The Long Haul

By Rahimullah Yusufzai | News & Politics | Published 16 years ago

More than two weeks into the battle for South Waziristan, the armed forces have made some important gains on all three fronts leading to the Taliban strongholds of Srarogha, Kaniguram-Ladha and Makeen.

The militants put up resistance at some points but they were unable to halt the military’s advance. In fact, on occasions they fled without putting up a fight. At one place near Nawaz-kot, situated in the foothills of the mountains near the hill resort of Razmak in North Waziristan, a senior government official claimed that the militants decamped without eating the food they had just prepared for themselves. “The militants were taken unawares when our forces neared their hideout. They were preparing to eat but were so frightened that they decided to flee instead of fighting the soldiers,” Habibullah Khan, additional chief secretary at the FATA secretariat in Peshawar told Newsline.

As October came to an end, the military claimed to have killed more than 260 militants and lost around 33 soldiers in the fighting. Though there was no independent confirmation of these claims, it seems the militants have suffered more casualties compared to the troops due to the intense aerial bombing by jet fighters and gunship helicopters for the past many weeks, the shelling by long-range artillery guns and finally, the ground assault by the forces since October 17. However, the banned Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) spokesman Azam Tariq, which is not his real name, maintained that they have suffered few casualties and that the army had lost more soldiers than those conceded by the military authorities.

The three-pronged military action named ‘Rah-e-Nijat’ launched on the night of October 17-18 was aimed at encircling and defeating the militants controlling the areas inhabited by the Mehsud tribe in South Waziristan. Another objective was to deny space and safe havens to local and foreign militants carrying out terrorist attacks in Pakistani cities. The ground offensive, involving up to 30,000 troops, was preceded by bombing and shelling in a bid to ‘soften’ the militants’ positions. The military had blockaded the targeted area for months to prevent reinforcements and supplies reaching the militants and also to plug their escape routes. The blockade, however, wasn’t very effective because it didn’t hamper the militants’ capacity to fight and send suicide bombers to strike in cities in the NWFP and the Punjab.

In two weeks of fighting, the military managed to capture a number of villages including Spinkay Raghzai, Kotkai, Sherawangi, Nawaz-kot and Shelwastai as troops advanced from three sides into the heart of the Mehsud tribal territory. The fall of Kotkai — the village of the TTP head Hakimullah Mehsud and his cousin Qari Hussain, known as the “Ustad-i-Fidayeen” or mentor to the suicide bombers — and Sherawangi and Shelwastai was important for a number of reasons. Kotkai had symbolic importance as the village of the two top Taliban commanders and because it had once served as the training centre for suicide bombers. Sherawangi and Shelwastai were termed the two villages that reportedly housed a significant number of foreign fighters including Arabs linked to Al-Qaeda and members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), led by Tahir Yuldashev until his recent death in a US drone attack.

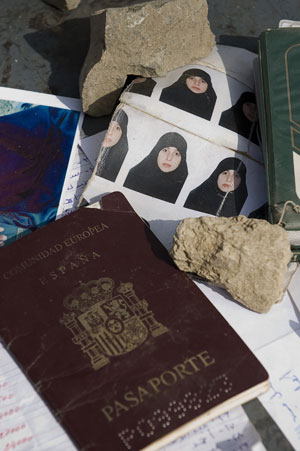

Foreign fighters: One of the foreign passports recovered belonged to Raquel Burgos Garcia, a woman from Spain who converted to Islam. Photo: AFP

The military authorities showed two passports of foreigners recovered from Shelwastai village to a group of television reporters who were flown in by helicopters to South Waziristan for a guided tour. One was of Said Bahaji, a German national accused in the past of being part of the Hamburg Cell that allegedly planned and coordinated the September 11, 2001 attacks on the US. The other passport was that of Raquel Burgos Garcia, a woman from Spain who converted to Islam and married a Moroccan national Amer Azizi, who has been accused of involvement in the Madrid train bombings in 2004. Her Spanish passport showed her wearing a scarf and Islamic dress.

Bahaji’s German passport, issued in August 2001, contained a 90-day visit visa for Pakistan. He flew to Karachi in September 2001, a week before the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington. The recovery of these passports raised the prospect that Bahaji and the Spaniard and her Moroccan husband could be in the area. Western governments, experts and the media were quick to point out this possibility. In fact, Western security analysts argued that this was evidence of a direct link between Waziristan and Al-Qaeda operatives blamed for attacks in the US and Europe. The discovery of these passports has generated excitement in Western capitals as it reinforces their belief that top Al-Qaeda leaders, including Osama bin Laden, could be hiding in Waziristan or another tribal area bordering Afghanistan. However, some analysts pointed out that members of the Al-Qaeda, Taliban and similar organisations often have more than one name, passport and identity card.

