The People Have Spoken

By Kalpana Sharma | News & Politics | Published 21 years ago

When on Thursday, May 13, it became evident that the Congress Party and its allies were going to form the next government, most people were caught off balance. How could this have happened? No one had predicted it, not even the Congress Party.

In fact, some people in the Congress had quietly asserted that they would win. And the person who first went public with this prediction was none other than India’s new Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh. At a press conference in Mumbai in April, Dr. Singh said, “Our understanding is that the country is heading for a change of government at the centre. I am confident that the Congress with its allies will get a workable majority and will be able to form a government.”

This statement was made in such hushed tones that the press almost missed it. Yet, on hindsight one can see that people like Dr. Singh and the Congress Party could hear what the media and the pollsters could not — the growing disillusionment with a government and a party that saw only a shining India and missed the growing dark spots.

As a matter of fact, people expressed their anger and disillusionment each time they were asked. The electronic media had reporters and cameras all over the countryside. And one word that was shouted out by men and women, in villages and cities, was ‘Water.’ How could India be shining, they asked, if you did not have water to drink or to water your fields, if your crops were dying and your children suffering from disease? Everyone heard these voices, but no one listened, least of all the members of the then ruling alliance, the National Democratic Alliance led by the Bharatiya Janata Party.

When Muslims were asked who they supported, they were often sullen, silent, but they were clear about who they would not support. Could any Muslim vote for the BJP after what happened in Gujarat? From Kerala to Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat was a live issue in the mind of every Muslim voter.

‘Give Us Jobs,’ was the other cry often heard. Factories are closing down, said laid-off workers in India’s industrial heartland. Where is this shining India, they asked? Once again, no one listened carefully enough. No one calculated how such sentiments would translate into votes.

‘Give Us Jobs,’ was the other cry often heard. Factories are closing down, said laid-off workers in India’s industrial heartland. Where is this shining India, they asked? Once again, no one listened carefully enough. No one calculated how such sentiments would translate into votes.

On May 13, all this became clear. Muslims voted tactically. They decided to support the candidate best equipped to defeat the BJP or its allies. In constituency after constituency, such voting made the crucial difference. Instead of dividing the votes of the anti-BJP parties, it helped consolidate it. In a city like Mumbai, for instance, where Muslims comprise 12 per cent of the population, this kind of tactical voting ensured that out of six seats, the Congress won five. In the last election, exactly the opposite had happened.

And for the rest, people not affected by the BJP’s anti-minority politics, issues of governance decided their choice. If after five years, a government that boasted of making India an economic super power could not provide potable drinking water to its people, then clearly something was amiss. You did not need to be a PhD in development economics to work that out.

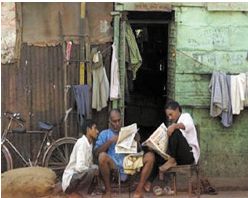

The most encouraging aspect of this election, as with previous elections, is the increasing confidence with which millions of poor people in India are now using their vote. The middle class continues to be apathetic. But the poor have now understood the power of the secret ballot. And they are using it effectively both at the state government level and in general elections.

The most convincing proof of this is the regularity with which pollsters go wrong. They can dish out any type of scientific formula to work out a representative sample and extrapolate a likely result. But they are always wrong. And usually spectacularly wrong!

This time, they claimed that an election spread over more than a month would allow them time to conduct accurate exit polls. But once again they were wrong. They assumed people would tell them truthfully for whom they voted. They forgot that people prefer to keep their choice to themselves. After all, it is a secret ballot. And the Indian voter has understood the power of that secret vote. So why should they reveal their hand to a person waiting outside a polling booth? This can be the only explanation for the wide discrepancy between the predictions and the actual results.

And finally the BJP’s hearing disability, so to speak, was the consequence of the arrogance of being in power. They heard only what they wanted to hear. The media fell for the hype and kept repeating their words. In the ensuing cacophony, the quiet voices of ordinary people, their cries of distress, their hopes for a change, were drowned out.

But not permanently. Because the real story of the Indian election is that regardless of what the media says, over and above the bombast of the politicians, lies the quiet determination of ordinary people. If they decide they want a change, they now know how to bring it about.