King once noted, “A riot is the language of the unheard.”

However, given that lessons from the periodic paroxysms of violence — mindless or otherwise — in modern British history have largely gone unheeded, it would be far more optimistic to expect a reasoned response from the leading lights of the present dispensation, who are determined to deny that the swinging cuts in public spending announced earlier this year will exacerbate societal tensions and dysfunction. Just because last month’s unrest wasn’t for the most part politically motivated does not mean its causes weren’t deeply embedded in Britain’s political economy. The inability to recognise that those who are demonised as society’s worst enemies may also be its leading victims — that deprivation often has more to do with antisocial behaviour than depravation — makes it inevitable that the troubles will reignite at some point. The establishment’s worst, and not particularly far-fetched fear, for the moment, is that such outbreaks could occur during next year’s London Olympics. As Martin Luther King once noted, “A riot is the language of the unheard.”

A popular posting in the social media last month, derived from an African proverb, is perhaps equally worth heeding: “If the young are not initiated into the village, they will burn it down just to feel its warmth.”

This article was originally published in the September 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “English Meltdown.”

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.