Interview: Benjamin Gilmour

By Talib Qizilbash | Arts & Culture | Movies | People | Q & A | Published 14 years ago

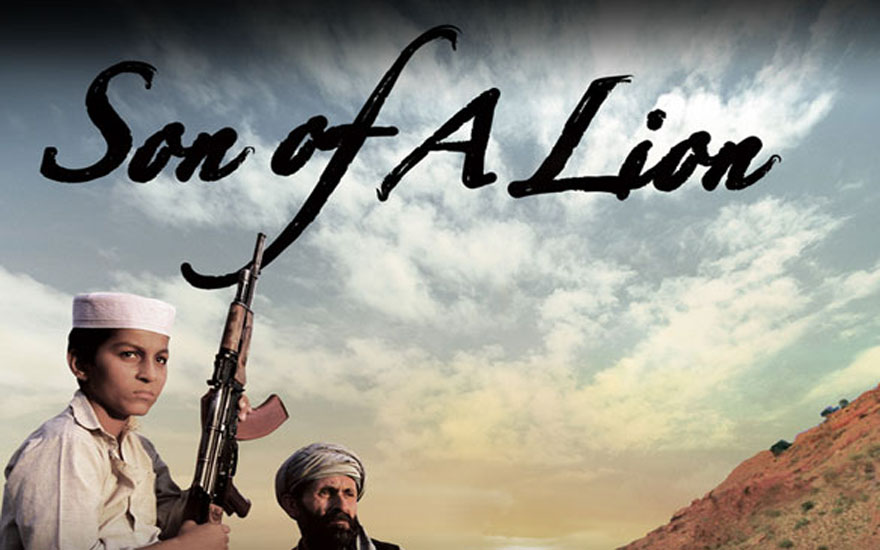

Son of a Lion opened in UK cinemas on November 6. While the story revolves around a young Pashtun boy in Pakistan’s northwest, it incorporates themes that are universal. The young boy, Niaz Afridi, is born into a weapons-making family in Darra Adam Khel, a place where family, tradition and the gun are the pillars of society. But he wants to carve his own path: instead of following in his father’s footsteps and joining the gun-making business, he wants an education. It’s something he’ll have to fight for.

The movie is being released at a time of intense international interest in Pakistan and its Pashtun-dominated tribal areas. It is unsurprising then that the setting and the story behind the making of the film are generating just as much attention as the film itself. The film’s director, Benjamin Gilmour, is an Australian who had no strong ties to the tribal areas before he decided to go in 2004. After arriving, he soon realised that his script wasn’t right. The locals told him so and made “the story their own.” But in doing so, they had to hide Benjamin and his camera from almost everybody. Newsline spoke to Gilmour after he reached London for the UK premiere of his debut feature film.

Why Pakistan and not Afghanistan for a story like this? In 2004 and 2005 the international news was all on Afghanistan and Iraq, Pakistan was still mostly on the periphery of the western media, unlike today?

Pakistan has held a great fascination for me since I first visited in 2001. It was love at first sight, I suppose. The people of Pakistan, their generosity, kindness, and hospitality is what differentiates it from most Western countries where people tend to be fixated with individualism, greed and material wealth. On my first visit to Peshawar, a man told me he kept his shop open only long enough to get enough money to feed his family that night. Then he’d close up and go spend his time with his kids. Quite simply, the values of people I met in Pakistan impressed me. As for filming there, it was precisely because the media focus was not on Pakistan that I saw the need to tell a Pakistani story. People now know how significant Pakistan’s role is, and has been, in influencing events in Afghanistan.

Who facilitated your journey? You didn’t just show up in the NWFP, did you?

Although the Pashtuns are famous for their hospitality and sheltering guests, it’s pretty impossible to just show up in the NWFP as a Westerner and expect the people to open up, given their impression of foreigners in these times. Thanks to the damage done by Predator drones and US sponsorship of the Pakistani Army, Pathans are very wary of outsiders and their true motives. So, via some references, the cousin of the brother of the son of the father of the uncle of somebody, as is often the chain of links, came through. Afridis and Shinwaris in Darra Adam Khel and the surrounding towns assisted and protected me.

Where did the character of Niaz Afridi come from?

