Cover Story: PML-N’s Year to Nowhere

By Syed Talat Hussain | News & Politics | Published 11 years ago

It is about as comprehensive a document as can be prepared by a group of dedicated researchers. Spanning 178 pages, comprising figures, charts and an impressive reservoir of data and statistics, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) one-year performance sheet leaves nothing to the imagination. Loftily named the National Agenda of Real Change, the paper reads like a fairy tale of astounding feats by magical beings that you might find in the Harry Potter series, but almost never in real life.

According to these claims, Pakistan’s terrorism problems in all their awfully complex dimensions are all but solved; its education, health, infrastructure, housing sectors etc., are at a fantastic take-off point; the economy stands revived; business and employment opportunities have risen manifold; less developed areas have become the focus of policy as never before; sugar, urea, gas, coal, IT and other such commodities of collective use and application are now breaking forth in abundance; governance structures have markedly improved; national institutions, once teetering on the brink, are now on the way to becoming robust again.

Miracles in the realm of foreign policy, too, are spreading across the world, leaving only frozen bits of territory on both poles of the globe. India, Afghanistan, China, Iran, the United States, Turkey, Russia, ASEAN, the Middle East, Central Asia, the European Union, the United Kingdom, the African countries, Canada, Latin America — these are all part of the successful diplomatic ventures undertaken by the government in a year. This is dazzling stuff even by the legendary standards of propaganda that the Ministry of Information, Broadcasting and National Heritage conjures up in projecting official narratives.

Topping up this radiant picture of a happy land under the N-League’s first year in power is the more recent development of the prime minister’s visit to India on the eve of Hindu-hardliner Narendra Modi’s swearing-in as prime minister. Read the official description and you may think that these nuclear-armed adversaries are on their way to becoming best friends. “As I take leave of this historic city, I do so with a strong sense that the leaderships and the peoples of our two countries share the desire and mutual commitment to carry forward our relationship, for the larger good of our peoples,” is how Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif articulated his take on the outcome of the visit. Mariam Nawaz, the prime minister’s daughter who is being groomed as a potential foreign minister, was tweeting feverishly on the eve of this meeting, boasting how “foes” have become friends — thanks, of course, to the leadership of her father.

However, when examined more closely, some of these official claims ring hollow, others are downright ridiculous and only some are partially true. The fact of the matter is that Pakistan, in the Sharif government’s first year, has remained troubled and misgoverned. There has been much trumpeting about democracy, but little delivery of services. From Khyber to Karachi and from Turbat to Gilgit to Kashmir, there is hardly any shining example of success- inspiring confidence that the country is on the right track.

This is primarily because of anaemic economic conditions. The government says that the growth rate is likely to jump up to 5.1 per cent in the future, but for now it is struggling at around three per cent. And this is in a sector that the Sharifs have always argued is their strongest qualification to rule the country. The economy is operating under a thick pall of chronic violence and instability which the government has done little to address. Heavy borrowing from the banks by the government itself has resulted in low lending to the private sector and small businesses. Growth figures are primarily shaped by constant and questionable injections of international loans and one-time donations with tough pre-conditions. Budget deficits are still large, and an equitable taxation regime is a far cry. Other than a handful of big businesses, real estate tycoons and beneficiaries of generously-funded mega projects, there aren’t many in any sector who see a bright financial future. Capital outflows continue apace. Corruption is rampant, and so is poverty and disease. But what is worse, other than the constant refrain of “growth-led strategy” heard from Finance Minister Ishaq Dar, is that there is no coherent vision that underwrites efforts to stabilise the economy. Ishaqism is Adhocism. This is the sum-total of Sharifonomics.

The Sharifs’ trump card to overhaul the economy on a mega scale is trade. No official meeting is ever complete without energetic references to the country being a corridor for a massive flow of goods and services across continents. However, this intrinsic potential of Pakistan’s geographic locale presupposes a stable neighbourhood in which Pakistan is a strategic pivot. For now the immediate surroundings — Afghanistan, Iran and India — are in a state of flux. With two new governments in Delhi and Kabul, it is difficult to predict which way the gods are going to swing the pendulum for Islamabad — towards goodwill and peace or bitterness and disharmony. As the US pulls out of Afghanistan, China faces the rise of fundamentalism in its south and the Middle Eastern monarchies struggle to save their thrones, Pakistan is in a geographic tension zone whose dynamics would require a high degree of vision and leadership to turn challenges into opportunities.

PML-N leaders insist that their long-standing experience gives them the expertise to manage Pakistan at this tricky juncture. They cite the prime minister’s tour of India as an example of his long view of Pakistan’s place in the comity of nations. “Conflict is what ails us. We need to break this cycle of mutual acrimony and violence. Whether with Afghanistan or with India, we must make peace for progress. That is what the government has done. You will see the results in the years ahead,” says a senior government source who had accompanied the prime minister to Delhi.

