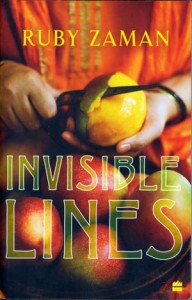

Book Review: Invisible Lines

By Leena | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 14 years ago

is the first novel by Ruby Zaman, a Bengali writer who is also a lawyer and social worker. The highly personal story revolves around a character of Bihari-Sylheti origin and, through her, examines how the creation of Bangladesh divided the country’s own people.

is the first novel by Ruby Zaman, a Bengali writer who is also a lawyer and social worker. The highly personal story revolves around a character of Bihari-Sylheti origin and, through her, examines how the creation of Bangladesh divided the country’s own people.

While much of the story is set around 1984 in London, where Zeb the protagonist is settled, there are pivotal flashbacks to the separation of East Pakistan in 1971 and the trauma suffered by its population. This is significant because few notable exceptions notwithstanding, the representation of individual experiences during independence are missing from South Asian literature. This reason alone should make Invisible Lines — a searing depiction of the price one has to pay for freedom — worth a read.

Zaman begins her tale on a dreary winter day in London, where the protagonist Zeb is entering the Bangladeshi Embassy. The story gradually unfolds and a few brief chapters take the reader back to Chittagong where we see how events in the run-up to the war catch Zeb and her opulent surroundings wholly unawares. Ultimately, Invisible Lines is about a journey through the tangled web of war and human relationships. Zaman does not simply focus on Zeb’s journey but keeps the reader engaged. Through Zeb, we encounter a number of characters including Shafiq, the brave Muktijodda whom she falls in love with but who eventually marries a “Punjabi maiden,” and Didi, the elderly woman responsible for running Zeb’s household and a silent witness to the brutality of life. In addition, the omniscient narrator guides the reader through late 1960s’ nightlife in instances mentioned in the following extract: “Zarina begum’s aggressive wooing of socialites expanded to include the elite of Chittagong society. The deputy commissioner’s wife was often asked over for a cup of tea and a game of Mahjong. The district judge’s wife, the young, fashionable wives of army, navy and railway officers stationed at Chittagong, the families of local MPs and the chief medical officer’s wife were often invited to a ladies’ lunch or high tea.”

Though this entire situation makes for potentially fascinating content, Zaman’s writing style is unfortunately more akin to newspaper reportage. She presents key characters in a direct and factual manner and one almost loses track of who is related to whom and in what way. In addition, despite placing her characters in traumatic situations, Zaman fails to flesh them out. The dialogue is stilted and critical plot points such as Zeb’s relationship with her mother are not given proper closure.

The novel is, in the end, redeemed by Zaman’s honesty and her first-hand experience with that period in history. Invisible Lines features characters that all Bangladeshis can identify with, particularly in the depiction of the struggle of citizens divided between their patriotism towards Pakistan and their desire for independence. What Zaman’s prose lacks in lyrical beauty is more than made up for with the emotion she invests in her story.

This book review was originally published in the September 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Fractured Reality.”