Niaz was based on a boy I had met in Darra, the arms manufacturing township in FATA, who was working on an AK47 when I first met him in 2001. At that time tourists could easily go to Darra and pay locals for the experience of shooting machine guns into the mountainside.

I was interested in the complex issue of child labour and particularly the juxtaposition of innocence and destruction contained in the image of a child holding a gun.

Young people, no matter what culture or nationality, often have a tug-of-war with their parents about the directions of their lives, especially in choosing professions (and often spouses too). But can you talk a bit about this universal theme: is it something that you also had to personally struggle with? Did you struggle against traditionalist parents?

Not at all. I agree it is a universal story, parents putting pressure on their children, which can lead to many problems as the child reaches adulthood. But it never happened to me, at least not that I am conscious of. My parents quite simply wanted me to be happy. In saying that, many of my schoolmates have been emotionally scarred by the idea that they were never good enough for their parents. In many parts of Asia where traditional cultures are clashing with very liberal Western ways of life, we see an additional strain on the parent-youth relationship. It’s a big turning point and many Pakistani expat families in Australia, UK and Europe, as you know struggle, with this.

Was it easy to get the local Pushtuns to trust you?

No, not really. It took hundreds of cups of tea and constant interrogation as to my motives until they realised I was doing something in their interest. Once they were convinced I was out to break the Pashtun and Muslim stereotypes propagated by governments and media in the West, they were behind me 100% and Son of a Lion became their film in a sense.

Did they have their own message for the world?

Son of a Lion is their message to the world. I mean, although I came to Pakistan with a script, it was soon abandoned and we started from scratch. I gave my cast full freedom to build the story and improvise dialogue. Their message to the world is this: we are not terrorists; we are peace-loving people who desperately desire progress. But this progress has been denied them; they have been kept poor, even manipulated by forces that wish to use them as pawns in dubious agendas. As a result of this poverty and manipulation, extremism has flourished. Radical elements in their midst have given the good Pashtun majority a bad reputation, which is unfair and hardly helpful. By casting all Pashtuns in the same light we isolate the entire ethnic group. This will not help them or us. Instead, Pashtuns need to be made part of their own progress, we need to nurture them and build them. Only when the taste of progress is on their lips and hope for their children in their hearts, only then will the tribes be inclined to ward off miscreants who shelter among them.

Photo: Courtesy sonofalion.com

You said, “I gave my cast full freedom to build the story.” Can you provide some examples?

The script for the feature film I originally went to Pakistan to make was ridiculed by the locals I wanted to work with, and only then did I realise I would need to begin again, allowing the Pashtuns I was working with to take control of the story. What Britain and US and their allies are only now coming to realise in Southern Afghanistan is that Pashtuns cannot be ‘directed.’ My film making experience with them proved the same. None of them would deliver a line they were not happy with. So I gave it over to them. They built the story, with my assistance, and they improvised extensively. Many say the film feels like a documentary, even though it is acted. This effect came about no only because of the way it was shot, but because of the naturalistic way in which the actors worked.

Let’s talk about that. You have received great feedback about the natural performances of the cast. How did you cast the film?

Auditions were not possible, as they would have involved exposing our mission. So our cast was taken from a small number of families in the collaborating clans. For the most part, we got some unexpectedly brilliant performances from non-professional actors.

What about communication? How did you manage to communicate with and direct your cast?

Many of the actors were illiterate and did not speak English, so this was tough. I mean, communication is inherent to directing. What usually happened was that I work-shopped the scene with Niaz, the lead actor, who spoke excellent English. He would then, in turn, discuss the scene with the other actors in Pashto. Calling cut after an exchange of dialogue was always hit and miss as I was never sure what they were talking about, whether in fact they were giving me the exchange I wanted or just talking about the weather. Only back in Sydney after the translation was done did we see that they had, for the most part, delivered what was needed to make the story work.

You said, “Exposing our mission,” earlier. Besides the locals, the government and its agencies get quite suspicious of foreigners roaming the country, and especially in the war-torn tribal areas. What kind of opposition and encounters did you face from the government, army or intelligence agencies?

Because there is little transparency about the activities of the Pakistani government I am quite cynical about the limitations set on journalists, especially given the fact that writers and filmmakers visiting the tribal belt have to be escorted by the ISPR, the public relations wing of the army. So I never bothered applying for a permit because I knew I would be denied one. Wherever restrictions are placed on journalists anywhere in the world, I always wonder what governments have to hide. My Pashtun contacts in Waziristan and Swat suggest there is plenty.

