Much Ado About Nothing

By Zahid Hussain | News & Politics | Published 21 years ago

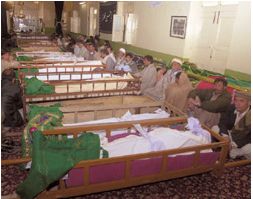

The grisly attack carried the hallmark of a well knit terrorist group. Some gunmen took up positions on the balcony of a two-storey house on Quetta’s congested Liaquat Road, while another group mingled in the procession. A huge explosion sent a massive shudder through the mourners. Hell broke loose as the armed men opened indiscriminate machine-gun fire and lobbed grenades into the procession of hundreds of mourners crammed in the narrow lane. Two suicide-bombers detonated themselves in the middle of the procession . Their bodies dangled from the balcony over the electricity wires. The carnage in Quetta on the tenth of Muharram left at least 44 people dead and scores of others wounded.

It was the third time in the past six months that Quetta has been drenched in blood by religious extremist attacks. In July last year, the city was the scene of one of the deadliest acts of sectarian violence when attackers armed with machine-guns and grenades stormed a Shia mosque killing 50 people praying inside. An earlier attack in June killed 13 police trainees from the Hazara community. It is quite evident that the administration did little to prevent the spate of violence perpetrated by the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, an outlawed extremist group. It is quite intriguing how these heavily armed terrorists continue to operate with impunity despite the government’s claims of having destroyed their network.

The latest incident in Quetta coincided with the bomb attacks on Ashura processions in the Iraqi cities of Baghdad and Karbala, which left more than 200 people dead, but there is no obvious link between the violence in Iraq and Pakistan. The Quetta bombings are indicative of the sectarian war that rages within Pakistani territory. The surge in sectarian violence and acts of terrorism raise serious questions about President Musharraf’s much-trumpeted war on religious extremism. It has been more than two years since the military leader pledged to reform Pakistani society and root out Islamic extremism. His call for an end to the jihad culture and religious obscurantism won him support at home and abroad. But his lofty promises have remained unfulfilled.

Two years down the road, the country continues to be held hostage by extremist elements. The resurgence of Islamic extremist groups is evident in the rising graph of sectarian violence, which has even hit regions like Balochistan where such attacks were previously unknown. The number of deaths in sectarian violence rose to 250 in 2002 and were more than 110 last year. Quetta, which has become a hot bed of Taliban activity, has become the main centre for religious terrorism. Instead of acknowledging the underlying cause for the climb in sectarian violence, the government as usual, has laid the blame on “external forces”.

Following the suicide attacks on a Quetta mosque last year, the government insisted that there was no sectarian conflict in the province and the attacks were an attempt by the Indian intelligence agency, RAW, to undermine the security of Pakistan. Their claim backfired when Lashkar-e-Jhangvi accepted responsibility for the attacks. A video tape sent by the group to some newspapers showed that the two suicide bombers were madrassa students. No action was taken against the madrassa the suicide bombers came from.

Most political observers do not rule out the possibility of links between the Quetta attacks and the resurgence of the Taliban. The connection becomes more probable after an investigation showed that Dawood Bindani, a close relative of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Ramzi Yousuf, was the prime suspect in last year’s attacks. Khalid, a close associate of Osama bin Laden, had reportedly spent a lot of time in Quetta before he was arrested from Rawalpindi in March last year. Ramzi Yousuf, his nephew, was arrested in Islamabad in 1993 for his alleged involvement in the 1990s Trade Center bombing plot. Their families came from Balochistan province. Bidani is still absconding, along with the other accused.

With some extremist groups operating freely, most observers had anticipated the latest Quetta attack. The government’s inaction and policy of cover-up have largely been responsible for the failure in curbing extremist violence. “The failure to deliver, to any substantial degree, on pledges to reform madrassas and contain the growth of jihadi networks, means that religious extremism in Pakistan will continue to pose a threat to domestic, regional and international security,” said a report published by the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

In his famous speech on January 12, 2002, Musharraf presented a comprehensive plan to combat Islamic extremism and terrorism. A major part of his strategy was to ban sectarian and militant organisations and to regulate and transform those madrassas whose role in promoting jihad has come under increasing international scrutiny. He also promised to ban the use of mosques and madrassas in spreading religious and sectarian hatred. “No individual, organisation or party will be allowed to break the law of the land,” he declared.

