Jewels in the Crown

By Muneeza Shamsie | Bookmark | Published 6 years ago

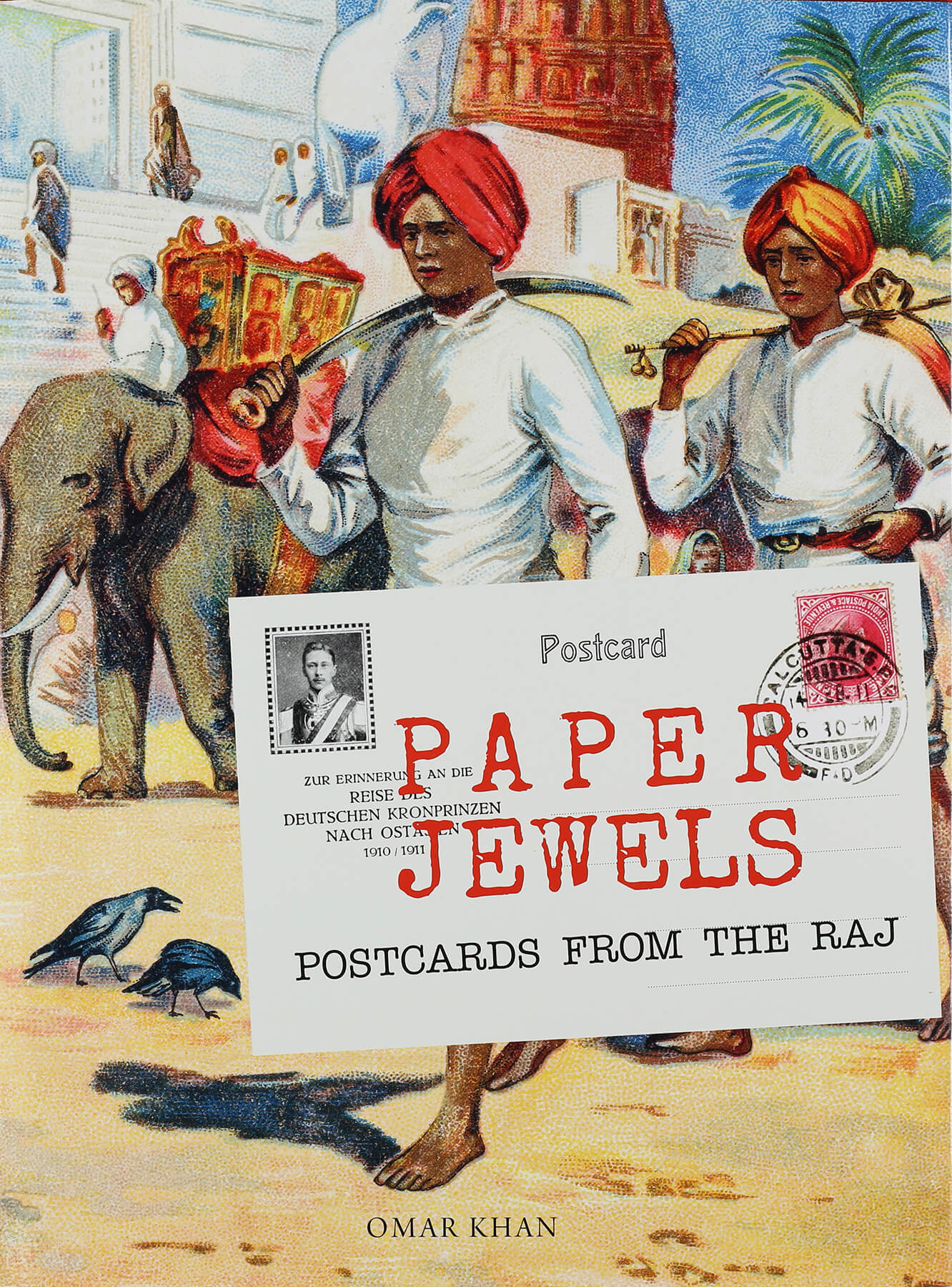

Omar Khan’s sumptuous and pioneering book, Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj, is the first to trace the fascinating story of picture postcards in the subcontinent (today’s India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka), through a rich, lively and informed text, illuminated with over 500 illustrations. Khan, a historian and web-designer, recipient of several awards for his website harrappa.com, grew up in Vienna and Islamabad, lives in California and is also the author of From Kashmir to Kabul: The Photographs of Burke and Baker 1860 –1900, an illustrated book on two photographers during the British Raj.

