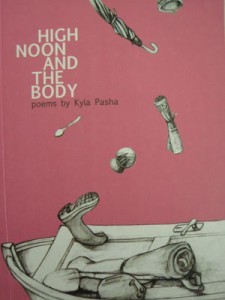

Book Launch: High Noon and the Body

By Ilona Yusuf | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 14 years ago

Kyla Pasha’s first collection of poems High Noon and the Body was launched at Kuch Khaas in Islamabad, early December.

Kyla Pasha’s first collection of poems High Noon and the Body was launched at Kuch Khaas in Islamabad, early December.

The launch featuring readings by the poet herself and two others, began with Kyla’s exhorting her listeners to respond in the subcontinental fashion ‘Wah, Wah.’ Although such punctuation from the audience isn’t customary in English readings, it was one more in a chain of cross cultural references that have become the norm in today’s world. The resounding chorus of ‘Wah, Wah’ testified to the keen enjoyment of the large audience.

High Noon and the Body, the title of one of the key poems as well as of the collection itself, is unabashedly confessional — a journey of self-discovery. How do we define ourselves — through others, through learning the truth about oneself. How do we reconcile the conflicting elements within us — with the consciousness of God, trapped within us?

Here is love poetry in which the poet and her subject become virtually inseparable. But it isn’t conventional love poetry. It’s as if Pasha wants to take on all the injustice in the world and challenge her reader. Her conviction, that poetry is a conversation between poet, subject and reader, is clearly visible in the poem, “The Poet at Every Fest”:

If you were not looking, I would not

be here. Caught in the cross

fire of defiance and desperation, I

am poet… speaking

my own demons like they’re yours,

my own anger like it scores an

orange alert…

If you were not looking, I would

almost have nothing to say.

Although the poems in this collection use simple language, as in “Post-it Notes on Your Door,” where the tone is naive as a child’s, it is a deceptive simplicity:

Sometimes

I love you and I don’t know where

to take it — you live too far

and there are lions.

“Trip Back” talks about invasion, trauma, and can be read on several levels such as the invasion of a nation, the mind, or the body. The seemingly domestic situations are superficially commonplace, concealing complex, dark realities:

I sent up flares, I was invaded,

now I must tidy up the room.They came for me, an act

of kindness. They left a mess

in my back yard. They left

a warning: The things you must grow.

This is an original voice, confident and resonant. It has learned how to use the short line and almost colloquial language to express passionate conviction. There are names and concepts from religions other than Islam, but the personal dialogue with the creator embodies Sufi concepts, while her deep aversion to injustice embraces the personal and the political, inescapable realities of our time.