Pakistan received flak following the recovery of these passports for denying in the past that bin Laden, his deputy Dr Ayman al-Zawahiri and other top Al-Qaeda operatives were hiding in the country. The visiting US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made a blunt reference to this issue during her three-day engagements in Islamabad and Lahore by wondering aloud why the Pakistan government was unaware of the existence of the Al-Qaeda leadership on its soil and why it had failed to get them. She also put Islamabad under further pressure by stressing that it would have to take action beyond Waziristan to tackle not only militants threatening Pakistan but also the Al-Qaeda and Afghan Taliban hiding in the country, plotting and launching attacks against US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan. The US authorities were also unhappy that Pakistan has been denying the existence of the Afghan Taliban’s Quetta Shura and the presence of members of the Haqqani network in its territory. There has been no sighting of bin Laden, Zawahiri or Mullah Omar in Pakistan and the Americans have yet to provide any evidence of the Quetta Shura operating out of the Balochistan capital, but Islamabad is known to buckle under relentless pressure and concede things that it initially denies.

It was obvious from Hillary Clinton’s tone and speeches that the US considered the ongoing military action in South Waziristan, and the earlier one in Swat and Malakand, as two necessary operations that needed to be expanded further to North Waziristan and other tribal regions, and even Balochistan to take on members of the Al-Qaeda, Afghan Taliban and those Pakistani militant commanders such as Hafiz Gul Bahadur and Maulvi Nazeer who do not fight Pakistan’s security forces but send fighters across the border in to Afghanistan. This remains an unresolved issue and it could sour relations between the two countries as Pakistan struggles to contain militancy and root out home-grown Taliban and jihadis threatening the state. Its army’s assault on South Waziristan is just one battle in a war that could go on for years.

As for the battlefield situation in the rugged mountains of South Waziristan, the troops were reported to be closing in on two TTP strongholds, Srarogha and Kaniguram. Srarogha, where Baitullah Mehsud used to stay and was killed in the US drone attack on August 5, was now within the sights of the troops advancing from the Kotkai side. If Srarogha falls, the militants would have to decide whether to defend other strongholds like Makeen, Ladha and Kaniguram or escape to neighbouring North Waziristan, Orakzai Agency or other tribal areas to bide their time. Srarogha couldn’t be captured in the two previous military operations against Baitullah Mehsud as the army and the government on both occasions in February 2005 and January 2008 made peace deals with him on his terms and withdrew forces from the area. On one occasion, around 300 troops surrendered to the militants and Baitullah Mehsud’s tough conditions for the release of his men and payment of ransom had to be accepted to secure the release of the soldiers.

The troops were also poised to storm Kaniguram in the coming days. The military has been saying that Uzbek militants have converged in Kaniguram and its adjoining villages, Badar and Sam. With the fall of Kaniguram, the forces would prepare for an assault on Ladha which, along with Makeen, is another important militant stronghold. Crucial to holding the captured territory would be to occupy the peaks and higher ground in these forested valleys. Troops moving from the three different directions would apparently be manoeuvring to link up with each other at some point and secure their supply lines from Razmak, Jandola and Wana.

The military would eventually capture most of the Taliban strongholds, though it is unclear if the mission would be accomplished in the six to eight weeks estimated by the military commanders. Snowfall in winter will also determine the course of the fighting. The troops are certainly better equipped and resourced to face the cold weather compared to the militants in case they are forced out of their built-up positions and pushed towards their mountain hideouts. However, it must be borne in mind that the tribal fighters are tough and battle-hardened. Familiar with the terrain and highly motivated, they would not give up even if circumstances and the superior firepower of the military forced them to retreat and escape. Clearing the area of militants is an achievable target, but holding the captured territory and making it peaceful to facilitate the return of the thousands of displaced people and ensure the reconstruction of damaged villages and infrastructure are going to be the tougher tasks.

Pakistan’s security forces have been fighting militants since 2003-2004 and their first action in the tribal areas was in South Waziristan against the late commander Nek Mohammad’s fighters. That front was, however, in Wana area against militants belonging to the Ahmadzai Wazir tribe, who have until now been neutral in the ongoing battle in the Mehsud tribal territory. New frontlines have since been opened as the battle has expanded to other tribal areas and even to districts such as Swat, Buner, Dir and Shangla. However, it is generally agreed that the present battle in South Waziristan is going to be the hardest and longest. Its outcome is expected to determine the direction of militancy in Pakistan because defeat for the TTP in South Waziristan would certainly weaken the militants and deprive them of their most secure bases. But it will not mean the end of militancy or the annihilation of the militants as those who survive would try to find new hideouts to continue their battle.