Omar Khan’s sumptuous and pioneering book, Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj, is the first to trace the fascinating story of picture postcards in the subcontinent (today’s India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka), through a rich, lively and informed text, illuminated with over 500 illustrations. Khan, a historian and web-designer, recipient of several awards for his website harrappa.com, grew up in Vienna and Islamabad, lives in California and is also the author of From Kashmir to Kabul: The Photographs of Burke and Baker 1860 –1900, an illustrated book on two photographers during the British Raj.

Khan’s quest for postcards and their history was impelled by the chance discovery, in California, of ‘Women Baking Bread’ postcard which dated back to 1895. The vivid, lifelike depiction of two Indian women sitting on the floor, making chapattis, reminded him of kitchens in his grandfather’s Lahore home. Khan learnt that the artist, Paul Gerhardt was probably the first to produce “artist-signed” postcards in India. He was an Austrian or German lithographer, employed by the famous Ravi Varma Press in Bombay [Mumbai]. The owner, a famous artist too, had invited Germans to join his firm and bring with them a “steam-driven lithographic press.”

This technology, together with mass-produced photographs, liberal posting regulations and the promotion of tourism by ship and rail, led to the advent of the postcard, though “the spark that proved the concept came from advertising.” The first postcards were published by Singer & Co in 1892, and came from India and Ceylon. They featured Singer employees in Parsee clothes since Singer’s South Asian agent was a Parsee. They were shown at The World Colombian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and introduced India to the United States. Other postcards advertising various products followed.

By 1895, German postcards marked ‘Gruss Aus’ (Greeting From) were used in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to advertise hotels in its German-speaking Alps and the concept spread rapidly to other places. This led to a mass production of postcards, which reduced costs and enabled tourists to keep friends and family abreast of their travels. The first ‘Greetings from India’ postcards were published in 1897 by Werner Rossler in Calcutta (Kolkata), but soon after a popular specifically Indian variation emerged: ‘Salaams from India’ by H.A. Mirza in Delhi. However, Khan maintains that “the texture of the postcard and its origins is richest in Mumbai.” He goes on to discuss some truly remarkable works in the different media they employed. He writes, in particular, of the distinguished M.V. Dhurandahr, “the greatest postcard artist of Mumbai, if not of all India” and also the first Indian to head the legendary J.J. School of Arts in Mumbai. From 1903 onwards, he created a series of lively postcards of Mumbai residents, ranging from ‘Bombay Policeman’ and ‘Parsee Ladies at the Seaside’ to ‘Marwari’ and ‘Gardener.’ Of course Khan devotes considerable space to postcards of Mumbai by other artists to include its coastline, colonial buildings and street life.

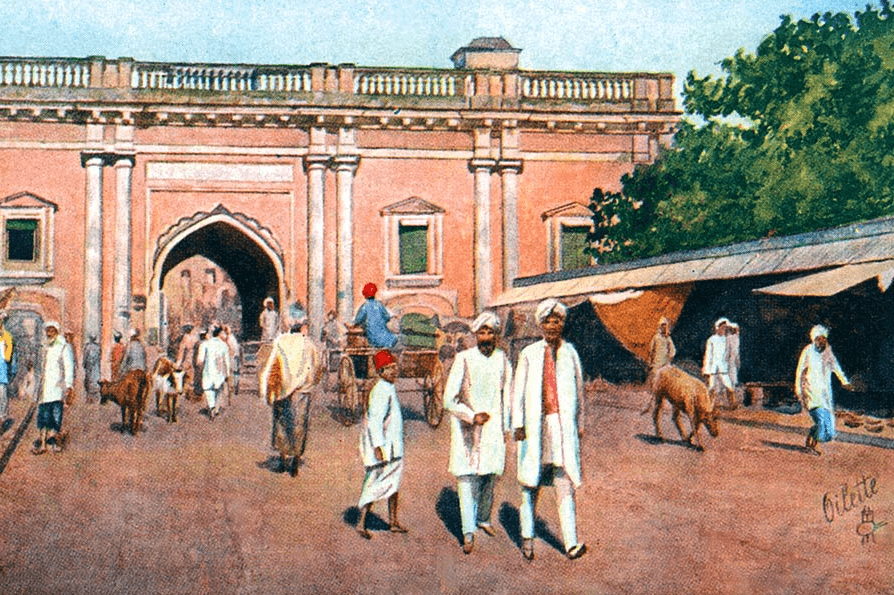

Almost all the postcards Khan discusses are reproduced in the book. A century ago, early postcards were considered works of art, to be treasured in family albums, particularly in Austria and Germany, where, between 1898 and 1903, postcard production reached billions. Postcards were also the first and only mass-scale, colour-views of that time. They were regarded as the equivalent of “what film and television are today.” In India, each significant city developed its own postcard artists, photographers and publishers.