Yet peace with India is not an easy deal. It has become truly complex on account of the way the government has gone about the whole business of peace. Sharif’s visit to Delhi had only half-hearted support from the military’s top brass. Military sources argue that the visit sent the wrong signals about how far Pakistan was willing to go to accommodate Indian demands.

One senior level military source explained these reservations in the following words: “The context of this visit is based on many rounds of secret diplomacy whose outcome is basically settlement of most issues on Indian terms. Even for Kashmir, there is a suggestion of its practical division. The process through which this secret diplomacy has been conducted has been completely exclusive. We were taken into the loop after a long time and, then too, only partially. This is too serious a business to be decided like this. Every institution’s input should go into it. There should be debate and discussion in place of dead-of-the-night deal making.”

Even foreign office officials, normally seen as dovish on India, are upset. “Ask Tariq Fatemi,” was the abrupt response of a senior foreign office source, wishing not to be named, when asked about the four-item agreement that former foreign secretary, Shahryar Khan, has worked out with S K Lambah, the Indian back-door diplomat. This formula is the framework that Prime Minister Sharif is using to engage with Delhi. Clearly, the Sharif camp is not functioning as a transparent entity where critical areas are open for debate. It is virtually a family affair where decisions are made by a handful of close business associates and advisors who form the Sharifs’ charmed circle.

The PML-N has an explanation for moving at breakneck speed on the zigzagging road of trust-building with India. “We have inherited a broken system. We have to do things quickly or else they will never be done. The previous government invested only in corruption, and the one before that (General Musharraf’s) in unravelling the constitutional order. We have to repair both and we have to do it swiftly. The world is acknowledging that our direction is right and so is the progress for the first year,” says a member of the Sharif team who deals with image-building of the government in the media.

The “international acknowledgement” of heading in the right direction is actually a code for favourable statements from Washington and London. Indeed diplomats representing the US and UK feel that, compared to the previous government, this one is a considerable improvement. However, they qualify their praise with the quip that “that’s not exactly a comparison to be proud of.”

The real problem with the Nawaz government is that while the country has become remarkably complex, it continues to rule according to the manual it had prepared in the early ’90s. Among the many convoluted rules of the ’90s manual of applied politics, the top three were: tall claims jack up small gains; political power is a family affair; and decision-making is a solo flight. The Nawaz Sharif of 2014 is really Nawaz Sharif circa 1997.

This inclination to treat opaqueness as the best form of decision-making is visible even in relatively smaller projects. At a cost of Rs 44 billion, or US$ 500 million, the Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metro Bus Project has caused much controversy. It was decided in Lahore by Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif and implemented on the ground upon special instructions from his elder brother, the prime minister. Unlike the Lahore Metro Bus project (which is to now be overtaken by a train project), the legal requirement of conducting an Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) has not been carried out. Alternative transport systems, such as one proposed by the Asian Development Bank costing just Rs 4 billion, have been disregarded and legal requirements under the Environment Protection Act of 1997, such as holding public meetings, have been complied with in a pro formamanner after the bulldozers and diggers had already started to steamroll the initial stage of the project.

“What was the hurry? Who are the beneficiaries of this project? How has this been decided? We need to know,” says Afrasiab Khattak, head of the Senate Human Rights Committee and a senior leader of the Awami National Party (ANP). Asad Umar, a senior member of the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI), tried to challenge the project in the Supreme Court, but his petition was returned on the grounds that the co-petitioner, Senator Mushahid Hussain, had already moved court on this.

Consider, also, the bizarre manner in which the government has pursued talks with the Taliban. After months of foot-dragging, peace committees and much media hype, the chapter of negotiations has been quietly closed (even though officially it is still open). The army has finally moved its long-stationary ground forces in North Waziristan that are engaged in close combat with militant groups, who are getting a pounding from the air as well. However, just as no one knows what really transpired during the negotiation process, there is little information available about what caused the option of force to become operational.

This goes to the bottom of the struggle of survival that increasingly characterises the Nawaz government’s conduct and the haphazard way it is governing the country. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif wants to go solo on everything and expects everyone to follow him. No questions asked.

“We have been pleading with Mian Sahib that he should have a more focused approach to governance and major initiatives, go slow but steady, and make use of the opportunity that a completely foolish opposition and circumstances have handed us to create history by steadily performing in power but through consensus,” says a frustrated member of the PML-N, who at one time was part of the main hierarchy of the party but has been sidelined for his outspokenness.

“Every time I would say this to the prime minister his hangers-on would jump in and suggest that the best way forward for him to leave a great legacy was through memorable initiatives. Mian Sahib loves such talk. He is a man in a hurry, but does not have a clear road map before him,” says the PML-N member.

Among the many jokes about the Sharif government doing the rounds in Islamabad is one which suggests that if Nawaz Sharif were to become the prime minister of Britain, we would see the takeover of 10 Downing Street by the army. Such is his tendency to invite trouble.

