Anna Hazare: India’s New Superhero

By Sujoy Dhar | News & Politics | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 14 years ago

The Man who Re-ignited the Gandhian Way

The Man who Re-ignited the Gandhian Way

Like almost every Indian, I have grown up on a staple diet of Bollywood movies. More than the special effects and feats of Hollywood’s Batman or Superman, I found greater stimulus in the high-octane, emotion-dripping dialogues of our traditionally righteous, larger-than-life Bollywood heroes. I loved their indignant ideas on social justice and a cocktail of violent and non-violent means to achieve them.

Times have changed, but the Bollywood hero’s rebellious streak and angry man image remains the same. I think there must be a socio-cultural reason behind their evolution. When they were given form and shape on Indian celluloid, the nation was young and freedom-struggle architects like Mahatma Gandhi and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose were still a strong influence on the creative world.

In the 1970s these heroes were fighting smugglers, dacoits, drug dealers, illegal businessmen and invisible gang leaders in their hideouts on some private island. By the 1980s, politicians became the favourite punching bag of Bollywood films. Politicians were bashed along with murderers, rowdies, rapists, rioters and corrupt practitioners. In recent times Bollywood underwent a transformation to include sensible content and rational and realistic heroes, sets and locales, however the stereotypical politician remains the same. They remain a scheming, devious and corrupt lot, only sobered outwardly because in an age of electronic media all their moves are tracked. So come 2011, our Bollywood hero continues to battle politicians with everything from guns, sting operations, brain, brawn, and even “Gandhi-giri.”

But after years of watching and rooting for Bollywood’s imagined “wronged common man turned superman,” Indians this year discovered a real-life hero.

Their new hero does not romance a gorgeous heroine, he is not all of six feet tall, and he is not a sinewy stud with a gym-crafted torso. Instead in the twilight of his life at 74, when he is not fasting, he lives in a temple. He is a veteran soldier who fought the 1965 India-Pakistan war and was the lone survivor in air attacks in which all his comrades died. The cruelty of war was a turning point in his life. He never mongered war since it is fought with guns. He is a simple, artless Indian, oozing bygone charm, often sporting a pointed white Gandhi cap now a national rage, and one who brags about his bachelorhood as a sacrifice, referring to a time when abstinence and celibacy were considered a huge virtue, before a modern-day crowd of thousands and TV viewers in millions.

He carries a weapon. The weapon is his “fast” and though it is not produced in any arms factory, it beats down fast and furious on politicians who discovered its potency the hard way. It sucks into its vortex big-time politicians with big-ticket corruption records. Even the prime minister of a nation of nearly a billion-and-a-half people, bows down before his moral force, in a country where 64 years after independence not a file moves in government offices without a bribe, kowtowing, or political influence. Meet Anna Hazare, the most credible face of a growing anti-corruption uprising focused currently on getting a strong Lokpal (ombudsman) Bill (which will form an anti-corruption agency with sweeping powers) passed through parliament.

The world’s largest democracy is surrounded by neighbours who suffer military regimes that overthrew democratic governments, but the lone achievement of upholding parliamentary democracy cannot be a validation for no-holds-barred corruption and crony capitalism. But as recent events turned out, democracy has not failed India. While many argue that Anna Hazare’s brinkmanship degenerates his movement into an uprising against parliament’s supremacy to enact laws and run the nation, it is only the politicians who are to be blamed for the situation where people even suspect that their donations given to disaster funds named after the prime minister and chief ministers, may not reach the victims.

When my readers in Pakistan read this column, Anna Hazare may not be fasting and perhaps some breakthrough may have been achieved. He may have been taken for a ride by a powerful state, pressed for a bargain between the Anna Hazare group and the Manmohan Singh government. In the meantime, streets, rally grounds and social media forums, teeming with people and their voices excite me immensely and offer hope for India.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has vowed to fight corruption at every forum since large-scale scams were unearthed in the past one year. But his weakness in governance has failed to produce an effective mechanism to fight the menace. Under media pressure, ministers and lawmakers were sent to jail and courts refused them bail, but Anna Hazare’s indefinite hunger strike protest to form an effective ombudsman or anti-corruption agency (Jan Lokpal) turned into a nationwide movement, with thousands and thousands of people pouring out into the streets in his support.

Surrounded by advisers who are eloquent legal eagles, Manmohan Singh clearly bungled when ahead of his protest fast, Anna Hazare was arrested and taken to the same Tihar Jail in Delhi where the biggest scam artists are now languishing. By the evening of August 16, with people heading to Tihar jail in throngs, the government developed cold feet. They had no other option but to release Hazare and allow him to sit out his fast at a public venue, the Ramlila Maidan in New Delhi.

Hazare had threatened to fast after the government tried to overrule the draft of the Lokpal Bill formulated by five civil society members of the drafting committee, which the government formed after Anna’s first round of fasting in April, and which also included five government ministers.

