Family Politics

By Jyoti Malhotra | News & Politics | Published 20 years ago

You could call it the quiet before the storm, this eerie pre-poll silence that seems to have descended over India. Back-channel negotiations are still the order of the day, as major political parties test permutations and combinations over innumerable cups of chai and other liquids, with forgotten enemies and future friends. In these last, feverish days before the Election Commission announces a timeline for India’s most exhaustive spectacle, most likely to take place over three to four phases in April-May, the power-brokers are all over the place. Only, at least for now, they’re mostly keeping their mouths shut.

You could call it the quiet before the storm, this eerie pre-poll silence that seems to have descended over India. Back-channel negotiations are still the order of the day, as major political parties test permutations and combinations over innumerable cups of chai and other liquids, with forgotten enemies and future friends. In these last, feverish days before the Election Commission announces a timeline for India’s most exhaustive spectacle, most likely to take place over three to four phases in April-May, the power-brokers are all over the place. Only, at least for now, they’re mostly keeping their mouths shut.

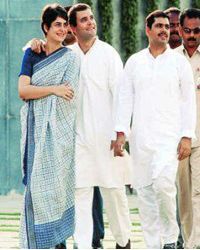

Point is, everyone knows that the election is going to be fought between the charismatic Atal Behari Vajpayee and the charming but reclusive Sonia Gandhi. What everyone’s dying to know is whether the newest Gandhi generation, Priyanka, Rahul and Feroze Varun, are going to electrify what promises to be an otherwise ponderous poll given to much electoral arithmetic, into a charged, nail-biting tamasha that is leavened with the tragi-comedy of the past-present.

As the Great Indian Elections prepare, then, to unspool for the 14th time, it’s almost clear that Priyanka and Rahul, the children of Sonia Gandhi, will not contest the fray — unlike their first cousin, Varun, who made the front pages a fortnight ago by joining the BJP along with his mother, Maneka Gandhi. On the other hand, both Priyanka and Rahul are likely to campaign for their mother as well as other Congress candidates, against the BJP. Even if Priyanka — acknowledged by many an old-timer, to have a compelling likeness to her larger-than-life grandmother, Indira Gandhi — campaigns for the Congress in the Hindi heartland of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, she may well succeed in making many a corrupted political operator in the opposition lose his or her deposit.

For proof, just ask Arun Nehru, Rajiv Gandhi’s one-time close friend and confidant, who was standing for election from Amethi on a BJP ticket during the 1998 elections and was clearly confident of winning — until Priyanka stepped in. Nehru, she thundered at street-corner speeches, was like Brutus — he had stabbed her father in the back. Unhone mere baap ke peeth mein chhura khoba hai, aap unko Amethi se kaise jeetne de sakte ho, Priyanka challenged the crowd. When the votes were counted, Nehru had come in a lowly fourth.

Similar bursts of ripened passion were on show less than a month ago as Sonia’s children once again travelled to Amethi, this time her own constituency (it had been Rajiv’s once upon a time and the family had lovingly tended to it) and sparked off a thousand rumours. As the political groundswell grew beneath her feet, Priyanka made body contact with old women in the scattered villages and questioned the locally elected member of the state assembly about unfulfilled promises. Rahul’s dimpled smile and quiet manner brought back memories of the once-naive Rajiv, but it was Priyanka who shone brightly.

Similar bursts of ripened passion were on show less than a month ago as Sonia’s children once again travelled to Amethi, this time her own constituency (it had been Rajiv’s once upon a time and the family had lovingly tended to it) and sparked off a thousand rumours. As the political groundswell grew beneath her feet, Priyanka made body contact with old women in the scattered villages and questioned the locally elected member of the state assembly about unfulfilled promises. Rahul’s dimpled smile and quiet manner brought back memories of the once-naive Rajiv, but it was Priyanka who shone brightly.

The contrast between these impassioned, young kids and the elderly Atal Behari Vajpayee, meanwhile, couldn’t be more stark. On the one hand there’s the aura of dynasty seeking to reinvent a flaccid grand old party. On the other, is an octogenarian, who’s spent all his life in the right-wing and is now coming to occupy the vast middle ground that should have ideologically belonged to the Congress. `Atal Behari Nehru’ is the latest name that has been used by the increasingly powerful Indian middle class to describe the multi-faceted Vajpayee. As the cadres of the Congress await leadership from the top, like manna from heaven, the “Congressification” of the Bhartiya Janata Party is taking place.

Whether it’s making peace with Pakistan — that could have its own unexpected bonus by calming passions across the religious divide at home — or seeking to settle the 40-year-old boundary dispute with China, whether it’s pushing the economic reform agenda in the teeth of swadeshi opposition or atoning for the Gujarat pogrom two years ago, Vajpayee’s idea of India is now publicly acknowledged to be larger and far more inclusive than that of the BJP. In the bargain he has widened the mantle, and on the eve of this election, also allowed all kinds of opportunists and event-seekers — an essential characteristic of any centrist party — to participate in the promised spoils of victory. So, Arif Mohammed Khan (better known for quitting Rajiv Gandhi’s government in 1987 in disgust against New Delhi’s refusal to be progressive over the Shah Bano case) has joined the BJP. As has Lakshman Singh, the brother of Congress leader (and until recently, the chief minister of Madhya Pradesh) Digvijay Singh. And when the press raised a hue and cry about the inclusion of a well-known gangster called D.P. Yadav into the BJP, it was PM Vajpayee and deputy PM L.K. Advani, who ordered that his four-day-old membership into the BJP be revoked.

Meanwhile, there’s Feroze Varun, the “other Gandhi,” who only the other year charmed Delhi’s middle-class literati by publishing a book of poetry. Many have claimed how he’s always been a bit of a brat, unlike Sonia’s impeccably-behaved kids, and point as confirmation to the time when he threw a major tantrum at the death anniversary ceremony of his own father, Sanjay, only last year. Now Varun’s in the BJP, just like his mother, Maneka. The irony of history is that when Sanjay, the younger of Indira Gandhi’s two sons and her favourite, died in 1980 in a plane crash, a part of Indira died with him…but that’s history. And in a nation that hardly values its history, the present is all too real.

Over the next couple of months, then, as India redeems itself, the value of dynastic politics is likely to be debated again and again. A magazine survey recently found that as many as 70 per cent of the population wanted Priyanka-Rahul to join active politics, pointing to the yawning gap in trust spawned by the BJP. As many as 41 percent (against 37 percent who said “yes”) said they were ”not” put off by the prospect of dynastic rule, and that their entry would (69 percent) dramatically help revive the Congress’ prospects.

Whatever their decision, one thing is amply clear: by this time next month, this strange silence over India is likely to be replaced by a raucous multi-lingual babble, as the world’s largest, but ever-chaotic democracy, once more, prepares to go to the polls.