From Journalism to Parliament

By Nafisa Shah | Published 6 years ago

I was not always the chador-clad, hard-edged politician debating with political counterparts on talk shows, or making passionate speeches on the opposition benches of the National Assembly or cutting ribbons at the launch of development schemes in my constituency. I had another life.

Once u pon a time, ages ago, I lived and worked as a firebrand and socially charged journalist. From 1989 to 1996, I worked at Newsline, rising from a junior staffer’s post to become one of its core team, and on the way winning an APNS award for best story and an international UNEP award.

pon a time, ages ago, I lived and worked as a firebrand and socially charged journalist. From 1989 to 1996, I worked at Newsline, rising from a junior staffer’s post to become one of its core team, and on the way winning an APNS award for best story and an international UNEP award.

All this rising and shining was due to the late Razia Bhatti, who was a natural at team-building and led a group of journalists who split from Herald to create Newsline, an independent magazine, as an example of honest, fearless, high quality journalism and editorial content.

Conscious that my father was a Peoples Party stalwart, then serving as the Chief Minister Sindh, I drew boundaries from day one, deciding I would not do political reporting but confine myself to social and environmental journalism. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, environment was niche journalism and following on the heels of writers like Ameneh Azam Ali, whose life was tragically cut short by cancer, I wrote on wildlife, national parks, on urban decay and cultural and environmental protection.

Journalism for me was empowering, exciting and challenging and best suited to my restless temperament. It was a journey to the discovery of the possible. I traversed hidden, unmapped, uncharted territory, extracting the most precious of stories possible, in the tradition of Razia Bhatti’s journalism.

I explored Karachi’s old bazars, unearthing Sarafa bazar, Khajoor bazar and the timber markets in the process. I wrote on the stuntmen and film extras of Pakistani cinema in the ’70s and ’80s, on Karachi’s fisherfolk and the degradation of their beautiful coastal area, and the dying breed of brass band musicians in old Karachi.

I travelled to places often with my colleague Hasan Mujtaba, who had a penchant for bringing out one thousand and one night stories. I went to Tharparkar with Hasan to cover the seasonal drought and the massive migration, and made a historical journey to unravel the buried history of the Hur Movement. I also did stories on social issues, the most important being an exposé on violence in the name of honour in Upper Sindh.

Celebrating women’s day amid a charged crowd in Lahore in 1995.

But my transition to becoming a political person was not straight out of Newsline. From Newsline I moved on to academic life, with the aim to research the honour-based practices in Upper Sindh, first as a Reuters fellow at Green College, Oxford in 1998 and then as a Chevening Scholar at Wolfson College, Oxford University where I did my Masters in Social and Cultural Anthropology and later enrolled as a PhD student.

When I returned to Pakistan from the UK to venture into anthropological fieldwork, my party and family called upon me to contest a local government election for District Nazim, in my home district, Khairpur Mirs. It was May 2001 and local government elections had been announced under General Musharraf’s military rule. There was a competition between two candidates in the party who were pitted against one another, and my nomination was the middle way to resolve the party dispute.

In Khairpur’s largely male-led political landscape with two of the largest gaddis, of the Pir of Ranipur and Pir Pagaro, and a former ruler of the State, the announcement of an unknown woman candidate for the district nazim post was a jaw-dropping surprise for everyone. Some thought I was a foreigner, others were worried about how a woman would deal with the political challenges in the district, and many were betting on how soon I would flee the area. Most just thought it would actually be Qaim Ali Shah’s seat where my appearance didn’t even matter.

I was personally very reluctant to enter politics as it would mean abandoning my PhD at Oxford, but my father assured me that it would only be a formal role, and after contesting elections, I could go back to Oxford, returning only occasionally to ‘sign papers,’ implying that like many women in politics I would be a proxy for male politicians, serving to fill a gap till the situation changed and a man returned to the seat. That was an acceptable deal and I agreed to contest elections on the condition that it would be a short stint – like a few weeks – till I went back to Oxford.

But on the day after winning elections, I found myself in the Nazim’s office – and alone. Of course, all the family and well-wishers who had promised they would do all the work and I would only occasionally sign papers had vanished.

