Past Forward

By Zahid Hussain | Reflections | Published 6 years ago

Pakistan’s politics has been moving in circles. Many times I feel that I am repeating my old stories – even the characters have not changed. In my more than three decades in journalism I have witnessed the country alternating between periods of ineffectual civilian administrations and authoritarian military regimes. But there has been no fundamental change in Pakistan’s political power structure. A small power elite has dominated the country’s political scene under both, civilian as well as military rule.

I entered the field of journalism in the heydays of General Zia-ul-Haq’s military rule. It was the best of times and the worst of times for the media. The draconian laws had stifled freedom of expression but alongside also given rise to a vibrant, resistance media. In those dark days there was hope of change. I never met General Zia and refused to receive my first APNS Award from him, so strong was my loathing for the dictator.

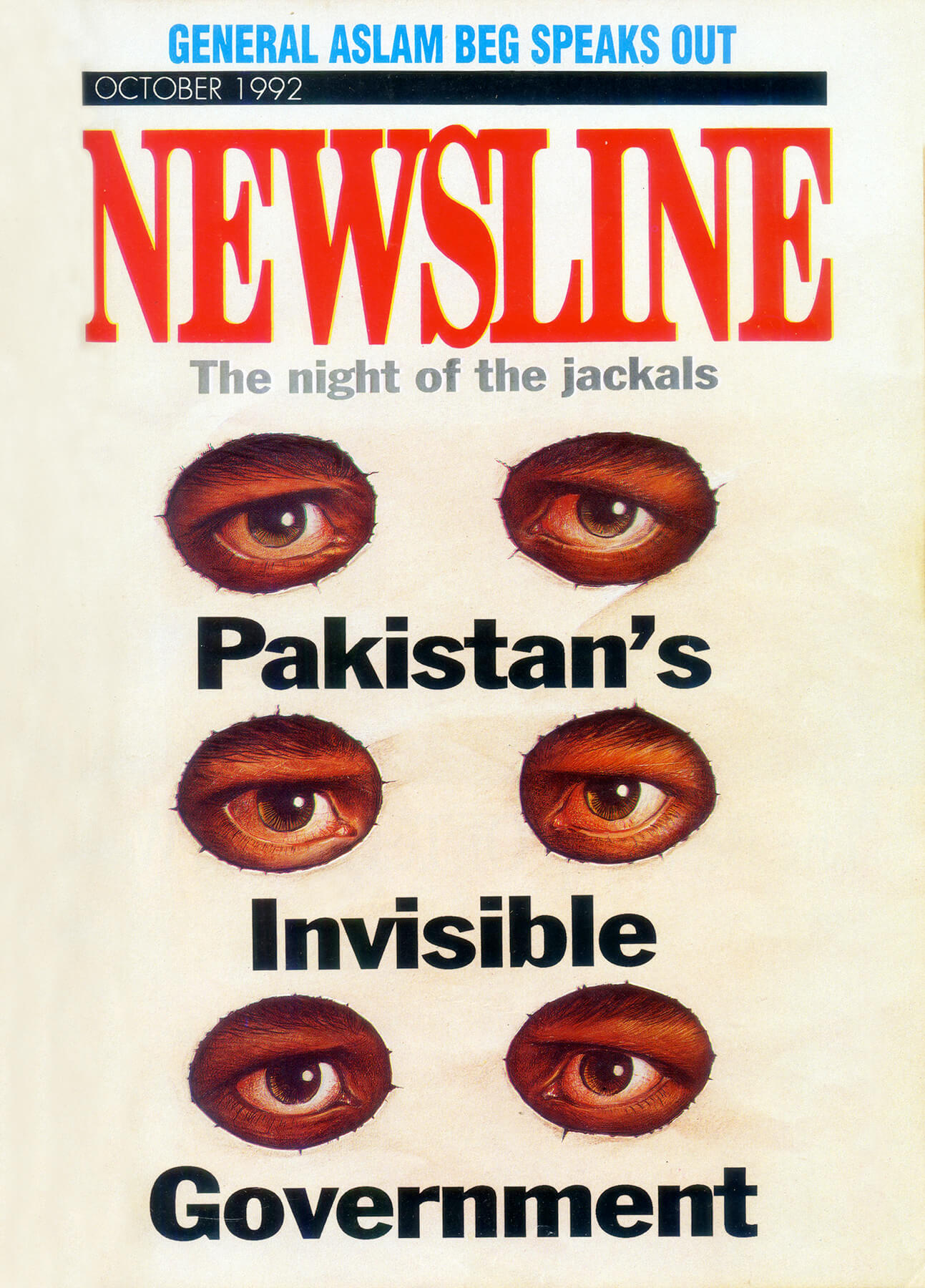

Coveri ng politics in Pakistan is like watching a soap opera that has all the ingredients of a thriller – suspense, excitement, treachery, backroom deals and of course, the omnipresent shadowy intelligence operatives. Our cover story “Pakistan’s Invisible Government” published in Newsline in early 1990 is a depiction of all that is wrong with the country’s politics.

