Candle in the Wind

By Sama F | Inmemoriam | Published 12 years ago

Death may be inevitable, but there is always an element of shock and tragedy when it hits home. When news of Zahra Shahid Hussain’s death circulated across news channels and social media, everyone — whether they were acquainted with her or not, political or apolitical — mourned the tragic loss as if she had been one of their own.

Death may be inevitable, but there is always an element of shock and tragedy when it hits home. When news of Zahra Shahid Hussain’s death circulated across news channels and social media, everyone — whether they were acquainted with her or not, political or apolitical — mourned the tragic loss as if she had been one of their own.

A senior leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf who had been with the party almost from its inception, Hussain was by no means the first political party worker to have been killed in recent times; just two weeks prior, the ANP’s election candidate Sadiq Zaman Khattak was gunned down along with his four-year-old son when he was leaving a mosque in Bilal Colony.

And the city is filled with daily news of horrific accounts of violence. Always shocking. Always tragic.

But, as vice president of PTI in Sindh and formerly the president of the party’s women wing, Shahid was the first PTI leader to be killed in such a heartless manner.

She was a well-known educationist who had taught International Relations — a subject in which she held a masters degree from the London School of Economics — at Karachi University and, more recently, at the prestigious Lyceum and L’ecole schools for A Levels.

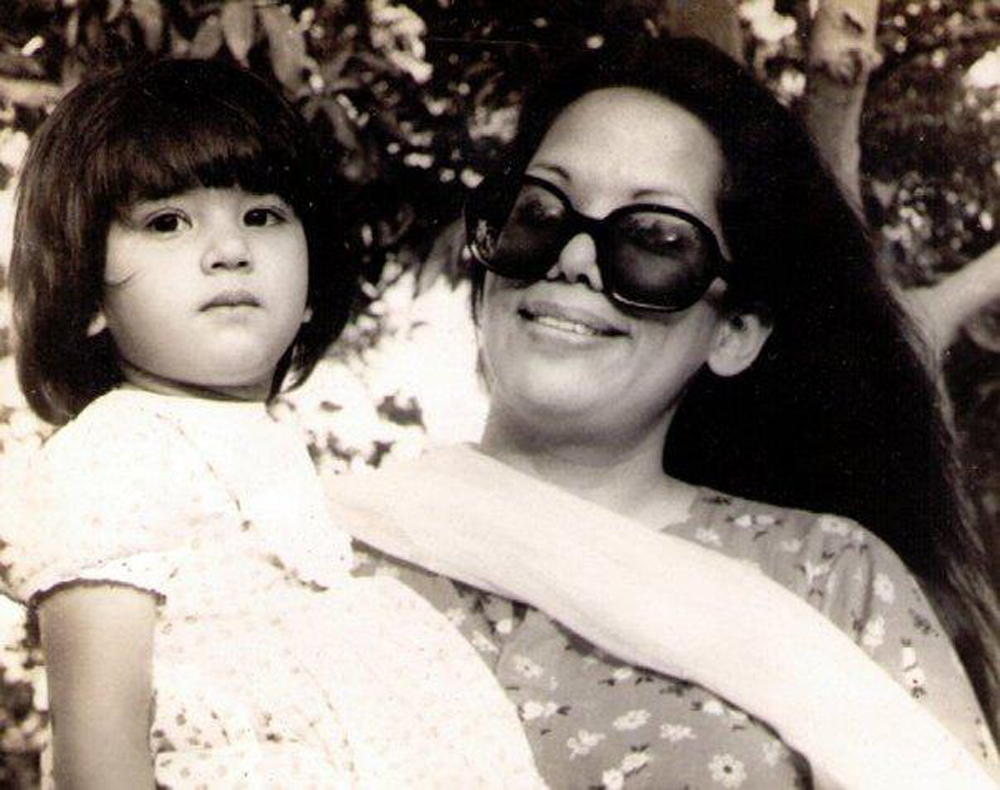

And, she was a mother. Not just to her two daughters, Basma and Nezihe Hussain, but she was also a mother figure to the relatively young PTI, who knew her as Zahra Apa. With all the machismo inherent in the party with the likes of Imran Khan and Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Hussain presented a softer image: generous, approachable, maternal.

