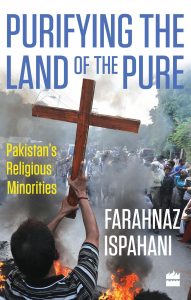

Book Review: Purifying the Land of the Pure

By Hurmat Ali Shah | Bookmark | Published 9 years ago

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah stood before the Constituent Assembly on 11 August 1947, he had no idea that his words as to the future of political identities informed by religion in the new state of Pakistan would come true, albeit in reverse. Hindus have ceased to be, and Muslims have also ceased to be, except the Sunnis. Jinnah in his envisioning of Pakistan as a non-ideological state, appointed Jogendar Nath Mandal, a Hindu, as law minister and Sir Zafarullah Khan, an Ahmadi, as foreign minister.

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah stood before the Constituent Assembly on 11 August 1947, he had no idea that his words as to the future of political identities informed by religion in the new state of Pakistan would come true, albeit in reverse. Hindus have ceased to be, and Muslims have also ceased to be, except the Sunnis. Jinnah in his envisioning of Pakistan as a non-ideological state, appointed Jogendar Nath Mandal, a Hindu, as law minister and Sir Zafarullah Khan, an Ahmadi, as foreign minister.

However, efforts to put Pakistan on the road to being an ideological state had already started in Jinnah’s lifetime. Malik Ghulam Muhammad and Chaudhry Muhammad Ali, in pursuit of their obscurantist agenda, tried to muddy Jinnah’s clear vision for the state by orchestrating the suppression of the founding father’s outstanding August 11 speech. In that speech the founding father stated that he had envisaged the country as one that guaranteed equal status and protection to all, regardless of caste, creed and faith, and even went on to say, “I don’t know what a theocratic state means.” Meanwhile, Chaudhry Khaliq-uz-Zaman and Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan were dubbing Pakistan as the land of the pure.

What made Jogendar Nath Mandal — a symbol of Jinnah’s pluralistic vision for Pakistan — leave Pakistan after only three years of its existence? What made the population of Hindus in East Pakistan dwindle from 20 per cent in the 1951 census to 12 per cent in the 1961 census? And what made the minorities shrink from 23 per cent of the population on the eve of independence to a paltry three per cent now?

Scholar and former parliamentarian, Farahnaz Ispahani, in her scholarly book Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities, has explained the disastrous turn of policies regarding minorities, which answers the questions raised above. She has delineated the undercurrents and forces that were at work from the inception of the new state and which translated into actual policies to define Pakistani citizenship based on faith and excluding minorities from the polity.

Ispahani has pointed out that, in order to distract attention from their resistance to the creation of Pakistan and to carve out a space for themselves, the religious parties affiliated with the Deobandi school of thought capitalised on the rhetoric of the Muslim League in the struggle for Partition. They made the exclusion of minorities from state institutions and reducing their status in the land, their rallying cry. Official and semi-official newspapers further fanned the flames of division by declaring Hindus to be the vicious ‘other’ and labelling them traitors.

The clairvoyant call of Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy with which the book opens — “Now you are raising the cry of Pakistan being in danger for the purpose of arousing Muslim sentiments and binding them together in order to maintain you in power. This must go. Be fair not merely to your own people whom you will destroy but be fair to the minorities” — was discounted and Pakistan continued on the path of Islamisation which had been set by the Objectives Resolution of 1949. Ispahani goes on to say that in order to cement his power base, Liaquat Ali Khan tried to appease the clerics by passing the Objectives Resolution. However, this only further emboldened the clergy which presented a plan for dealing with the minorities in 1950, sanctioned by 31 clerics. This ultimately resulted in the 1953 anti-Ahmadiyya riots which claimed 2000 lives.

According to Ispahani, the state of religious intolerance reached its nadir with the Islamisation drive under Zia. The religious rhetoric, which had been challenged vociferously by the secular and progressive politicians of the 1950s, was now the official policy of the state. From inculcating young and gullible minds with prejudice towards the minorities through falsifying history, to institutionalising instruments of legal oppression, the Zia regime put the last nail in the coffin of intolerance towards the minorities.

Representational diversity can, in some cases, heal material inequality. But the minorities in Pakistan have been unfortunate that through the introduction of the system of separate electorates, any chance for them to raise their voice against injustice has been taken away. Further Islamisation by the Nawaz Sharif government, coupled with state-sponsored militancy, which targeted the minorities — both non-Muslims and other Muslim sects — resulted in horrific crimes against the minorities. Pervez Musharraf made some overt gestures of fighting sectarian militants but his avowed support of the jihadis in Kashmir and the Taliban in Afghanistan, made a farce of his half-hearted attempts at ameliorating the fate of minorities in Pakistan. Now, even with the democratic government in place, the instruments of intolerance against minorities can be challenged only on pain of death, as was the case with Salman Taseer and Shahbaz Bhatti.

One theme is constant in this sad story of state-perpetuated intolerance and institutionalised bigotry towards minorities: ‘Otherize,’ them (minorities) to reinforce the confessional identity of the state. The writer has diagnosed the futility of Islamism as, “the pursuit of religious purity is not an attainable goal. It has hindered Pakistan’s progress and rendered it insecure … Instead of allowing bigotry to cloak itself in the garb of a state religion, Pakistan would advance better as a non-confessional state.” The process of reform, according to the writer, can begin with, “dismantling the constitutional, legal and institutional mechanisms that have gradually excluded minorities from the mainstream of Pakistani life.”

The power elite must realise now that the exclusionary process of ‘otherisation’ is a consuming one and, like the monster that it is, it constantly needs tributes. It always looks for some group of people to be consumed as a whole! Pakistan has to move towards a civic identity of a nation-state based on shared citizenship from the militarist conception of a confessional and ideological state. This book, with its detailed analysis and exhaustive facts, helps in better understanding the trajectory of the confessional state and presents a well-articulated case for Pakistan to move towards a non-confessional and inclusionary state.

Hurmat Ali Shah is a freelance journalist, interested in politics, society and culture. He is pursuing his PhD in South Korea.