My office was filled with dozens of people, many men and women, mostly very poor, carrying typed or handwritten applications, with modest requests, seeking jobs, wanting a girls’ school, water supply for their village, a brick pavement, zakat funds, or calls to the SP’s office to resolve disputes.

I noticed that unlike the election hype casting doubts on the ability of a woman to handle tough local politics, the people in front of me were not concerned about whether I was a woman or a man or any gender at all, they just wanted their basic problems solved.

I knew t hen that I could never be a mock Nazim or signing authority only. It was no more a pledge between my family, the party and me. The third party, the most important one was the people. I knew then I could not leave them. I would be there for them, tied with them intimately, in their lives, in their happiness and in their tragedies.

hen that I could never be a mock Nazim or signing authority only. It was no more a pledge between my family, the party and me. The third party, the most important one was the people. I knew then I could not leave them. I would be there for them, tied with them intimately, in their lives, in their happiness and in their tragedies.

That was 18 years ago. These 18 years of my political life I have served the party that honoured me with a ticket to contest local elections and the people of my area with equal commitment.

My reincarnation as a politician has not been an easy one. From a vast and free life of endless possibilities to a chador-clad reserved presence, where I had to watch my every word, act and move was indeed restrictive and suffocating and there were days I just wanted to run back to my previous life. But what held me back was a sense of purpose – to solve problems that people brought to me, and the knowledge that my one phone call, one chit or signature could change many lives. So I stayed put.

In my constituency I happily became everybody’s sister, ‘Adi’. This was a mark of respect and a symbolic way of circumscribing my space as a female politician. But my social life came to a halt. I spent the first four years of my political life as the reclusive Nazim of Khairpur where my social life was all about the people of Khairpur, whom I served with passion and faith. I built low-cost schools, roads, dispensaries, promoted the arts, worked with artisans. I tried to resolve bloody tribal disputes between communities. All this work did get me some more accolades: I was nominated as a young global leader by the World Economic Forum and I was nominated as one of 1000 women for a collective Nobel Award by a Swiss organisation.

These 18 years have been pure hard work. From visiting villages and schools in my constituency in Khairpur, to the parliament in Islamabad, writing and editing laws, this has been an exhilarating journey. The Pakistan Peoples Party gave me all the space to grow and take my politics where I wanted it to go. Powered by women like Shaheed Benazir Bhutto and Begum Nusrat Bhutto, it is easily the best party for the women of Pakistan.

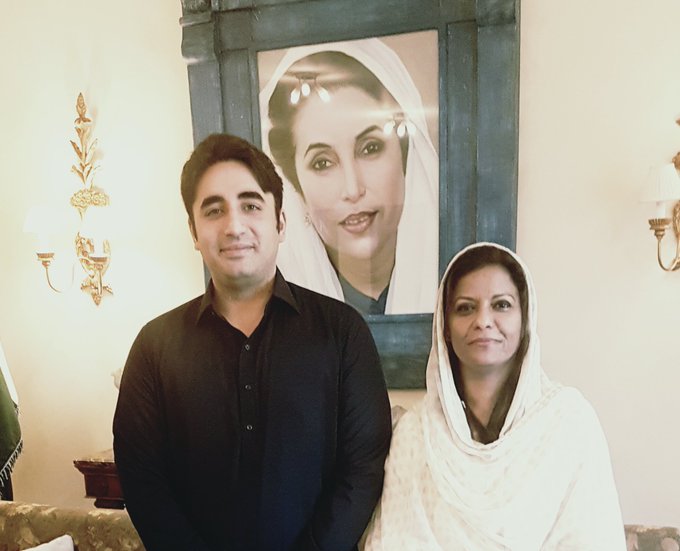

I learned later that my entry into politics was Shaheed Benazir Bhutto’s choice. We had both agreed that once I finished my PhD, I would be joining her personal team, but alas, with her tragic assassination, this could not be. Today her son and Party Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has fulfilled that understanding, entrusting me with the Central Information Secretary’s post. My commitment is unwavering and my passion to work to change peoples’ lives and make our country a better place has only grown with time.