In his famous speech on January 12, 2002, Musharraf presented a comprehensive plan to combat Islamic extremism and terrorism. A major part of his strategy was to ban sectarian and militant organisations and to regulate and transform those madrassas whose role in promoting jihad has come under increasing international scrutiny. He also promised to ban the use of mosques and madrassas in spreading religious and sectarian hatred. “No individual, organisation or party will be allowed to break the law of the land,” he declared.

However, all those pledges remained largely rhetorical and seemed to have been made under international pressure. The half-hearted measures which have so far been taken, have lacked conviction. Despite the ban, most sectarian and militant groups continue working under new banners. Some of their leaders were temporarily detained, but none of them were tried in a court of law, even those against whom cases were pending. The example of Azam Tariq exposes the government’s lack of sincerity in curbing religious extremism.

While many politicians were prevented from fighting elections on patently frivolous grounds, the Sipah-i-Sahaba leader, accused of sectarian killings, was allowed to contest from jail. He was freed after he agreed to join the pro-Musharraf alliance in the National Assembly. To retain Tariq’s support the government ignored the non-bailable warrants of arrest issued against him by anti-terrorism courts. He was later killed apparently in a revenge attack by a rival group. Similarly Maulana Azhar Masood and leaders of other outlawed militant groups, were only detained for a few months under the Maintenance of Public Order, although their activities clearly violated numerous articles of the anti-terrorism laws.

Some activists of another outlawed group, Jaish-i-Mohammed, were allegedly involved in the assassination attempt on Musharraf in Rawalpindi on December 25. During the investigation it was revealed that one of the suicide bombers, Mohammed Jamil, came from a militant training camp in Azad Kashmir which had continued to operate despite strict government closure orders. The inefficiency and failure of our intelligence agencies can also be assessed by the fact that it was the Indian intelligence which had warned Musharraf of the first attempt on his life when the assassin tried to blow up a bridge over which the presidential cavalcade was passing. Indian intelligence apparently picked up the communication between the militants.

Though the government has recently cracked down on those new groups which had replaced the outlawed outfits, most political observers are doubtful whether these half-baked measures will succeed in the absence of a coherent long-term strategy. It is easy enough for the militants to operate under new banners when their leaders are moving around freely.

Despite Musharraf’s promise to reform the madrassas and eradicate extremism, the issue does not seem to be on the government’s priority list. To date no regulation has been formulated to make it mandatory for madrassas to register with the government . No national syllabus has been developed and no rules on the funding of madrassas has been adopted. Most observers agree that without any legal mechanism, or a long-term strategy in place, the government cannot prevent the flow of funds to unregulated madrassas and other religious groups involved in extremist activities.

The move to regulate thousands of madrassas appears to have stalled because of the administration’s failure to stop their funding from Pakistanis working abroad, as well as from foreign Muslim charities. The International Crisis Group report has revealed that madrassas receive more than 90 billion rupees every year through charitable donations. The amount is almost equal to the government’s annual direct income tax revenue.

Most of the madrassas, which in the past also received government funding, now rely solely on private charity. Ninety-four per cent of charitable donations made by Pakistani individuals and business corporations go to the religious institutions. Though most donors do not support the politics of religious parties, they feel that Islamic education and the preservation of Islam are the most worthy choice for their donations. The biggest source of financing for madrassas is external — from Muslim countries as well as private donors and Pakistani expatriates.

The government’s failure to curb the jihadi madrassas is largely responsible for fueling Islamic extremism. Many of the Islamic schools continue to provide recruits for jihad in Afghanistan and Kashmir. While Musharraf has repeatedly downplayed the link between jihad and the madrassas, most religious schools continue to preach jihad as an essential aspect of Islam. After the failed attempts on Musharraf’s life, the administration launched raids on some jihadi madrassas, but such half-hearted and piecemeal measures will hardly help improve the situation. “Musharraf’s failure owes less to the difficulty of implementing reforms than the military-led government’s own unwillingness,” says Samina Ahmed, director, International Crisis Group.

In order to retain international support, the Musharraf government has shown their commitment to apprehend Al Qaeda fugitives. There is, however, little evidence of it taking a tougher position against homegrown extremists, many of whom are associated with the Islamic groups that it needs for its own survival. The Musharraf government’s politics of expediency has allowed the religious right and Islamic extremists to expand their bases. And this poses the most serious threat to Pakistan’s internal security.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.