Disoriented Oeuvre

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 15 years ago

Gandhara Art’s recent display Disorientation by Jamil Baloch is an exhibition that justifies its premise. By grouping disparate works into a single show, the curator succeeds in ‘disorienting’ the eye and mind of the viewer. Segmented into video, installation, relief panels and ink on paper paintings, the technically varied works emit independent readings. First impressions, seen collectively, jar the senses. On deeper engagement, a loosely centred focus evolves within the garbled narrative as strains of the artist’s recurrent concerns emerge.

A sculptor who draws and paints with equal facility, Jamil Baloch is at ease with experiment and innovation but, rather than being confined to a particular style, medium or genre, it is political and social conflicts, predominantly gender suppression and provincial discrimination, which continue to be a constant in his oeuvre. In the global context, as human suffering continues to escalate and political engagement becomes more muddied, balancing the competing factors of political rebellion and pursuit of individual ideals is becoming ever more complex for artists. In Baloch’s current show, the personal and the particular interweave, and viewers need to extract meaning from buried references to partial histories, hushed subjugation and annoying frustrations.

Most works in Disorientation critique the validity of a nation-state that is still grappling with post-independence issues. The art gains clarity when viewed through the prisms of international, national, cultural, religious, social, political, economic and historical factors, since it is the hegemony of power politics and a complexity of parallel and interacting realities that have created most of today’s catch-22 situations. Such communication must thus be read off by the receiver across layered contextual values.

Most works in Disorientation critique the validity of a nation-state that is still grappling with post-independence issues. The art gains clarity when viewed through the prisms of international, national, cultural, religious, social, political, economic and historical factors, since it is the hegemony of power politics and a complexity of parallel and interacting realities that have created most of today’s catch-22 situations. Such communication must thus be read off by the receiver across layered contextual values.

Huge enough to rivet the eye, Baloch’s six-foot cuboid installation titled ‘Sixty Years,’ constructed out of steel rods, mimics a barred cage with a ripped entrance immediately opening onto a floor stencil of bloody footprints. As confining as the cell, it emanates from the stencilled square, marked with footsteps evolving from a centre but caught in a vicious circle of limited motion. Likewise, his video installation also points to the exhaustion and futility of going around in circles but this time the protagonist is not the nation but the artist himself, laboriously charting his aesthetic journey.

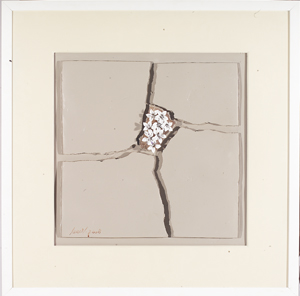

A series of fibre glass relief panels simulating the texture of parched earth in all its fissured glory, variously titled ‘Spring,’ ‘Hope,’ and ‘Deprivation,’ allude to surges of activity within a fragmented landscape. In ‘Spring’ the fractured terrain is dotted with images of fighter jets; in ‘Hope’ a hand is shown trying to creep out of a crack and in ‘Deprivation’ a fissure is plugged/smothered with a cloth. Fresh blossoms spurting out of a crevice in ‘Together’ are fetching, in spite of their life-draining bleached whiteness. The ‘Zubaan’ series, interspersed among the relief panels, is an artist’s personal indulgence with linear expressions and technical manipulations. They are more convincing as mark-making exercises than a frank dialogue on ‘Zubaan’ and the politics of language.

Today, a considerable amount of art emanating from troubled regions of the world is politically motivated and such projects on the whole have become predictable and formulaic, and one is left wondering whether engaged art looks for ‘effect’ or ‘change.’ In the Gandhara cache, a number of works thrive largely on ‘gimickry.’ For a mid-career artist with some memorable art already to his credit, catering to the prevalent and the trendy should not be on Baloch’s agenda. He should be moving towards mature expressions that do not bewilder but meaningfully challenge the imagination of his audience.

Today, a considerable amount of art emanating from troubled regions of the world is politically motivated and such projects on the whole have become predictable and formulaic, and one is left wondering whether engaged art looks for ‘effect’ or ‘change.’ In the Gandhara cache, a number of works thrive largely on ‘gimickry.’ For a mid-career artist with some memorable art already to his credit, catering to the prevalent and the trendy should not be on Baloch’s agenda. He should be moving towards mature expressions that do not bewilder but meaningfully challenge the imagination of his audience.