Frenemies Forever

By Syed Talat Hussain | Cover Story | Published 12 years ago

It was a strange meeting — stranger than any other the participants had seen in the recent past. In the middle of a normal course of discussion on what prejudiced the US view of Pakistan, the US Secretary of State John Kerry threw caution to the wind and became unusually candid and harsh in accusing Pakistan’s Intelligence Agencies of harbouring the Haqqani Network militants. This was not the usual litany of complaints from Washington. Nor did the occasion demand reading the riot act to Pakistan. The leader of the US delegation, a right-hand man of President Barak Obama, was openly saying that this support to the Haqqani network was being given as a matter of state policy.

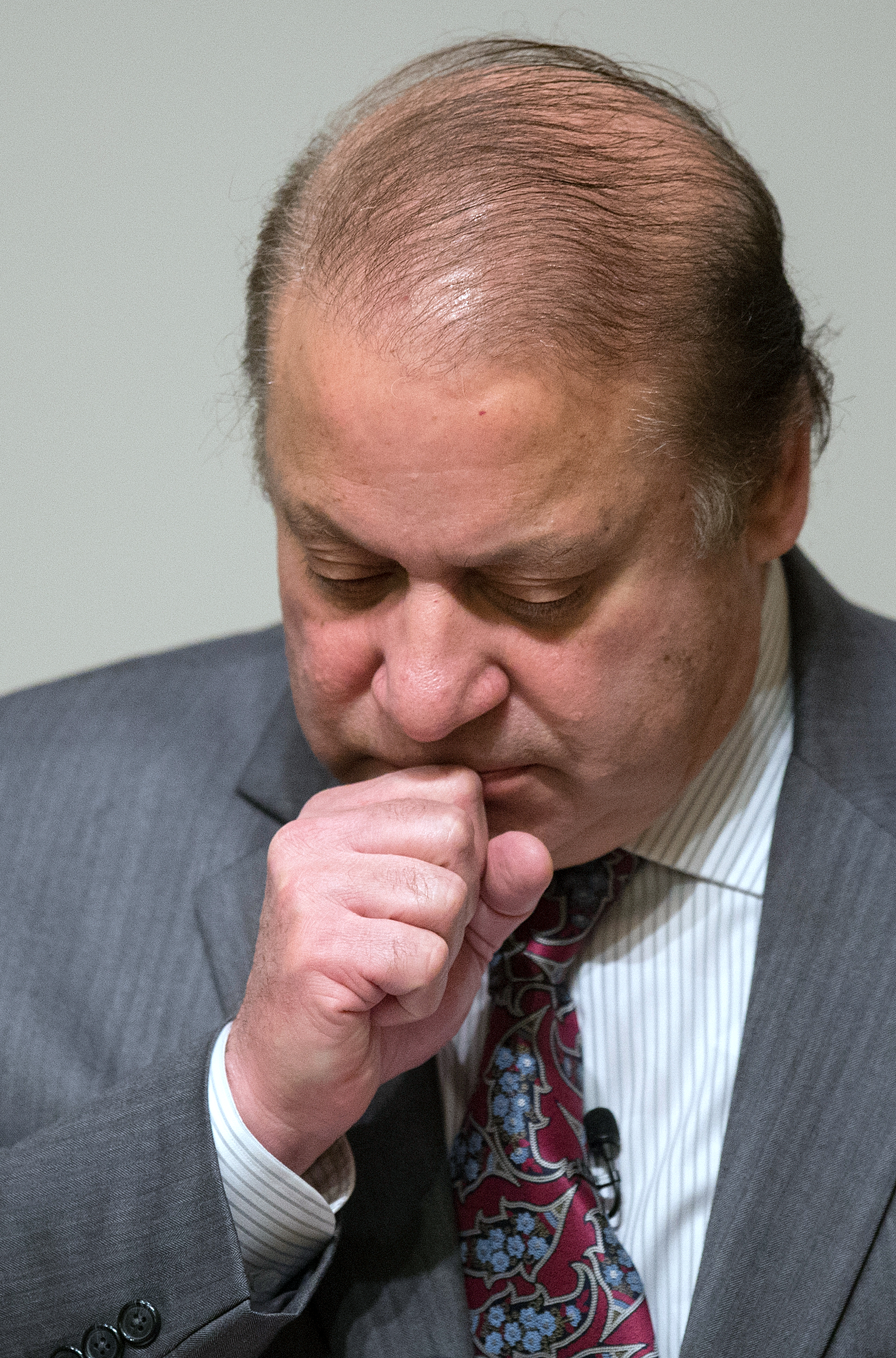

Even then, the ruthlessness of the narrative would not have been so awkward had it not been for the fact that Kerry was saying all of this in the presence of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, the Chief of Army Staff Ashfaq Pervez Kayani and the ISI Director General Zaheerul Islam.

The prime minister was stunned and but he soon recovered and made a typical Sharif-move: He deflected the charge towards General Kayani. Suddenly, instead of two there were three parties in the room: the US delegation, the top civilian leadership and representatives of Pakistan’s formidable establishment.

Sensing the explosive nature of Kerry’s attack and discomfited by the prime minister’s silent but clearly-conveyed intent of not being the advocate of Pakistan’s innocence, General Kayani responded: “Where is the evidence? This issue has been hanging fire for as along as I can remember. Every now and then it is brought up to vitiate the environment but you have never ever given us any proof to back these statements.” His tone reeked of anger. This was so also because in preparatory meetings leading to the main conclave, the US side had never indicated that this was an issue that would be brought up before the prime minister. It was a sniper hit from the dark.

Kerry asked rhetorically whether it was true that no evidence was ever brought forth to support the contention.

“Never. You can check your record. But now we have to sort it out. We cannot do this, make accusations like this. This is not on.” General Kayani was fuming.

