It’s in the Idiom

By Sumbul Khan | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 16 years ago

Sadia Salim’s recent works at Koel Gallery evoke the idea of transience through everyday objects with which one makes brief but frequent tactile contact and then discards. Water bottles, yogurt containers, corrugated paper that wraps cookies and food cans are all part of the perpetual ephemerality of our 21st century realities.

Interestingly, casting such objects as ceramics lends them a permanence which they are otherwise denied. Direct reference to objects in her personal space is a new intervention in Salim’s oeuvre. As a ceramist for whom process and perfection of technique are almost more sacred than the product, this current departure stems from the set of facilitative limitations she encountered at her residency in South Africa recently, which compelled her to seek a directional shift. From a visual culture critic’s vantage, this has been most fortunate, for here we encounter her personal narrative and commentary on contemporaneity in a more accessible idiom.

The concept is not as disjointed from her long-standing concerns as it may first seem. Her bowls and vessels put together as ‘Caravan,’ also on display in this exhibit, were as much about the uncertainty of time and place as the more recent works. Oriented along off-vertical axes, each of this set of ten vessels is open to twirling in all directions, while maintaining a rhythmic unity among themselves. Whereas these vessels operated as personifications and portrayed internal dilemmas surrounding life and mortality, there is a very earthbound physicality in the recent works. In a way the idea has been externalised and having gone previously from the inside out, Salim now seems to be finding her way from the physical manifestations of every-day existence back to the dubious un/reality of this space which is in constant flux.

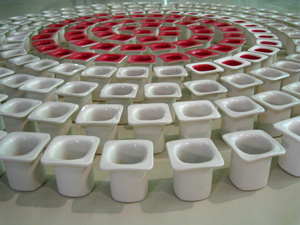

“The city … its chaos influencing mind, body and soul, desire to find peace, wishing away reality” is a 7 x 7 configuration of white porcelain bowls with crystalline interiors. At its centre is a bowl with a flat, virulent red interior. Although the mathematical blueprint aspires to lend order to its components, the off-center bowls continually defy that structure and the artist’s desire to keep them tilted one way, as opposed to another, is thwarted time and again. The serenity of the colour palette gives way to queasiness as the bowls turn into eyeballs staring back at the viewer through their crystalline irises and drive home the paranoia of living in a city at a time when everyone is potentially threatening, possibly dangerous. In the context of this show it seems to be a wishful inclusion that hopes that this predicament of the city dweller is as transient as the other things that surround us.

“The city … its chaos influencing mind, body and soul, desire to find peace, wishing away reality” is a 7 x 7 configuration of white porcelain bowls with crystalline interiors. At its centre is a bowl with a flat, virulent red interior. Although the mathematical blueprint aspires to lend order to its components, the off-center bowls continually defy that structure and the artist’s desire to keep them tilted one way, as opposed to another, is thwarted time and again. The serenity of the colour palette gives way to queasiness as the bowls turn into eyeballs staring back at the viewer through their crystalline irises and drive home the paranoia of living in a city at a time when everyone is potentially threatening, possibly dangerous. In the context of this show it seems to be a wishful inclusion that hopes that this predicament of the city dweller is as transient as the other things that surround us.

On a purely visceral level ‘Transience I’ is, to me, one of the most pleasing sets of work. The transformation of porcelain into paper-thin corrugated containers harks to the brittleness of old age. The act of eating biscuits out of one of them and crumpling them before throwing them away resonates with the way the elderly are treated in urban spaces fraught with inflation and increasing poverty. They bring back news coverage of senior citizens being abandoned at Edhi Centre by children who simply cannot afford to keep them anymore. The irony of eating imported cookies out of corrugated paper trays, while this kind of hopeless desperation surrounds us, can be quite disturbing.

Salim pertinently notes that Warhol’s own stated reason for his soup cans was that they were part of his own reality and so, too, is the case with the objects she uses. Yet, Warhol’s work can be read as testament of the mass-produced, ready-made reality of his century, which was a reality shared by a vast majority in his time. Similarly Salim’s work too, though personal, can be queried for its relationship with the world around her, and in this case one finds that the equation is not as general as the kind seen in Warhol. The city we live in remains intensely class-divided and the objects seen here are ordinary objects for only some of us who fall above a certain income bracket. Although the greater population can readily relate to bottled water, it’s still not an item of regular consumption for them. Perhaps this, then, is the soup that can be reconfigured in the 21st century Pakistani context — a symbol of class difference, of unequal privilege.

Salim pertinently notes that Warhol’s own stated reason for his soup cans was that they were part of his own reality and so, too, is the case with the objects she uses. Yet, Warhol’s work can be read as testament of the mass-produced, ready-made reality of his century, which was a reality shared by a vast majority in his time. Similarly Salim’s work too, though personal, can be queried for its relationship with the world around her, and in this case one finds that the equation is not as general as the kind seen in Warhol. The city we live in remains intensely class-divided and the objects seen here are ordinary objects for only some of us who fall above a certain income bracket. Although the greater population can readily relate to bottled water, it’s still not an item of regular consumption for them. Perhaps this, then, is the soup that can be reconfigured in the 21st century Pakistani context — a symbol of class difference, of unequal privilege.