In what conditions did you film this movie, can you talk about the time frame in which you were there and what was going on at the time?

In 2005 and 2006/7 when this film was shot, there were barely any suicide attacks anywhere. The army was only just conducting occasional operations in FATA and Musharraf was, allegedly, trying to negotiate with militants. Journalists were compared to terrorists, out to undermine Pakistan, which is an absurd idea. Of course, Musharraf’s paranoia about control escalated to his consideration of the judiciary in the same light, which was his ultimate undoing. In these conditions, the film was made in secret. I grew a large beard, stitched up camera gear in an old sackcloth and dressed in shalwar kameez. Things were getting tense and I think this film was made just in time. There is certainly no way anyone can get into FATA now.

How dangerous was filming . . . can you talk about any “close calls”?

We tried to avoid close calls, but there were a few. Once, I was on the back of a motorbike heading up to the mountain to shoot an establishing shot when we were stopped by a roadblock and they saw my camera wrapped in a chaddar. The soldier almost fired off a round from his AK47 in panic; he couldn’t believe what he had discovered. But the Afridis with me dropped some important names, some cousins and brothers in commanding army positions and the boom gate opened. The most dangerous aspect of filmmaking I think was the fact we were using live ammunition as opposed to ‘blanks’ used in Hollywood.

Any emotional scars from being in such a tough, tense environment for so long?

Absolutely. I came back from Pakistan a paranoid mess, but I have now totally recovered. When you’re looking over your shoulder and seeing villains in shadows for eight months, it takes its toll. I can only imagine how the shell-shocked Pashtuns of the NWFP feel after 700 or more of innocent tribesmen, women and children have been killed by hellfire missiles fired from un-manned drones. The psychological damage of these war crimes by the USA on the population cannot be underestimated. When I think of this, I know my experience is nothing compared to that faced by many in FATA right now.

What stereotypes did you go in with, and were any shattered through this process?

I try not to buy into stereotypes and I did not know what to expect from Pathans when I first went. In fact the film was my reaction to stereotypes of these people propagated by others in the first place. For example, in Lahore I was told over and over again to watch out for the “vicious Pashtuns.” I was told they would cut my throat and pour my blood on their rice to eat. It was absurd. Stereotyping of Pashtuns is, I found, most severe in other provinces of Pakistan, more so than in the West. It often verged on downright racism. It is weird to think that as a foreigner I may have a more accurate view of Pashtuns, their culture and their character than most Pakistanis do. But I can understand the tensions in view of the fact the largest concentration of Punjabis in the FATA right now are wearing military fatigues. This has naturally provoked a defensive response from Pashtuns living there, unfortunately adding to the misconceptions.

What is your relationship with the people you worked with like now and are you maintaining your ties?

After months living with Pathans, working on a peace-building project like this and enjoying their company and culture, life-long friendships were formed. So yes, we keep in touch.

What about showing your film to those who helped make it, the locals from Darra Adam Khel, when will they get their chance, or have they already?

Those involved in the filmmaking have seen it and I’m told some of them watch it every day. For the most part is has been widely appreciated by locals who relish in a little Pashtun nationalism at this time when they are facing unprecedented threats to their culture and way of life.

You don’t have a background in film. How did you get into this?

My background is in emergency medicine, but I think there is a clear link between this and my filmmaking. Raised with a sense of justice, when I see the underdog suffering, that’s when I react. It is my hope that this film inspires other to do the same, to find ways in which to bring humanity together, to foster understanding between people and not propagate divisions. The Pashtuns are people with feelings who desperately desire peace and well-being. If we help them achieve this goal instead of isolating them, the rest of Pakistan and the world would be very surprised by the positive outcome. Our weapons in the war against extremism and violence need to be social and economic development, health services and welfare. We need to embrace and nurture the Pashtuns and listen to their grievances. While we are killing them and making them homeless, peace will never be achieved. As a medical practitioner I have learnt over many years that healing will only ever occur if the conditions are right.

Son of a Lion is playing in cinemas across the UK. For cinemas and dates please check:

www.marapictures.com

www.sonofalion.comPhoto: Courtesy sonofalion.com