She was also undeniably brave. One of her Politics students from L’ecole, Amna Liaquat, recalls how her students would insist she keep security guards, but Hussain would respond, “Jab likhi ho gi, tou goli kahin se bhi aa jaye gi.” Liaquat adds, “I admired her. Despite having a senior position in PTI, she never imposed her beliefs on us. She would always present us with both sides of the picture, and leave it to us to form our own judgements.”

Dr Arif Alvi has since dedicated his NA-250 win to his party member and friend who was shot in May 18, just a day before the re-polling of 43 booths in the constituency.

I had the chance of speaking to Zahra Shahid Hussain’s daughter, Nezihe, a few days after the tragic incident.

When I walked into their home in DHA, a woman named Farzana — who I soon learnt was Hussain’s sister — handed me a copy of that day’s Nawa-i-Waqt which carried a story on Hussain’s murder. The article drew parallels of her murder with that of another of Karachi’s socially conscious citizens, the late Parween Rehman of Orangi Pilot Project. Farzana mentioned that Zahra Apa had also worked with Parween Rehman in the past, back when Akhtar Hameed Khan was still alive.

The curtains were drawn and the room was dark, which added to the sombre atmosphere; the family was, of course, still in mourning.

When Nezihe walked in a few minutes later, she spoke of what she was going through in a calm and articulate manner, “Many people have lost their parents. Young children lose their parents, and that’s the real tragedy. I’m not a young child, and neither is my sister. We’re both adults and settled. My mother was 70-years-old. Death can come at any point; it wasn’t something I hadn’t considered.”

I was struck by Nezihe’s composure. There wasn’t a word of self-pity or bitterness in her tone as she spoke affectionately about her late mother.

“My mother had certain beliefs; she had an ideology of love. She wasn’t someone who worked with an impressive NGO, or anything of that nature. And yet, all these people who are mourning her, people whom we don’t even know, are doing so because of a personal connection they felt with her. She had the ability to connect with everyone and make them feel good about themselves. She would speak to an ambassador or a head of state in the same manner as she would speak to a maid. It’s something very few people, including myself, can do with such poise and grace. The only word I can use to describe what I’m feeling is pride.”

“I am grateful for the love and support my mother has received. Even people from opposing parties and ideologies have expressed their condolences. They had nothing negative to say about her, just as she never had anything negative to say about them in her lifetime.”

Hussain was known for bringing people together after disagreements within and outside of the party. I asked Nezihe about her mother’s relationship with politics, and more specifically, her relationship with the PTI.

“I cannot answer that question because that is something I did not understand myself. Her background was in politics, but she wasn’t a politician herself. She was not interested in party positions as such. But what I do know is that she had a faith in Imran — as a person more than a politician — which was unbreakable and optimistic, even when everyone else around her would question his character and her decision to join the party. And Mum was not wrong about people.

“The first time PTI stood in elections was in 1997; the day of the election was my father’s soyem. It was also the first time I was old enough to vote. My mother said, ‘We have to cast our votes, there’s no time to wait.’ That was the kind of person she was. Man-made rituals did not confine her because when she believed something was right, it was right.”

I was hesitant to bring up politics, keeping in mind the recent war-of-words between the MQM and PTI, but Nezihe quickly added that I didn’t need to.

“I don’t have enmities with any party because the game of politics is beyond that. That was not my mother’s ideology. She and I would often debate and discuss different political parties and their structures. She would explain that there was good work done by all of them, that all parties had some positive as well as negative aspects to them. But there was never anything negative in her statements, she never spoke ill of anyone. I never followed a political party, but I did follow her. And it is because of the ideology that she believed in, she received shahadat.”

As I left, Zahra Shahid Hussain’s sister’s words remained with me: “Our mother, who is in her 90s, used to wonder why God had kept her alive for so long.” The answer came to her only after the death of her daughter. “It is because He wanted me to be the proud mother of a shaheed daughter.” Though remarkably composed like her niece, her voice broke a little at the last sentence.

The writer is a journalist and former assistant editor at Newsline.