Book Review: Images of Afghanistan

By Ella Hussain | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 15 years ago

When one hears of Afghanistan, it is usually in conjunction with the words “terror” or “Taliban.” The media speaks about the region in a mechanical, cold way to the effect that the world thinks of only the many troubles afflicting the region as opposed to the individuals living within it. Images of Afghanistan is an exercise in humanising the country and reminding readers everywhere that under the multilayered social and political turmoil lies a rich, potent culture. The editors, Arley Loewen (a scholar in Persian literature) and Josette McMichael (a family medicine physician), are expatriates working and living in Afghanistan who realised the beauty of Afghan and Persian culture over their many years spent working with the Afghan people. The compilation of this work was an attempt to remind those watching Afghanistan, as well as those living within it, that there is more to the country than the war and violence that continues to make headlines across the world.

The book looks broadly at two aspects of Afghan/Persian culture: art and literature. Under the heading of Art, the editors have discussed calligraphy, paintings, handicrafts, music and cinema. Literature informs the readers of the ancient Persian tradition of poetry and storytelling, recounting the Sufi poet masterminds and their works, as well as discussing new literature coming out of the region. Loewen and McMichael point out that the study of the art and literature of Afghanistan becomes a study in anthropology; novels, stories, poetry, music and traditional crafts — all become windows into a rich culture the world knows little of, till now. Images of Afghanistan aims to fill this vacuum by creating an entry point into the interesting Afghan tradition, so that other writers and researchers will realise the potential of this subject and follow suit.

The book has been divided into seven sections. The first is an introduction into Afghan history and a discussion on the importance of recounting cultural and traditional aspects of Afghanistan. In this section the editors recount the various rulers of the region — from local amirs to Mughal rulers, and then the British. The Afghani experience involves the cultures of a varied range of ruling hands. As a result, the local traditions and norms are a unique blend of subcontinental experiences. This explains the flavour and depth of Afghan culture. In addition to being an interesting read in general, the editors have offered a well-rounded synopsis of the Afghan timeline, which serves as a good introductory point to those looking to learn more specifically about the nation’s roots.

After introducing the reader to the geo-political origins of Afghanistan, the book proceeds to tackle the components of its culture. An integral element of this culture is the literary work that has come out of the region.

Part two is concerned with Dari literature or Afghan-Persian literature, whilst part three is about Pashto literature. These sections shed light on the thousands of years of poetry running subterranean to mainstream culture. Part four illustrates this ancient tradition; it is labelled “Themes of Culture” and contains the poetic genius of great minds from Hafiz to Maulana Rumi and beyond. The importance of religion to the average Afghan is easier to understand when keeping in mind the fact that the cultural milieu in which he/she has been raised is centred around religion and spirituality. The medieval works of poets like Hafiz, with their emphasis on mysticism and the desire to be re-united with God, are well known amongst the Afghan people. Poetry permeates every Afghani class and is not circumscribed to the educated elite, as is often the case in western cultures. The function of poetry in Afghani life is as pertinent today as it ever was in the past.

Part two is concerned with Dari literature or Afghan-Persian literature, whilst part three is about Pashto literature. These sections shed light on the thousands of years of poetry running subterranean to mainstream culture. Part four illustrates this ancient tradition; it is labelled “Themes of Culture” and contains the poetic genius of great minds from Hafiz to Maulana Rumi and beyond. The importance of religion to the average Afghan is easier to understand when keeping in mind the fact that the cultural milieu in which he/she has been raised is centred around religion and spirituality. The medieval works of poets like Hafiz, with their emphasis on mysticism and the desire to be re-united with God, are well known amongst the Afghan people. Poetry permeates every Afghani class and is not circumscribed to the educated elite, as is often the case in western cultures. The function of poetry in Afghani life is as pertinent today as it ever was in the past.

Images of Afghanistan holds many examples of cases where the wisdom of medieval poets is called upon even in recent times. The editor recounts a personal experience where he witnessed a woman awaiting her brother’s trial in an Afghan court of law with a pocket-sized Diwan-e-Hafiz in her hand, illustrating the importance and appeal Sufi poetry holds for the Afghani people even today.

What makes the book particularly interesting is the artistry with which the editors have selected material, and the juxtaposition of higher forms of art with the seemingly banal. For example, alongside Maulana Rumi’s poetry, children’s Pashto nursery rhymes have been published. The content of these rhymes is out of the ordinary and unlike those common in the West. The editors have chosen nursery rhymes regarding fallen rulers, political leaders — both popular and unpopular — and the political state of affairs of the country. The overtly political rhymes reflect the receptiveness of Afghan adolescents to their surroundings, furthering the idea that the Afghan youth are sensitive and intelligent. Aside from nursery rhymes, the tales of Mullah Nasruddin are another example of the higher forms of storytelling enjoyed by Afghan children. Mullah Nasruddin, with his tomfoolery and false wisdom, offers a multitude of profound lessons in the disguise of children’s tales. The stories have permeated foreign markets as well, and variations of the traditional tales told to Afghani children can be heard all over the subcontinent.

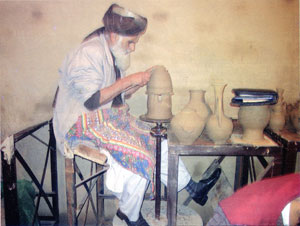

After the discussion on poetry, parts five and six inform the reader of the many traditional art forms of the region, such as wood-carving, pottery and handicrafts. The photographs accompanying the chapter on handicrafts are particularly well chosen and well placed as they illustrate the intricacy and artistry that the editors write about. The craftsmanship that goes into each piece of work is remarkable and will undoubtedly be appreciated by international buyers if marketed properly. One hopes this book will open new avenues for international appreciation of Afghani goods.

The last section, “Potpourri,” speaks of recent literary and artistic developments taking place in Afghanistan and the fusion between western work and Afghani work. It highlights the growth in the industry locally and the growing acceptance and infiltration of Afghani talent the world over. An example of East-West Afghan fusion discussed in the book is the international best-seller The Kite Runner (which was also made into a motion picture) by US-based Afghani author Khalid Hosseini. The editors offer an interesting discussion on this book and the flurry of excitement that surrounded its release. The Kite Runner is used as a gateway to discuss cinema in Afghanistan. While the film industry is virtually non-existent in the region itself, individual filmmakers from Afghanistan have ventured abroad to make movies. These small-scale projects may not be commercially successful but they do reflect the efforts and the desire of the Afghan people to break into a new form of artistic expression. The endeavour to bring cinema to Afghanistan and the growing work to make it a viable field reflect the Afghan aptitude for the arts. Loewen and McMichael have carefully picked such examples to illustrate their point that Afghanistan holds a wealth of culture and character that the rest of the world could gain much from, both in terms of entertainment as well as enlightenment.

Images of Afghanistan makes for an enriching read where the reader puts down the book feeling hopeful for the nation and all its talent. It is successful in its mission of depicting a softer side of Afghanistan and provides the first-ever overview of art and literature of the region, thereby giving a key insight into the complexities of Afghan culture. The book offers the opportunity to learn about Afghanistan in a new way, divorcing the nation from the harsh paradigm within which it is usually discussed.

This review was originally published in the October 2010 issue of Newsline under the title “Afghan Flavour.”