A Gentleman Journalist

It is becoming a rare combination these days, a journalist who is also a mild-mannered gentleman. Diehard journalist Khalid Hasan (KH), who succumbed to cancer on February 5, was of the Oscar Wilde brand — a gentleman who never insulted anyone unintentionally.

KH was generously disposed towards his peers. In his tribute to a fellow columnist, KH was unstinting in his praise:

“Majid Lahori once wrote a column called “My Column,” which he compared to a starving child who gets up every morning, parks himself in front of him and screams, ‘Uncle, I am hungry.’ I have never read a better description of what those who have to write regular columns have to face every morning. The only difference is that every time that hungry child asked to be fed, Majid Lahori produced the choicest food for him. Other toilers rarely manage to do that. And yet they go on. No doubt, column writing is a black art, and Majid Lahori was its supreme magician.”

KH, in true gentlemanly fashion, reserved the razor edge of his tongue for the most deserving. Pakistan’s UN ambassador, Abdullah Hussain Haroon was the latest beneficiary of this privileged treatment. KH’s forte was political and social satire through caricature. His “Postcard USA,” ‘Mickling away to Panipat’ is a fine example. Here’s an excerpt:

“Like a prophet from the pages of the old scriptures, our UN ambassador, Abdullah Hussain Haroon, has been sounding warnings in quarters ranging from the UN secretary general to increasingly mystified diplomats, visitors and guests, and even a bewildered European minister, that if those now knocking at the gates of Khyber are not stopped, there will be nothing to stop them from storming their way to Panipat.

“Since that old battlefield now lies in the Indian state of Haryana, I wonder if New Delhi, already reeling after the terrorist bloodbath in Mumbai, has taken note of our ambassador’s Cassandra-like words.”

“Since that old battlefield now lies in the Indian state of Haryana, I wonder if New Delhi, already reeling after the terrorist bloodbath in Mumbai, has taken note of our ambassador’s Cassandra-like words.”

Generally, though, KH’s critique was tempered with a benevolent humour. To rebuke or chastise without causing offence — in this art he was unparalleled. The one weakness KH found difficult to forgive, and witnessing which in his compatriots caused him a great deal of pain and embarrassment, was that of poor English.

Even Prime Minister Gillani was not spared:

“Although every Pakistani quotes the famous hadith about going to China in search of knowledge, in truth we learn little from the Chinese, or from anyone else. This preamble I write because of our Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani’s inability to express himself in the language he used on his just-concluded official visit to Washington. Both he and his country would have been better off had he chosen to express himself in a language he could speak with comfort.”

“He could have spoken in Urdu or Seraiki and a competent interpreter would have done the rest. Perhaps I am being generous when I say that he should have chosen Urdu because when he did address a community dinner at a local hotel on July 29, he rambled and his thoughts were disjointed and haphazard, his choice of words poor and his grammar and syntax weak.”

Of Iftikhar Chaudhry he wrote:

“I am prepared to stand in court, even his court, and assert that while in his off-the-cuff, extempore remarks, there was hardly a sentence that could be said to be mistake-free, it was painful to hear him read from the prepared text. He did not seem to realise where a sentence began or ended or where emphasis was needed and where it was not.”

“What has happened to us as a country when our prime minister is unable to understand and speak English properly and where the man who was our chief justice, and may once again occupy that high chair, is so palpably incompetent! This is not to say that his heart is not in the right place and that he did not stand up to the imperious General Musharraf, but only that he is so lacking in ability.”

Following Orwell, whose style he strove to emulate, and guided by the rules prescribed by Strunk, KH’s prose was lucid. He chose his words with care; he had an arsenal of English sayings, phrases and idioms that he delivered to effect. And he took to heart the lesson that one must show and not tell.

Following Orwell, whose style he strove to emulate, and guided by the rules prescribed by Strunk, KH’s prose was lucid. He chose his words with care; he had an arsenal of English sayings, phrases and idioms that he delivered to effect. And he took to heart the lesson that one must show and not tell.

KH’s writing sparkled with wit and humour. His incredible memory and ear for dialogue enlivened the portraits he sketched so masterfully. As press secretary to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, KH got to study him closely. He found these qualities most laudable in ZAB:

“He had humour and his timing was superb. He could read the popular mood and respond to it. No politician before Bhutto had taken the trouble to travel to the remotest corners of the country. He electrified the people who admired his daring, his courage, his turn of phrase, his youth, and, above all, his rakishness. What other politician, before or after him, could have been cheered for declaring at a jalsa in Lahore, that although he took a drop or two of ‘that stuff.’ he did not drink the blood of the people!”

Be it Noor Jehan, Qurratulain Hyder, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Ahmed Faraz, Sadequain, Z.A. Bokhari or A.H. Kardar, many of the personalities who have shaped the dreams and fortunes of Pakistan come alive in such vivid sketches. Anyone seeking a crash course in Pakistan will find it worthwhile to visit www.khalidhasan.net where KH’s columns “Private View” (The Friday Times) and “Postcard USA” (The Daily Times), along with some longer essays, are accessible.

KH looked at this world and its people with his heart. He prized kindness and extolled all who manifested this virtue. This was the highest praise he could bestow on a person. His compassion for the great humanist Sadat Hasan Manto, which led him to translate his works and share it with the English-speaking world, had much to do with Manto’s pursuit of an uncompromised life.

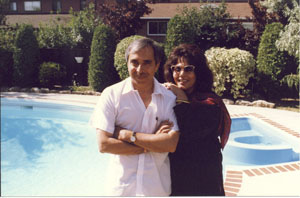

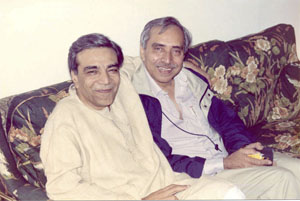

To live on one’s own terms — that was KH’s definitive measure for success in life. By his own criterion, KH was successful. Unlike Manto, who said of himself: “He hates sweetness, but will give his life to taste bitter fruit,” KH believed in le dolce vita — this sweet life. And that he tasted in plenty in the company of a vast network of talented and idiosyncratic friends and acquaintances ranging from Faraz to Noor Jehan. What is remarkable is that despite his propensity to reveal the truth about the emperor’s new clothes, KH managed to escape persecution and consequent bitterness.

On December 12, barely two weeks after 26/11 attacks on Mumbai, KH had lamented in an email:

“The Mumbai attacks have been like a nightmare. The callousness and lack of any human or even animal feeling with which the 10 attackers killed anyone who came in their way, is hard to come to terms with. I am ashamed of the fact that these young men were from Pakistan, but that is a Pakistan I do not know and with which I can never identify. I think most people would feel that way. The time has come (came years and years ago in fact) when the state of Pakistan should reclaim its lost soul and its lost writ over territories and people it pretends to govern. The world’s patience with us has run out.”

The man from Sialkot, whose romance was Lahore, melody — Noor Jehan and love — and cricket, once said: “With the exception of cigarettes, which bring no benefit of any kind to anyone, there is nothing under the sun that does not produce some good.” Along with his 41 books and his columns, KH left behind his optimism.