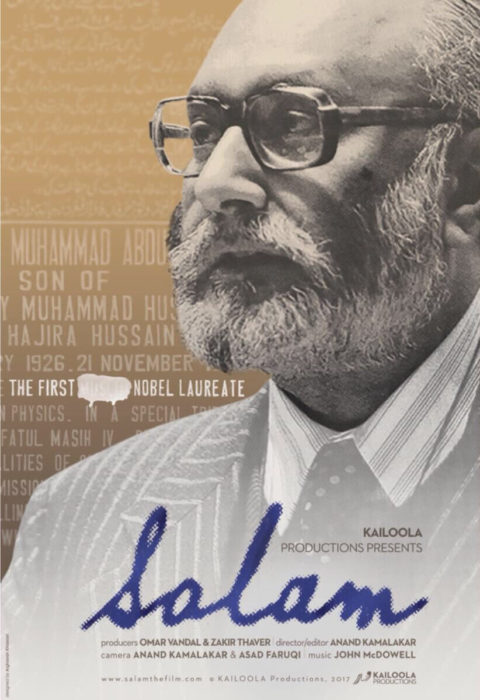

Documentary: Salam – The First ***** Nobel Laureate

By Zoha Liaquat | Documentary | Published 4 years ago

A poignant retelling of the heart-breaking story of Pakistan’s first Nobel Laureate.

I watched Salam – The First ****** Nobel Laureate over a period of three days; pausing, contemplating, crying as I learnt more about this tragic figure whose named has been wiped from Pakistan’s history. The documentary took 14 painstaking years to complete, combining rare archival footage, interviews from friends, family and colleagues and insights into the enigmatic personality of the genius that was Salam.

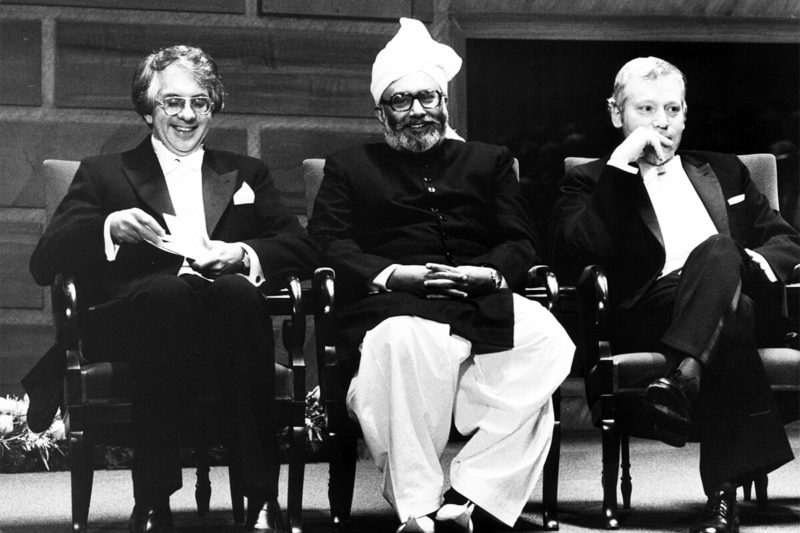

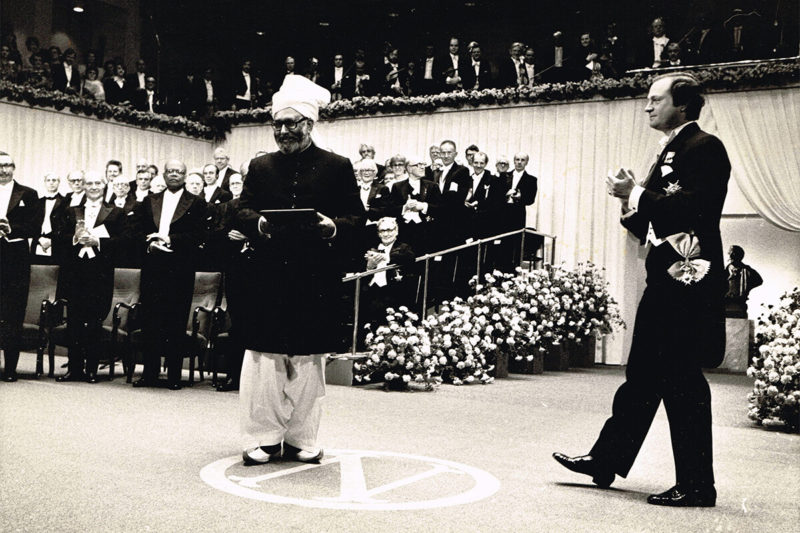

The film begins with footage of Salam, walking up to receive a Noble Prize in Physics, becoming the first Pakistani to be awarded this honour. Sadly, the Ahmadiyya sect Salam belonged to was declared non-Muslim by an Act of Parliament during Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s regime, in 1974, and so just like his tombstone, the word Muslim has been wiped clean from his identity too.

Combining interviews with his family and pictures from his childhood, the documentary details how he was the most loved of all his siblings. Ahmad, Salam’s elder son narrates how his father’s name came to his grandfather in a dream, almost as an indication that this young boy was destined for greatness. Salam was an undeniably remarkable man. At 17 he wrote his first scientific paper; at 23 he graduated from St. John’s college at Cambridge with double first class honours in mathematics and physics – a degree he completed in two years instead of the usual three; at 24 he completed a Ph.D. in theoretical physics; at 28 he became a lecturer in mathematics and Fellow of St. John’s College.

However, the documentary does not just glorify him as a hero of his times; he was every bit human, every bit irrational; a difficult boss to work for; a strict father to be raised by; a man of many moods. A former assistant details how he would resort to shouting when unable to communicate something effectively, how he would struggle with apologising for his behaviour and hand over random objects – he offered his assistant a plastic cup he picked up from the airport as a way of saying sorry. Louise Johnson, his second wife, biochemist and protein crystallographer, recounts in an interview how difficult a man he was to live with; Ahmad his elder son is seen remembering his parenting philosophy: ‘children must be seen and not heard. ’

Alongside the personal was the professional, the aspect that remained at the forefront of his life till the very end. During his speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony, Salam quoted verses from the Quran. When Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims by the state, he wrote in this diary: ‘Declared non-Muslim, can not cope.’ Fiercely patriotic, Salam stayed loyal to Pakistan throughout his life but was faced with one of the most difficult choices. When Ahmadis were declared heretics by Pakistan – the only country in the world to have a constitutional ruling on the parameters of religion – Salam said, “it became clear to me that I must either leave my country or leave physics,” and in what was a devastating loss for Pakistan, he left the country.

Salam was a tragic figure and this is a tragic documentary. As a Pakistani – and I make an assumption here about the viewer’s conscience – the only takeaway from this 75-minute long film is an overwhelming feeling of guilt, of hopelessness and of shame. Salam was ostracised by the state in 1974, but more recently in 2018, Atif Mian was asked to step down from the PM’s economic advisory council because of his faith; we are as regressive now as we were four decades ago. Religion was, is, and from the looks of it will continue to be used as a political tool in Pakistan. This is a country of Hafiz Saeed apologists, of Mumtaz Qadri supporters; this is the country that took away years of Aasia Bibi’s life on false charges of blasphemy, this is a country that has time and again stood on the wrong side of history and Salam makes it abundantly clear that this is a country that does not deserve its heroes.

A journalism graduate, Zoha's core areas of interest include human and gender rights issues, alongside which she also writes about gender representation in the media and its impact on society.