Art Review: Shammi Ahmed

By Nusrat Khawaja | Art Line | Published 9 years ago

Shammi Ahmed’s inclination to paint the female face is an enduring one. She displayed her latest series of portraits titled ‘Beauty is Eternal’ at Momart Gallery, which she established in 1994 and continues to run.

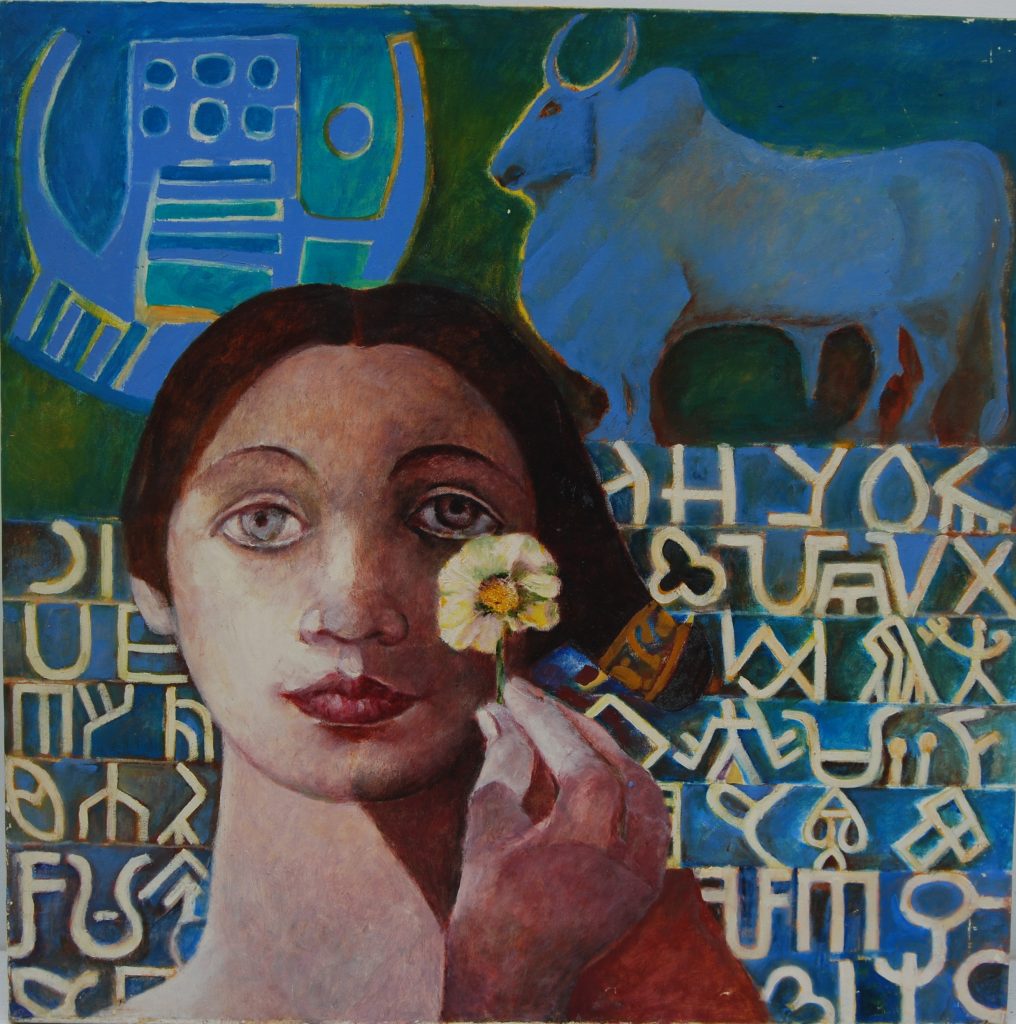

Upon entering the spacious hall of the gallery, one is momentarily transfixed by the limpid gaze of dozens of women’s faces that gaze out directly from the picture plane. These faces are larger than life-size, and this lends them a monumental quality. Each woman holds a blossoming stem or single flower which is a recurring symbol of feminine beauty in Shammi’s work.

Shammi is confidently and unapologetically old-school in her personal approach to art, which contrasts strongly with the burgeoning growth of conceptual and contemporary art in the country. She mentions Sadequain, Shakir Ali and Ahmed Pervez among some of the painters she admires. Shakir Ali’s many students included Jamil Naqsh, who happens to be Shammi’s cousin. She developed as an artist under Naqsh’s mentorship. She continues to solicit feedback from him and she mentions the importance he pays to proportionality when critiquing her paintings.

The formal quality of her portraits is communicated by the emphasis on form which clearly differentiates the figure from the background. There is a slight repression of three-dimensionality which flattens the facial outlines. The feeling of mass comes through strongly in the colour shapes that create contours. This technique gives away her artistic debt to Naqsh, who in turn was fascinated by Cezanne’s technique of building volumetric form from shape and colour.

The formal quality of her portraits is communicated by the emphasis on form which clearly differentiates the figure from the background. There is a slight repression of three-dimensionality which flattens the facial outlines. The feeling of mass comes through strongly in the colour shapes that create contours. This technique gives away her artistic debt to Naqsh, who in turn was fascinated by Cezanne’s technique of building volumetric form from shape and colour.

Shammi shares her mentor’s interest in the prototypical female face. Naqsh’s style makes use of faceted geometric planes to create texture. Shammi is more nuanced in her use of geometry. She avoids strong contrasts of light and dark and creates tonal variation by subtle gradation of colour and adjacent placement of complementary hues. She always works in oil on canvas, and by applying thin layers of paint, she creates translucency. The facial features are accurately represented but the colours are more expressionistic. Some faces are painted in shades of teal and green, turquoise and burnt orange, etc. The imaginative use of colour gives Shammi’s work a distinctly Modernist quality, reminiscent of the Fauvists’ use of non-naturalistic colour in order to express a subjective sentiment rather than realism.

In the series Beauty is Eternal, which represents two years of work, Shammi has linked the notion of the eternal with that of antiquity. She has combined the portraits of her gently gazing belles with iconography from Moenjodaro. The humped cow or zebu, the enigmatic Moenjodaro script on seals, the faience bead jewelry…all the better known aspects of archaeological discoveries from the 5,000-year-old civilisation are depicted as a backdrop to the women’s faces.

In one painting, a woman bears a wicker basket on her head filled with small clay animals that might be toys. In another image a woman with a flower-filled basket is imagined as a flower seller. The trefoil icon on the robes of the so-called ‘King-Priest’ are reimagined as a window and also scaled down in the same painting to become the woman’s bindi.

The King-Priest statue from Moenjodaro features in a couple of paintings which Shammi conceptualises as a king and queen pair. The delicate statuette of the dancing girl is also represented in two paintings, one showing her from the front and the other from the back. Shammi’s rendition of this most iconic find from the archaeological site takes artistic license by making her shape more robust than seen in the artefact.

She tells a fairy tale that supports her belief in the aesthetic principle that ‘Beauty is Eternal.’