ng politics in Pakistan is like watching a soap opera that has all the ingredients of a thriller – suspense, excitement, treachery, backroom deals and of course, the omnipresent shadowy intelligence operatives. Our cover story “Pakistan’s Invisible Government” published in Newsline in early 1990 is a depiction of all that is wrong with the country’s politics.

The 90s was a decade of musical chairs, with power alternating between the two post-independence leaders – Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif. Benazir Bhutto’s assumption of power in 1988, touted at the time as the dawn of a new democratic era, was in fact a transition from direct to indirect military rule. The formal restoration of civilian rule in 1988 did not reduce the ISI’s clout. A return to the barracks did not mean that the military’s structure of control and manipulation had been dismantled.

“Midnight Jackals,” the title of the other story, was the code name of the plot to oust an elected government involving the ubiquitous ISI. The plot failed but Benazir Bhutto’s first government could not survive for long. Benazir Bhutto found herself clashing directly with the army, when she removed General Hameed Gul from the ISI. She was not trusted by the establishment and many generals made it a point not to salute her.

It was in February 1990 that I met General Gul in Multan, where he was posted as the commander of Pakistan’s main strike corps, after being sacked from the ISI. It was the period when the army had just concluded a major war exercise called ‘Zarb-i-Momin.’ The General accused the Prime Minister of trying to make peace with India and questioned her patriotism. “By conducting the exercise we have blocked her designs to undermine Pakistan’s defence,” he said.

The story didn’t end there and yet another plot ensured the victory of the pro-military coalition led by Nawaz Sharif in 1990. The military’s decision to rest content with dominance, rather than direct intervention, was based on a careful calculation of the advantages and disadvantages of playing arbiter in Pakistan’s highly polarised and conflict-ridden political arena.

