Identity Crisis

By Newsline Admin | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 17 years ago

In 1983 Salima Hashmi was among a group of artists who signed a declaration stating their concerns about the status of women in Pakistan and affirmed their commitment to cultural development on the national level through education and practice. Women artists in Pakistan have always been willing to be open and upfront about their lives, whether in actions like signing a declaration or being socially conscious in their work. They have developed ways to discuss the roles of women in the Pakistani society, even at a time when artists were discouraged from addressing socio-political concerns through art. Although there was no official policy regarding the arts in the 1980s, during the Zia-ul-Haq regime, many artists censored themselves from making volatile images that would draw attention to their work. But women, according to Salima Hashmi in an interview with this reporter in 2004, refused to pander to governmental sponsorship of Islamic calligraphy and apolitical landscape painting.

Meher Afroze was one such woman active in the 1980s, who symbolically explored her identity and her society. In the series titled Puppet, the artist considered women’s lives in an oppressive environment in which they are forced to act and conform to rigid societal standards. Her fellow artist, Nahid Raza, explored how women deal with societal pressures in Pakistan. In particular, she explored the world of a divorced, single mother in tandem with the larger struggle of Pakistani women in the 1980s. Blending the personal and the political, she reclaimed the female body in her paintings of women, from a female perspective. Women creating artwork at this time wanted to comment on the social reality that they faced; this was their way of protesting against the government. Naazish Ata-Ullah made prints that indirectly explored the military dictatorship’s decree that forced women to wear a veil. Her imagery usually included a chaddar and red spots. By initiating visual dialogues on politics, gender and society, these artists paved the way for the contemporary generation to critically examine these epistemologies.

Meher Afroze was one such woman active in the 1980s, who symbolically explored her identity and her society. In the series titled Puppet, the artist considered women’s lives in an oppressive environment in which they are forced to act and conform to rigid societal standards. Her fellow artist, Nahid Raza, explored how women deal with societal pressures in Pakistan. In particular, she explored the world of a divorced, single mother in tandem with the larger struggle of Pakistani women in the 1980s. Blending the personal and the political, she reclaimed the female body in her paintings of women, from a female perspective. Women creating artwork at this time wanted to comment on the social reality that they faced; this was their way of protesting against the government. Naazish Ata-Ullah made prints that indirectly explored the military dictatorship’s decree that forced women to wear a veil. Her imagery usually included a chaddar and red spots. By initiating visual dialogues on politics, gender and society, these artists paved the way for the contemporary generation to critically examine these epistemologies.

Today, female artists are taking bold steps in the visual arts. In fact, contemporary Pakistani women artists have outdone their predecessors in developing sophisticated and poignant works of art and have shaken the foundations of contemporary art, both here and globally. Several of them have explored issues related to their identities as women, particularly coming from an Islamic nation. Among the many others, this list includes the likes of Naiza Khan, Hamra Abbas, Aisha Khalid, Saira Wasim, Adeela Suleman, Risham Syed and Ambreen Butt.

Of these, Adeela Suleman explores conventional ideas attached to women, through the use of unconventional materials. Based in Karachi, she has been making accessories for women out of everyday domestic items since 2000. Previously, she made helmets and other safety devices that make it possible to ride a motorcycle safely, and more importantly, while maintaining a fashionable hairdo. Her current series emerged from the dangers of riding motorcycles in Pakistan by a particular economic class of women — the lower-middle class. She continues to utilise ordinary materials, such as drain covers and the painting style employed by Vespa painters in Pakistan. She now transforms women’s intimate attire into rigid constructions. The resulting colourful armour is both strong and beautiful, offering multidimensional views of the roles that women play in society. The title of one series hints at the complexity of women that is, perhaps, not acknowledged — they can be both strong and vulnerable. “Uncertainty” includes undergarments and parts of the human body made in metal. The tough forms put forth a hard exterior, while at the same time they may attempt to show that women can be delicate — intricate flowers are painted on the surfaces — without being the weaker sex.

Suleman conveys her messages by using common objects found in the kitchen. The use of domestic utensils is a methodical way to relate to women, more specifically to societal gender roles. Despite greater options for women in Pakistan, they are still expected to maintain the household and serve in traditional roles as wives and mothers, including providing meals for the family. This work does not attempt to reject these social customs because the artist accepts prevalent Pakistani attitudes, including the association of the woman and the kitchen. However, by creating over-the-top accessories with domestic items, the artist draws attention to the growing dangers in maintaining them.