The draft of the Bill formulated by Anna’s civil society members demanded that the prime minister, higher judiciary and lower bureaucracy also come under the purview of the proposed anti-corruption agency. The government in turn, came up with its own draft dubbed as the “Joke-pal Bill” by civil society. They were so blinded by their own self-importance, that they did not foresee that people in the thousands would take to the streets without any organised cadre-based political set-up.

As people across Indian cities and towns and villages rallied in support of Hazare, it was a warning not just for the Congress party, but to the entire political class that India’s civil society was revolting in the true Gandhian way. The peaceful nature of this mass movement has, in fact, stunned all.

I have mentioned in my previous columns the astronomical figures of each financial scam. According to the estimates of the government’s Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), a single financial scam involving the issuance of second generation telecom licenses cost the exchequer about 39 billion dollars. Last year, a report released by Washington-based Global Financial Integrity said India could be losing at least 19.3 billion dollars annually in illegal flows out of the country

The opposition BJP, which was also embarrassed by its own scam-tainted government in the southern state of Karnataka, appeared cleaner than the completely tainted Congress or its alliance partners; but that is no consolation to people disgusted with graft and rising prices.

As political parties lost the plot, civil society stepped in. Anna Hazare, who till recently was a Gandhian leader known to protest and fast, and was limited to the western state of Maharashtra, soon became the face of middle-class anger against the system.

Anna Hazare articulated what India’s “aam admi” (common man) wanted to tell its leaders. The anti-corruption agency that the Anna Hazare group wants to push down the government’s throat became a symbol of the people’s popular anger telling politicians that they cannot always have their way in the name of parliamentary democracy.

Fortunately, a section of the politicians in India are at least trying to take up the issue. I spoke to Kalikesh Singh Deo, one of India’s younger lawmakers representing the regional Biju Janata Dal party that rules the eastern state of Orissa. “Perhaps this uprising will bring better democracy,” he said to me.

Postscript: Amid celebratory cries of victory at the Ramlila Maidan in New Delhi, Anna Hazare broke his fast on the 13th day of his protest on August 28, 2011, after the Indian parliament and the ruling government bowed down before his demand for a strong anti-corrruption agency.

Farewell to the Candyfloss King

Farewell to the Candyfloss King

India’s rock ‘n’ roll hero of the ’60s bids adieu.

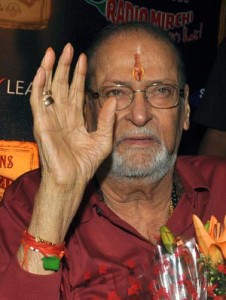

August was a sad month for the Indian film industry. Shammi Kapoor, often referred to as the Indian Elvis Presley for his frenetic dancing jigs, passed away on August 16. Born as Shamsher Raj Kapoor on October 21, 1931, Shammi was one of India’s greatest entertainers on celluloid. He was the king of rock ‘n’ roll in the films of the 1960s, an era when Bollywood movies attained a new height of glitz and glamour with lavish sets, fashionable costumes and exotic locales.

But it was not frenetic dancing alone that made Shammi Kapoor so popular. It was the overall candyfloss flavour and stylised mounting of his films, and the powerhouse package of dance, locales and romantic escapades that made him a timeless phenomenon.

In the past decade, candyfloss became a rage in Bollywood once again, but the entertainment value of the old Shammi Kapoor films could not be matched by these new filmmakers, despite their technical wizardry.

Who can forget the impassioned “Ya-hoooo” cries in Junglee, opposite the beautiful Saira Banu, or Shammi’s dandy globetrotting appearance in An Evening in Paris opposite a bikini-clad Sharmila Tagore. He also took us on a roller coaster ride in Teesri Manzil, Indian cinema’s all-time favourite musical thriller.

Shammi Kapoor was the second son of film and theatre legend Prithviraj Kapoor, sandwiched between the eldest, Raj Kapoor, and the youngest Shashi Kapoor.

Born in Mumbai, Shammi was raised in Kolkata in the heyday of New Theatres Studios, to which Prithviraj Kapoor was closely associated. After spending his early childhood in Kolkata, Shammi went to St Joseph’s Convent (Wadala), Don Bosco School, and later to the New Era School in Mumbai.

Shammi made his first appearance in the movie Jeevan Jyoti in 1953, directed by Mahesh Kaul, starring Shashikala and Leela Mishra. He went on to act in more than 100 films, many of which were roaring hits for their song and dance numbers. When Hindi cinema switched over to colour, he was the leading star in films with lavish sets and picturesque locales in Kashmir and abroad.

In a recent interview Shammi said: “The most wonderful thing about the films of my times was innocence. Those were happy movies…hero meets heroine, chases her, sings seven to eight songs to impress her, then last mein Pranji ki tarah ek villain bhi aa jayenge… I belong to the era when films were simple, they didn’t tax your brains; at least, my films were not thought-provoking, they were pure entertainment.”

While we will miss Shammi Kapoor, the innocence of a cinema of a different era will live on.