Constant City, Changing Face

By Naima Rashid | Art Line | Published 12 years ago

The Makkah of today is both timeless and time-bound. As a symbol in the minds of so many, it embodies ideals that defy time. As a city, it is mutable and undergoing a long-drawn overhaul. Very soon, the cosmetic surgery would be complete, and the apparatus of construction tucked away. The world will only see the finished face of Makkah.

As Makkah undergoes a facelift, some Saudi artists react to the change they see around them on canvas, trying to process the strange and the unfamiliar. In Shadia Alem’s series, the Supreme Kaa’ba of God, Makkah looks like a ghost town with its intestines slit open, infested with an army of construction cranes. A raven perches on a crane shoulder like a watchful and brooding presence; also visible are machine limbs, numbers and feathered sentinels reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe’s writing — hardly the image the mind conjures at the mention of Makkah. More like an abandoned desert town from an old western, one would say.

We often feel this sense of menace and desolation when we see alien bodies in Makkah (like a McDonald’s, or the Makkah Clock Tower with its unmistakable resemblance to Big Ben). Makkah is a city we cannot see with the naked eye. We see it through the film of a narrative that plays in our minds and informs our perception; a cumulative narrative built out of the social and material culture that we, in Pakistan, have seen grow around the journey to and from Makkah — the norms of welcoming relatives who return from Umrah and Hajj, and the expectation of the token booty from them upon return: dates, white plastic bottles with zamzam, rosaries, prayer rugs and kitsch replicas of the two holy places. This narrative of reverence that builds in the mind of the non-resident Muslim acquires the status of a myth — a myth that becomes dissociated with the realities of the city, so that when we encounter images of banality and ordinariness, we rile because our familiar frame of reference for Makkah is shaken.

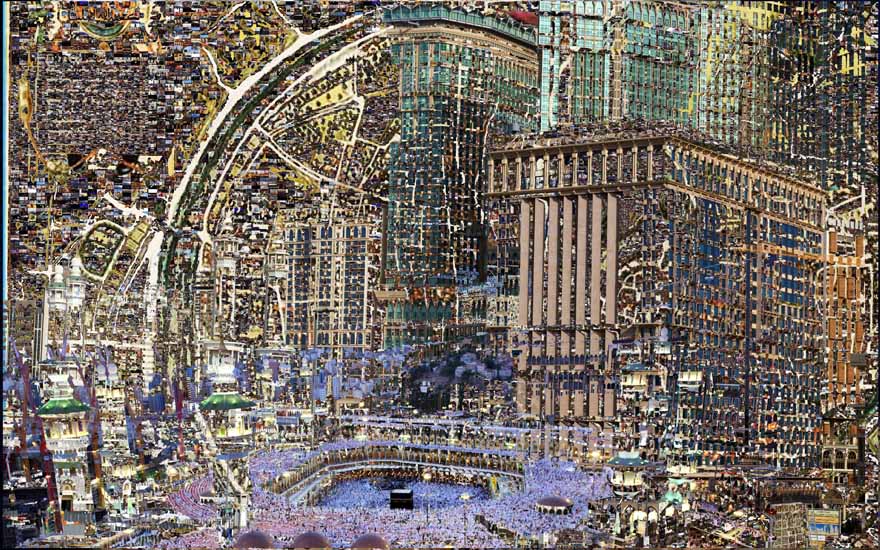

The Saudis, on the other hand, are tuned in to the realities of the city. For them, Makkah isn’t an extraneous symbol that they must journey to, but a part of their ethos, their existential denominator. ‘Makkah Street Sign,’ a stencil graffiti by a petite Hejazi artist, shows Makkah’s cityscape as a conglomerate of high rises clustered behind the Kaa’ba. One has to struggle to spot the Kaa’ba and from afar, it looks like a Manhattan skyline. A freaky and futuristic fast-forward to what Makkah will look like to our children, it also poses a question about the cultural suitability of some of the implants that Makkah has been receiving. The architectural and aesthetic inspirations for the Makkah Clock Tower are a confused hybrid of a throwback to European aesthetics, a gargantuan American scale and tasteless Middle Eastern opulence. Driving into Makkah today, our children often exclaim at the obvious resemblance to the cityscape of New York. A lot of them haven’t been to New York, but Makkah’s silhouette today resembles their visual stereotype of the American metropolis.

Not everything can be blamed on concrete, though. Sometimes, the silent hand of time can deal a blow just as harsh. How many stories of loss and survival groan beneath Makkah’s mortar? Nasser Al-Salem is a young Meccan calligrapher who comes from a family of former tent-makers for pilgrims. Ten years ago, the once-lucrative family business came to a standstill when plastic tents replaced canvas ones. His work, ‘City Nomads,’ is a chilling ode to loss. The hoarse canvas flaps, originally doors to the tents his family once made, are so spectacularly strange and useless they might as well be a relic from a Red-Indian tribe. Each one bears a number in Arabic, allotted by the government, which marks the bureaucratic stage at which each respective tent-house was, in a phased process of removal. Once human presence is reduced to numbers, it becomes easier for the conscience to handle, but every once in a while, a spine-chilling reminder like Nasser’s story will bolt up like a skeleton with a spring, and one is forced to re-imagine the story in reverse, backtracking from the objects to the numbers and finally to the chronicles of the human spirit.

Ballsy and poetic, a work called ‘The Road to Makkah’ by Abdulnasser Gharem poses a question which is well worth its weight in letters. Literally. It is a ‘stamp painting,’ in which an initial canvas is built by covering a sheet of plywood completely with dismembered letters of stamps. Stamps, in Saudi Arabia as elsewhere, are a symbol of tiresome bureaucracy and by taking them apart and rearranging the letters with subliminal echoes of critique or idealism embedded within the layer, the artist creates a first platform of subversion. Any message that is added on top, often a provocative question that tickles the mind, is read against this initial charge. Several kilometers before the entry into Makkah, a sign bifurcates the incoming traffic on the basis of faith, signalling a movement forward for Muslims, and a deflection sideways for non-Muslims. The artist recreates this sign board, begging the obvious question. Why can’t non-Muslims enter Makkah, and how does Makkah, the city and the symbol, bear the weight of the question? As a symbol, Makkah belongs to every Muslim, or perhaps any man seeking guidance. No more than the notion of God, the notion of Makkah cannot be contained in space or possessed by one man. And yet, as a city, it belongs only to Saudi Arabia. Its custodianship, the privileges and the responsibilities that come with it are the prerogative of one state alone.

Several kilometers before the entry into Makkah, a sign bifurcates the incoming traffic on the basis of faith, signalling a movement forward for Muslims, and a deflection sideways for non-Muslims. The artist recreates this sign board, begging the obvious question. Why can’t non-Muslims enter Makkah, and how does Makkah, the city and the symbol, bear the weight of the question?

Makkah will always embody this duality, the parallel but contradictory dynamics of city and symbol, of place and notion. It is at once Makkah with a capital ‘m’, a city in space and time, and mecca with a small ‘m’: a ‘mecca’, an idea of a source to which all men and seekers always have and always shall turn their heads, unbounded by space and time.