Various figures of the militants’ strength have been given ranging from 10,000 to 17,000 or even more, but inadequate intelligence in this Taliban-controlled territory means that precise numbers or even intelligent guesses about the militants’ manpower aren’t available. The militants would be seeking reinforcements of Taliban and jihadi fighters from outside South Waziristan, but the armed forces have a greater capacity to send more troops, deploy better weapons and dominate the skies. Clearing the Mehsud tribal area of militants is a huge challenge but it can be eventually accomplished. However, holding the captured territory would be a bigger challenge in view of the likelihood of subsequent guerilla attacks by the militants and the use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) planted in the unpaved roads and on suicide bombers.

Homeless: About 200,000 people have been displaced but no camp has been set up for them due to the government’s argument that the tribespeople do not want to live in relief camps. Photo: AFP

Another challenge is to look after the needs of the people displaced by the fighting in South Waziristan and their repatriation and rehabilitation once the fighting is over. About 200,000 people have been displaced but no camp has been set up for them due to the government’s argument that the tribespeople do not want to live in relief camps. People displaced in the past from South and North Waziristan, Kurram, Orakzai, Khyber, Bajaur, Mohmand, Darra Adamkhel and other tribal areas have been complaining, with some justification, that they weren’t given the kind of support provided to the dislocated families from Swat and rest of the Malakand region.

Retaliatory attacks, including suicide bombings, are already taking place in the Pakistani cities and this might continue for some time. More than 300 people have been killed in acts of terrorism in an unprecedented spree of militant violence over the past three weeks or so in different parts of the country, particularly in Peshawar where the death toll in six bombings in the past one month has been around 200. The deadliest bomb explosion on October 28 in a crowded marketplace killed around 118 people. Spectacular raids on the army’s headquarters in Rawalpindi and police installations in Lahore, Peshawar and Kohat forced the military’s hand to expedite plans to storm militant strongholds in South Waziristan.

It is pertinent to mention that the TTP denied responsibility for the car bombing on October 28 in Meena Bazaar in the congested Peepal Mandi area. In fact, its leader Hakimullah Mehsud maintained that his group had no reason to bomb public places when it can easily target highly secure places like the Pakistan Army’s General Headquarters (GHQ) and police and intelligence agency offices. However, the general impression after every terrorist attack is that the TTP or its allied jihadi and sectarian groups, including the Punjabi Taliban, were behind these bombings. The TTP has been quick to claim responsibility for attacks on security and police forces but it goes quiet whenever public places are attacked and civilians are killed. Still, the link between terrorist attacks taking place in Afghanistan and Pakistan cannot be ruled out. After every terrorist strike in Kabul, one invariably takes place in Pakistan. With both Islamabad and New Delhi blaming each other for sponsoring acts of terrorism, it is possible that their proxy war in Afghanistan is now spilling over onto the cities and streets of the two arch subcontinent rivals.

In Pakistan itself, the military has been able to retain the support of the majority in its tough campaign against the militants. It is still enjoying substantial public backing and the media’s goodwill. As was the case before the military operation in Swat, the military leadership again received political support just a day before the attack in South Waziristan. Only the Jamaat-e-Islami and Imran Khan’s Tehrik-e-Insaf opposed this policy and both are unrepresented in the parliament after having boycotted the last general elections.

There have been allegations of extrajudicial killings by the security and law-enforcement forces in Swat and elsewhere. The heavy aerial bombing carried out by jetfighters and gunship helicopters have been causing ‘collateral damage.’ The destruction of properties of mostly innocent people and the displacement of such a large number of people is creating new problems and challenges that cannot be easily overcome. Though anti-US sentiment is still strong, there is now negligible support for the militants who were initially hailed for helping the Afghan Taliban and for challenging the American and NATO occupation of Afghanistan. Due to their ruthless actions against fellow Pakistanis and their fight against the state, the Pakistani Taliban have lost whatever little sympathy they had in the past. The common people are desperate for peace and have been offering sacrifices for the last many years in the hope that their woes were about to end. Now their hopes are pinned on the military action in South Waziristan, although it seems a military victory there may not mean the end of their miseries.

This article is related to the November cover story: The Fear Factor.

Rahimullah Yusufzai is a Peshawar-based senior journalist who covers events in the NWFP, FATA, Balochistan and Afghanistan. His work appears in the Pakistani and international media. He has also contributed chapters to books on the region.