The earliest postcards of the then-imperial capital Calcutta (Kolkata) feature lithographs of colonial buildings such as Government House; sometimes as a collage with cameo portraits of Indian exotica added – a Hindu God, or an Indian man or woman in local dress. By 1905, they extended to sketches, paintings or photographs of dancers, snake charmers, street scenes and more. On the other hand, early postcards of the erstwhile Mughal capital feature Jama Masjid, Chandni Chowk, Mughal Emperors and Mughal Queens, but they soon give way to imposing images of the 1911 Coronation Durbar and the imperial architecture of the new British capital, New Delhi.

The earliest postcards of the then-imperial capital Calcutta (Kolkata) feature lithographs of colonial buildings such as Government House; sometimes as a collage with cameo portraits of Indian exotica added – a Hindu God, or an Indian man or woman in local dress. By 1905, they extended to sketches, paintings or photographs of dancers, snake charmers, street scenes and more. On the other hand, early postcards of the erstwhile Mughal capital feature Jama Masjid, Chandni Chowk, Mughal Emperors and Mughal Queens, but they soon give way to imposing images of the 1911 Coronation Durbar and the imperial architecture of the new British capital, New Delhi.

Khan describes Lahore as “the principal city of the Punjab,” the “gateway to the northwest” and writes of its portrayal by Kipling. Lahore postcards include ‘Kim’s Gun’ and the Lahore Central Museum, founded by Lockwood Kipling. Famous landmarks such as Ranjit Singh’s tomb, the Badshahi Masjid, Huzuri Bagh, Aitchison College are all featured. Soon Lahore postcards diversify into cartoons of daily life. By 1920, Eid cards became popular too and include a stunning painting of a stately woman, sitting against cushions and awnings, driving a camel.

Khan also explores diverse and spectacular images of Benares (Varanasi), Madras (Chennai), Agra, Bangalore and Jaipur. An extensive chapter on Ceylon (Sri Lanka) captures its lush countryside, coastline, Buddhist temples, tea gardens, mendicants and performers. All of these places provide a marked contrast to postcards of verdant hill stations – Darjeeling, Murree, Simla, Ootacamund; while those of scenic, mountainous Kashmir not only include snow-clad mountains, temples and mosques, but beautiful women in richly embroidered clothes.

Through these postcards, Khan also captures the relationship of the British Raj with each of these places. His narrative is enriched by footnotes to many of the postcards stating the name of the sender and recipient, and the inscribed message. The many postcards of Karachi include Erskine Wharf, Karachi Harbour, Frere Hall, Lady Lloyd Pier, Elphinstone Street, the famous alligators at Mangophir and portraits of performers, a Karachi family and the Hindu gods, Krishna, Hanuman and Ram. There are also rich depictions of Sindh, Balochistan and the NWFP [Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] such as the excavations at Mohenjodaro, views of the Indus at Sukkur, the British Residency in Quetta, remote forts, mountain rifts, portraits of the Khan of Kalat, armed tribesmen. However, the postcards of the NWFP are those taken between the two World Wars and are “distinctive for their emphasis on conflict and uniquely disturbing subject matter,” reflecting the myths of the Empire and revealing the cruelties of the Raj. Among the most horrific is a card showing the public hanging of “rioters;” another, labelled “Frontier Loosewala or Raider,” features a decapitated man with severed limbs. But in marked contrast to these violent images and those of British soldiers, barren landscapes and a fierce ‘Mhamadan [Mohammedan] Mullah,’ there stands a colour postcard of the peaceful British Residency in Peshawar surrounded by lush vegetation.

Paper Jewels is interspersed with representations of various British kings and queens but the final chapter ‘Independence’ moves on to remarkable portraits of Indian nationalists such as Dadabhai Naaroji, Muhammad Ali, Shaukat Ali, Mahatma Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, Jawaharlal Nehru, Liaquat Ali Khan; and a rare 1930 Eid card with a photograph of Quaid-e-Azam and Miss Jinnah.

A labour of love, this is a truly exceptional book. Incidentally, its Pakistan-related postcards were recently displayed at an exhibition in Lahore, in November.