Suleman conveys her messages by using common objects found in the kitchen. The use of domestic utensils is a methodical way to relate to women, more specifically to societal gender roles. Despite greater options for women in Pakistan, they are still expected to maintain the household and serve in traditional roles as wives and mothers, including providing meals for the family. This work does not attempt to reject these social customs because the artist accepts prevalent Pakistani attitudes, including the association of the woman and the kitchen. However, by creating over-the-top accessories with domestic items, the artist draws attention to the growing dangers in maintaining them.

In many of her artworks, Risham Syed also includes or references domestic material. For a young woman from an upper-class family in Pakistan today, becoming a marriageable lady means learning activities suitable for family life. Syed recalls having to take up stitching as a young girl, making baby sets for her future children. The assumption is that an eligible girl from a wealthy family will find a good suitor to marry only if she is able to cook, sew and embroider. Embroidery in her work connects to Pakistan’s colonial past because it was the British who introduced a Victorian lifestyle that included activities like embroidering for young ladies. The proper etiquette and social rules of Victorian life were adopted by elite Indians during the colonial period and continue to be practiced in contemporary Pakistan. However, Syed does not simply follow the activity as the colonisers practiced it. In some of her artwork, the artist suggests a military presence through the material she employs and a volatile environment through rendering weapons in thread. In the context of current national and international politics, depictions of guns and multinational logos seem to be appropriate. Syed took up the Victorian practice she was forced to learn and uses it to comment on Pakistani society.

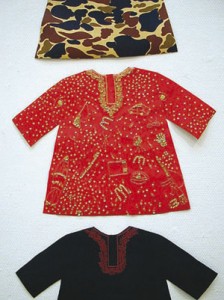

For example, Evolution Threads from 2002 includes cutouts in the shape of baby-sized kurtas. Fully aware of the dangers of growing up in this region, she produced shirts not out of the typical white muslin fabric; instead she used army camouflage printed on a rubber backing. She cut this material into a kurta shape for two of the three shirts — one with army camouflage, the other with its rubber backing. The third cutout is made with Rexene on which she embroidered missiles and a McDonald’s logo. These are contemporary signs evident around Pakistan.

For example, Evolution Threads from 2002 includes cutouts in the shape of baby-sized kurtas. Fully aware of the dangers of growing up in this region, she produced shirts not out of the typical white muslin fabric; instead she used army camouflage printed on a rubber backing. She cut this material into a kurta shape for two of the three shirts — one with army camouflage, the other with its rubber backing. The third cutout is made with Rexene on which she embroidered missiles and a McDonald’s logo. These are contemporary signs evident around Pakistan.

Harkening to the past when royal hunts were depicted in Mughal miniature paintings made in the region, Ambreen Butt shows a pursuit in which a heroic woman battles a deadly lion. By the end the animal is no longer fierce, having been defeated by a strong huntress. She is the nayika of older Indian paintings, but she does not possess the usual qualities of this heroine — typically, a woman in love seeking out her divine lover. Butt’s nayika is strong and aggressive, even though she has seductive traits. She may eventually end up with her beloved, however, the heroine in Butt’s paintings goes through struggles on her own. Like many women today, she lives her life by defining herself, and can then, perhaps, find comfort in her beloved. Along the way she experiences self-doubt and psychological pain, even as she seems determined and in control.

In one image, the woman sits on top of a settee. She poses as an odalisque, one hand on her head and the other on her hip. A miniscule lion jumps up towards her lap, begging like a dog. The nayika pays no attention to his pathetic pleas. Instead, she looks ahead into the distance in a defiant way. A second image shows her straddling the lion on the same settee. The animal is no longer tiny, yet he is no more ferocious than in the previous picture. Pinned underneath the nayika, the lion succumbs to her powerful ways.

The strength of women is made clear in the works of these three artists, even as they allow for their weaknesses to be visible. In their dualistic imagery and objects, Suleman, Syed and Butt express and examine the complicated nature of women’s identities. Their art contributes to exploring complex issues while, at the same time, it is formally experimental and brave.

No more posts to load