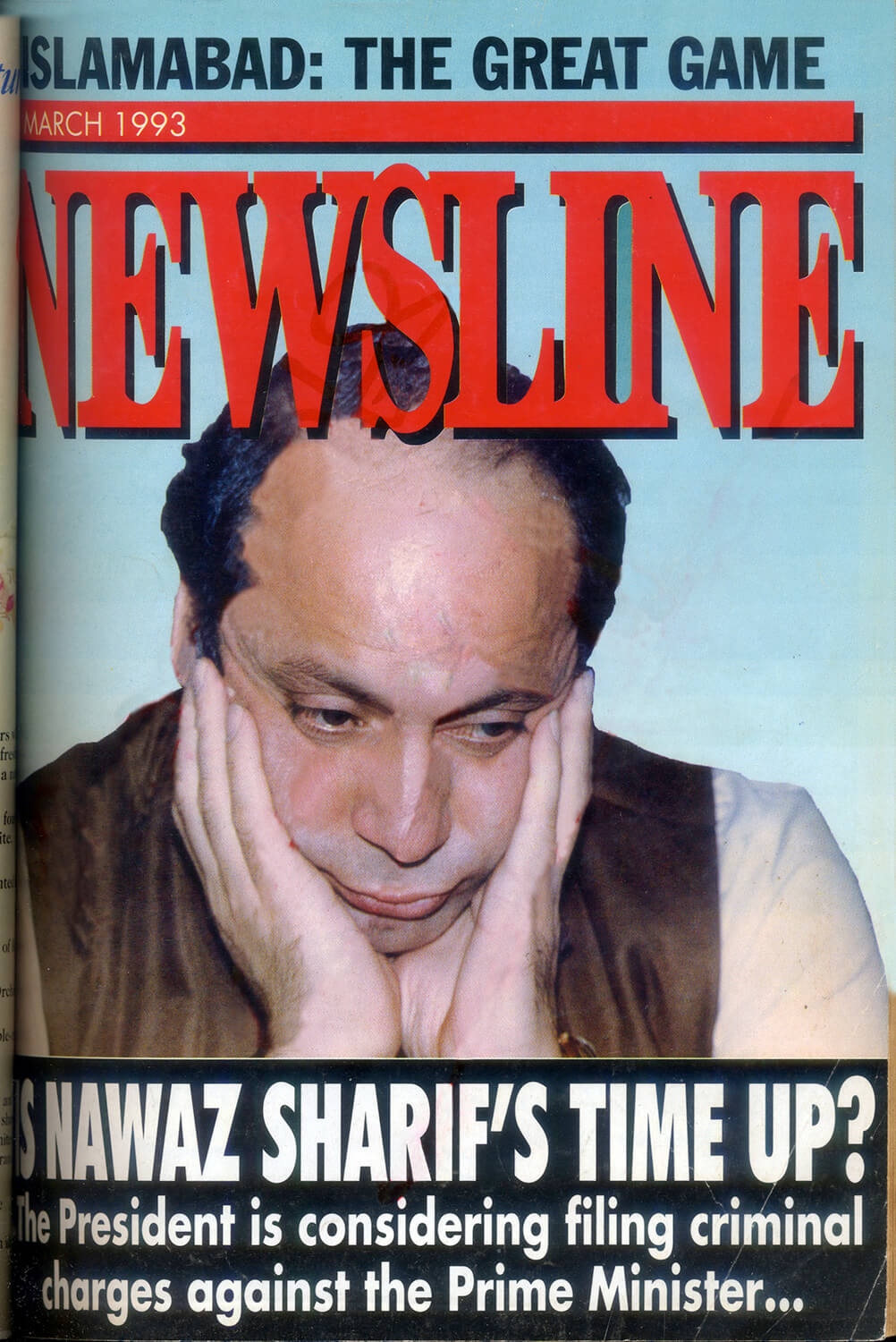

Sharif assumed power with far greater advantages than his predecessor had enjoyed. But this harmony was not to last: He sought to wear down constraints on his power imposed by his old patrons. I remember meeting President Ghulam Ishaq Khan at the peak of his conflict with Sharif. He was very candid that he was not going to spare him. That made our cover story ‘Nawaz Sharif’s Time Up?’ that won us the APNS award for the scoop of the year.

Sharif assumed power with far greater advantages than his predecessor had enjoyed. But this harmony was not to last: He sought to wear down constraints on his power imposed by his old patrons. I remember meeting President Ghulam Ishaq Khan at the peak of his conflict with Sharif. He was very candid that he was not going to spare him. That made our cover story ‘Nawaz Sharif’s Time Up?’ that won us the APNS award for the scoop of the year.

Sharif was not to be trusted, so it was now Benazir Bhutto’s turn to form the government again. Bhutto returned as Prime Minister for the second time in November 1993, just three years after her unceremonious exit. The situation was much more favorable for her government this time, with a president from her own party and a sympathetic army chief. She had learnt some lessons from her first tenure and treaded a cautious path. In her first interview with me after a few months in power, she also indicated that her husband Asif Ali Zardari would have no role in the government, but soon after he was inducted in the cabinet.