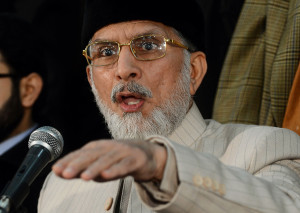

Jokes aside, at the end of its first year in power, the Sharif government is confronted with a deepening political crisis, and talk of mid-term polls dominates not just the capital’s drawing rooms, but also the streets. While Imran Khan has recently distanced himself from any kind of alliance, there is widespread speculation that the PTI and Chaudhary Shujaat’s Q-League have teamed up with Dr Tahirul Qadri to launch mass-scale street protests. On the face of it, the protest is about charges of rigging in the last elections. In reality, the game is to lay siege to the Sharif government and force an early election. Rumours abound that this agitation has the backing of Pakistan’s military establishment. Journalists have received e-mails from unknown sources talking about a so-called Plan B, a supposed alternative to unabashed martial law.

Imran Khan, along with Sheikh Rashid, the Chaudhries and a crowd of followers that the Allama of Canada keeps in his pocket, will enter Islamabad after Eid-ul-Azha with, say, 500,000 people demanding fresh elections and they will not leave until the government agrees to fresh elections.

Imran Khan’s demand will be dangerously simple, democratic and impossible for the government to deny. Mian Sahib, if you claim to have won the elections without rigging, then why can’t you agree to fresh elections? Surely, if you won them before, you will win them again. A democratic party never runs from elections.

As the pressure mounts, with Aabpara and Imran working together, events will be pushed to ensure that the civilian government leans on the Pindiwalas for support. At that point, Nawaz Sharif may have no option but to either call for re-elections or stand belittled and cut down to size before the establishment.

If re-elections are held, massive rigging in favour of Imran Khan will take place and he will become an elected prime minister before the end of the year. But even if the PTI does not win a simple majority, it will be fine if the PML-N is made to lose 40 more seats, thus leaving the MQM, the PPP, the Chaudhries and Sheikh Rashid to form a coalition with the PTI with Imran as prime minister. In fact, the latter would be more preferable for the string-pullers, because it will help keep Imran Khan on a tight leash.

The whole cabinet, along with the prime minister, will be ISI-dependent, and Rawalpindi will, once again, control the government’s policies. Azam Swati and Sheikh Rashid, among several others, are all giving dates for the ouster of the current government. The Chaudhries are talking about mid-term elections. And the Imam of Canada is coming with his inqilab in July.

The whole cabinet, along with the prime minister, will be ISI-dependent, and Rawalpindi will, once again, control the government’s policies. Azam Swati and Sheikh Rashid, among several others, are all giving dates for the ouster of the current government. The Chaudhries are talking about mid-term elections. And the Imam of Canada is coming with his inqilab in July.

Neither the Supreme Court, nor foreign governments, will be able to question the legitimacy of this khaki change. It will be a military takeover, without the military being visible.

Clearly, someone close to the government is taking this agitation seriously. Even if these e-mails are a figment of someone’s rich imagination, there is no denying the fact that in the last month the government’s relations with the army have plummeted to a new low. The media crisis involving Geo’s allegations against the Director General of the ISI Zaheer ul Islam, in the wake of the attempt on the life of Hamid Mir, the channel’s senior anchor, has been aggravated by the nasty divide in the ranks of the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA). The regulatory body is split between pro-government and pro-army members, with one issuing the order to cancel Geo’s licence and the other overruling it in a matter of hours, followed by a show-cause notice to the first group from the government. Geo’s petition in the Supreme Court, still seen by many as favourably inclined towards the government, has evoked another exchange of fire between divided camps. Assuming that the court will provide Geo relief and restrain other channels from attacking their competitor, a vicious campaign against Justice Jawad S. Khawaja has begun alleging that he is partial to the complainant on account of his family ties.

Posters in Islamabad’s markets, from unknown “devotees of Islam” groups, insinuate that the judge is not fit to hear the case. Geo says the campaign is directed by the “angels” — a sly reference to ISI field operators. Reports suggest that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has clearly said no to the idea of shutting down Geo even partially. The merit of the decision aside, this has strengthened the impression in military circles that he was in on Geo’s massive and unprecedented assault on the ISI and the army, alleging that they kill journalists.

This crisis epitomises all the challenges that the Sharif government is confronted with as it starts its second year in power. It could have been averted by taking a firmer line in the initial stage, but they allowed it to aggravate and harden into an irresolvable puzzle. This trait of postponing tough decisions and taking actions in secret, has been the bane of the Sharif government during previous tenures and continues to characterise their behaviour even now.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s June 2014 issue as the cover story.

The writer is former executive editor of The News and a senior journalist with Geo TV hosting a prime time current affairs program.