All this while Prime Minister Sharif remained a quiet spectator. He did not want to jump in on the matter, so he let it remain a bilateral subject between John Kerry and General Kayani. The rest of the meeting was uneventful. Later in the day, the DG ISI had a detailed meeting with the prime minister and explained to him the context of what Kerry had said. It is not known whether the prime minister was convinced of the rebuttal that Washington’s charges were wholly untenable.

The evening had something even more bizarre in store. As Kerry and core members of his team were feted by General Kayani at his residence, the morning incident was not brought up by either side. Propriety and decorum were maintained and the conversation stayed within the parameters of agreed understandings. Around wind-up time, Kerry asked General Kayani if he could see him in private, without any note-takers. Kayani agreed, but did indicate to the DG ISI to join in. As per protocol, the visitor could not object to the three being a crowd. “I wanted to express my regret for what I had said in the morning. We have no proof for it.” This was surreal. The US secretary of state was going back on what he had stated officially in front of the prime minister of Pakistan. Kayani remained silent. He did note down in a little diary exactly how Kerry had phrased his U-turn. Later on, he read portions of these notes to a flabbergasted US ambassador, whose only response was shaking of the head in disbelief.

This matter of Kerry speaking out of both sides of his mouth to the civilian and military segments of Pakistan’s top hierarchy is now part of the record maintained by the foreign office and the prime minister’s secretariat. But while these notes make for astounding reading in diplomatic double-speak, these aren’t the most amusing part of the record. A two-and-a half page document takes the cake in the curious ways Washington’s engagement with Pakistan is panning out these days.

This particular text is a more recent addition. This was handed over to Pakistan by James Dobbins, US Special Representative on Pakistan and Afghanistan, just before Prime Minister Sharif embarked on his all-important official visit to the US last month. The two-and-half-pager puts in black and white the accusations Kerry had made in the earlier meeting. The document quotes incidents of Pakistan’s support to the Haqqani Network but leaves the final findings to be done by Pakistan through its own investigations.

Clearly, Kerry’s admission of mistake at Kayani’s residence was a courteous deviation from the main script that the US administration has created for dealing with Pakistan. Beyond hollow apologies and make-overs, the real message is simple: Islamabad is the problem, and within Islamabad, the big building in Aabpara housing the ISI is the root concern. Until the affairs within this building are sorted out, Pak-US ties would remain trouble-prone.

It is either a compliment to the dexterity of US diplomacy or a statement of Pakistan’s vulnerability that even while a fire of distrust burns between Washington and Pakistan’s top-brass, regular engagement still remains unaffected.

Sharif’s refusal to appoint a full-time foreign minister, a defence minister and even a law minister is indicative of his intent to be personally in control of vital matters of national security. This fulfills his other personal ambition: to reverse the ingress and hold of the army on national security matters and eventually create an environment like in Turkey under Tayyip Erdogan, where habitual coup-makers are cornered forever.

Sharif’s refusal to appoint a full-time foreign minister, a defence minister and even a law minister is indicative of his intent to be personally in control of vital matters of national security. This fulfills his other personal ambition: to reverse the ingress and hold of the army on national security matters and eventually create an environment like in Turkey under Tayyip Erdogan, where habitual coup-makers are cornered forever.

Kerry is just a call away for the GHQ and the other way round. Both sides continue to show deliberate intent to somehow manage these thorny issues. Sometimes they do succeed as well. That was partly why the Dobbins paper did not become the point of discussion or contention when Prime Minister Sharif sat down in his official parleys in Washington. Emissaries from GHQ had gotten the message across to Kerry’s office that there would be much rancour and ill-will if the prime minister was embarrassed on this count. Both sides agreed that this matter should be resolved separately by intelligence and military representatives, who would sit face to face across the table, and sift fact from fiction on the basis of evidence.

It does not require super analytical abilities to figure the matrix Washington is using to conduct its relationship with Pakistan at the moment. It is greasing the wheels of friendship with the civilian government, in the hope that this will enable Mr Sharif to take full charge of foreign and defence affairs, and curtail the role and influence of the army in decision-making.

So far there is convincing evidence that Mr Sharif is comfortable in playing this role. “Being in charge” is his favourite political ringtone. And he is playing it loudly. His refusal to appoint a full-time foreign minister, a defence minister, and even a law minister is indicative of his intent to be personally in control of vital matters of national security. This fulfills his other personal ambition as well: to reverse the ingress and hold of the army on national security matters and eventually create an environment like in Turkey under Tayyip Erdogan, where habitual coup-makers are cornered forever.

That, in part, explains why he has not stuck his neck out for the army, whenever it has come under a barrage of criticism or accusations, not just from Washington but from Kabul and Delhi as well. On several occasions, the army had to ask (and in certain cases even draft) an official response to the charges coming from outside. On other matters, such as giving a red-carpet treatment to the slippery Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, or persisting with peace offers to Delhi even in the face of stern rebuffs, Prime Minister Sharif has practically turned a deaf ear to assessments coming from the GHQ. Recommending known army critic Kamran Shafi for the post of High Commissioner in UK is another way the prime minister has chosen to signal his intent.

Of course Washington, and to a lesser degree London, sense an opportunity in Pakistan to push their agenda through the newly-elected government, which is desperate for financial aid. If Prime Minister Sharif’s thinking on a range of critical issues, is in tune with their interests, they won’t mind backing him to the hilt. But in case he falters, they will stay engaged with the army in the hide-and-seek, truth-or-dare fashion they always have — and always will. Pak-US ties, at this point in time, are much more than a few agenda items on the usual discussion roster. These ties are woven into the texture of civil-military relations in the country.

The writer is former executive editor of The News and a senior journalist with Geo TV hosting a prime time current affairs program.