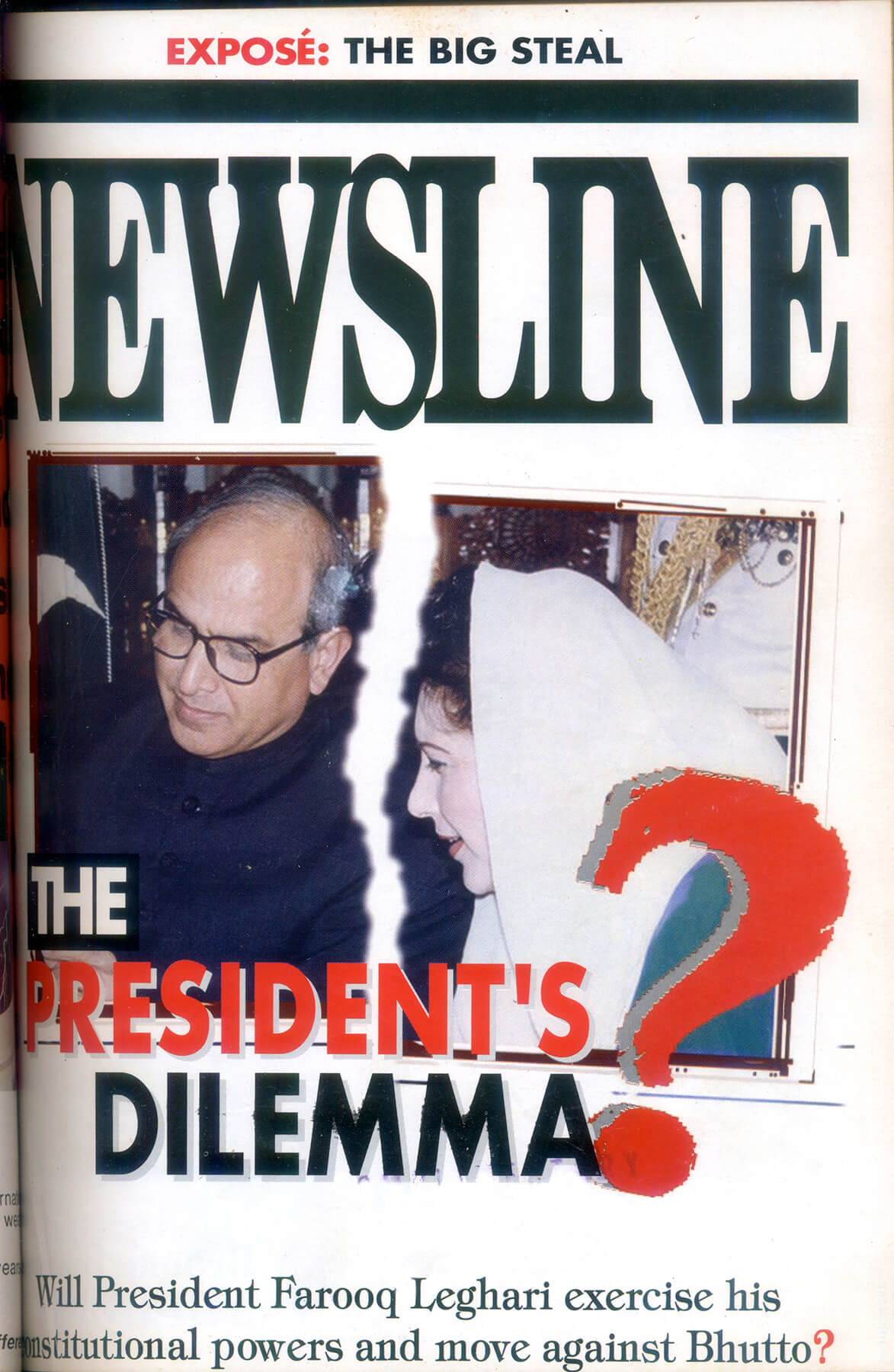

The clash with President Farooq Leghari finally led to BB’s downfall. Weeks before her ouster I had an informal meeting with President Leghari for two hours and got a clear sense that he was going to act. I did a cover story in Newsline titled, “The President’s Dilemma?” As soon the magazine was out, I received a call from the Prime Minister’s office, contradicting my story. Surely the PM had not realised the gravity of the situation. Three months later, the President dismissed his own party’s government.

Among all the Pakistani leaders I had interacted with during my journalistic career, Benazir Bhutto was by far intellectually the most astute and had a great capacity to take criticism. But her biggest failure was her inability to control the rampant corruption involving people around her. It was her husband who was largely responsible for her conflict with President Leghari.

Now it was Sharif’s turn in power. This time he came with an unprecedented two-thirds majority, often described as a “heavy mandate.” But half-way through his second term, his confrontation with the military led to his downfall yet again. This time it was direct military intervention. He was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. Intervention by his powerful friends in the Middle East got him out of prison and flown to Saudi Arabia. How the deal was made was one of my scoops for Newsline.

It was the fourth time in eight years that an elected government had been dismissed less than half-way through its term. Weak democratic institutions, lack of a democratic political culture, the politics of patronage, ineptitude of the political leadership and the military’s involvement in politics all contributed to the continuing crisis of democracy in Pakistan.

A week after the military coup in October 1999, I flew from England, where I was a visiting fellow at Cambridge University, to Islamabad to interview General Musharraf. It was the first of my several interviews with the military ruler, including one for the cover story on him in Newsweek in 2002. During a dinner with the family, the General looked embarrassed when his mother said that compared to his two other brothers, Musharraf didn’t do well academically. “I wouldn’t call myself bad in studies,” General Musharraf started to say but his mother cut him off: “You were average.”

Subsequently, I became persona non grata when I wrote about the military’s power and perks. He was furious. But at the fag end of his presidency I met him again. I could see that a change had come over him in the nine year period – he looked depressed, knowing that his days in power were numbered.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.