Book Review: The Last Sunset

By Nyla Daud | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 15 years ago

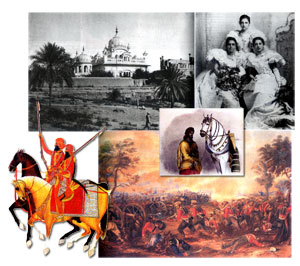

Ranjit Singh, the iconic Lion of Lahore, is no stranger to these parts. Though illiterate and only capable of putting his name down on a piece of paper, recorded fact and fictional literature acknowledge him as a man with a brilliant mind for governance, military strategy and social skills, albeit a man who was also manipulative and, at times crooked. Nevertheless, he stands out as the lone Indian ruler who, for 40 years of his reign, withstood western claims about the sun never setting on the British Empire. The Lahore durbar of Ranjit Singh was a citadel of resistance against the East India Company’s imperialistic designs.

While there has been no dearth of historians, military analysts and even creative writers who have paid homage to the man who, even after 168 years of his death, continues to be written, spoken and conjectured about, Amarinder Singh, is the latest entrant in the field. In less than 300 pages, Amarinder Singh, former Indian army officer, later chief minister of Indian Punjab, and currently representing the Congress party in the Indian parliament, neatly packages the greatness, the glory, the calculative intellect and shrewd military tactics of Ranjit Singh in the face of British imperialistic design. Singh has in equal measure presented the pathos of the designed or natural results of failing political power, the palace intrigues and downright lechery that resulted in ending Ranjit Singh’s dynasty. The Last Sunset: The Rise and Fall of the Lahore Durbaris, however, a human story first and foremost, and therein lies its readability.

Where autobiographers tend to either have their faces too close to the window pane in search of the real perspective, or are burdened by personal prejudice, and where historians present such subjects in a dry-as-dust narrative making people shy away, Amarinder Singh’s book packages the protagonist as a human being, warts and all — his glorious reputation as a dreaded and respected warlord notwithstanding. Ironically sharing a common surname, both projector and projected emerge with singular identities. While Singh junior, by virtue of the lengths he has gone to research historical fact, remains mostly free of nepotistic design to glorify an ethnic ancestor, Singh senior’s esteem is upheld despite the author’s unabashed acknowledgement of Ranjit Singh’s debauchery, drinking orgies and lowly acquisitive inclination towards whatever tickled his imagination, be it the diamond Kohinoor or the beautiful Persian horse Lali. Seldom do the chinks in the writer’s armour show, when, in moments of creative weakness he lets escape a shadow or two of sympathy with his clansman. However the empathy, which has been consciously kept at bay, is fairly balanced by the hard work that has gone into researching the real story of the life and times of Ranjit Singh. It is a pity then that Amarinder Singh, in spite of his research, could not lay his hands on the third volume of the collection of daily chronicles written by Sohan Lal Suri, the vakil of the Lahore camp during Ranjit Singh’s reign and subsequent administrations. Apparently this volume, which could have provided vital information about tactical handling of the army and would have added to the book’s importance as a military document, was borrowed by a certain English Lieutenant Herbert Edwardes and never returned. What was in that volume, which the British wanted to keep under wraps, and where it is today, remains a mystery,

However, in spite of this information glitch, The Last Sunset is no mere stylistic piece of storytelling. It gives an overview of the birth, the rise and final, pathetic ending of the dynasty that remained a one-man show, with Ranjit Singh as the outstanding player, and successfully balances the strategic performance of the British camp in this great game. The parallel evolution of the Sikh army under Ranjit Singh, from an unruly fighting force, essentially based on the feudal concept, to its pruning along the lines of the French army competes with regional developments of the time, in painting the kingdom and ruler as formidable forces. The book has been written in engaging, easy-to-read language, in spite of the accompanying mathematical precision of researched material that gives it its authenticity. It moves on to how the Lahore Durbar, that once glorious citadel of Sikh zenith, began the downward spiral to become history within just six years of its founder’s passing away.

However, in spite of this information glitch, The Last Sunset is no mere stylistic piece of storytelling. It gives an overview of the birth, the rise and final, pathetic ending of the dynasty that remained a one-man show, with Ranjit Singh as the outstanding player, and successfully balances the strategic performance of the British camp in this great game. The parallel evolution of the Sikh army under Ranjit Singh, from an unruly fighting force, essentially based on the feudal concept, to its pruning along the lines of the French army competes with regional developments of the time, in painting the kingdom and ruler as formidable forces. The book has been written in engaging, easy-to-read language, in spite of the accompanying mathematical precision of researched material that gives it its authenticity. It moves on to how the Lahore Durbar, that once glorious citadel of Sikh zenith, began the downward spiral to become history within just six years of its founder’s passing away.

Amarinder Singh’s detailed delineation of the two Sikh wars and their decisive results on an already crumbling kingdom, the account of easily winnable battles lost and the exposition of the intrigues, finally comes home to roost in a depressing landscape, with a fallen Khalsa and the annexation of the state to the Crown of England with Maharaja Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, being deported to Britain. The story of the 10 years following Ranjit Singh’s death are truly tragic, for the writer manages to convey, in no uncertain terms, the underlying treachery on part of the Lahore Durbar and Sikh generals as well as the gallantry and determination of the Khalsa soldiers. It is in the two chapters devoted to the Sikh wars that intrepid readers of military strategy will be able to cast aside the romantic aura of the tale and get first-hand knowledge of the battle grounds, the formation of the forces, the commanders, the arsenal and other tools of combat. Locations and terrains are described succinctly with support from archival material in search of which, the author has apparently striven, as if it were a labour of love — or better still, a debt of honor, nay, even an exoneration of any stigma — placed at the feet of the Sikhs. The inclusion of tables, maps and drawings detailing the positioning of the warring forces on the various fields of battle is praiseworthy. Direct quotes from the journals of officers, both on and off the field, as well as the letters and excerpts from dossiers and exchanges between the parties are an added asset to the reading.

Laudable is the fact that writer Amarinder Singh’s account in no way dismisses the heroics of the British. But such acknowledgements boldly balance opinionated statements that openly portray Dalhousie as being guilty of fraud in order to feed his passion of empire building. However, for all who may doubt any bias of racial prejudice, there are annexures placed at the end of the book. These are fate and destiny sealing copies of authenticated, dated treaties, agreements, notifications and a final proclamation by the Resident at Lahore.

Thus while the tactical importance of the book as a resource of military strategy in the days when soldiers often fought hand to hand against a landscape of roaring rudimentary artillery is a reality, the romanticists amongst us will end their reading duly affected by the last lines of Amarinder Singh’s book: “Was it coincidence that none of Duleep Singh’s children (the Sikh Maharaja of the time and son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, deported to England) had any children of their own, resulting in the lineage fading out of history, or was it the hokum of Siri Guru Gobind Singhji, the tenth Guru, who had said that if anyone built a memorial to him, his dynasty and his family would end?”

Yes, Ranjit Singh did build such a memorial and of that phenomenal one-man show there remains no descendant. And therein lies the pathos of the legacy that could have been.

This book review was originally published under the title “The King and I.”