Ring Out The Old

By Zaffar Junejo | Heritage | Published 12 years ago

Come Divali, the festival of lights, and the houses in Thar come alive with colourful paintings of peacocks, chukars, horses and camels.

Come Divali, the festival of lights, and the houses in Thar come alive with colourful paintings of peacocks, chukars, horses and camels.

This art form, which is to be found in the deep southern part of Pakistan, is commonly known as Rajasthani Art. But a few also refer to it as Adivasi art, indicating its connection with the indigenous tribes who live in the Thar Desert. And the art is found in abundance in the villages bordering India.

Painting homes with decorative birds and animals is a quintessential part of a Thari villager’s life and this activity is undertaken at the time of a wedding in the family, or to welcome the arrival of a new season or to celebrate a religious festival.

The practitioners of this art are young women who belong to the scheduled caste. All of them live around the neighbouring towns of Nagarparker and Chachhro. Newsline met with Dhani, one of the artists of Bodesar village, which is situated at the foot of the Karonjhar Hills. She shared that she, like the female artists of Adhigam village, had learned the craft from her mother and grandmother. But times have changed. According to Chandra who lives in Adhigam, the Gujrati-language TV channels from across the border have assumed the role of the new art teacher.

The designs and the use of colours in popular Indian soaps and family dramas are being copied. In fact, women like Chandra consider themselves lucky that they have access to newer designs and colours through their solar-powered TV sets. But Revathy, who lives in Kasbo village, argues that while it is true that in the olden days there were just one or two designs — featuring a flower or a bird — there was a wide choice of colours. And while she agrees that the shades of colours seen in TV shows are relatively new, one needs extra money to buy them. Moreover, these unusual colours are generally not found in the local bazaars, and the nearest place where they might be available is Mirpurkhas, a market town far away from Nagarparkar or Mithi.

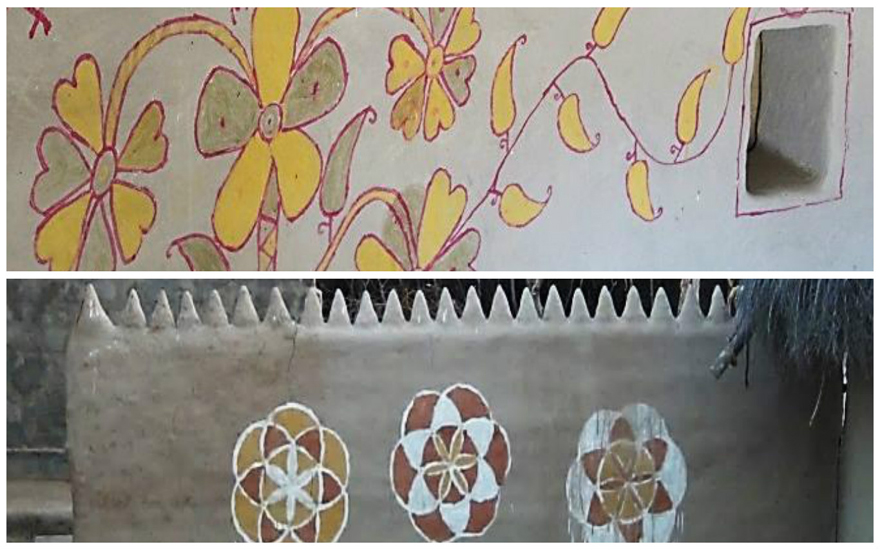

Members of the older generation, who harbour nostalgic memories of undivided India, recall that the interior and exterior walls of their homes were plastered with a thick solution of red or white clay. The clay was brought in from the site of newly constructed wells. This layer served as the base. A local female artist, who usually hailed from the same community, would be requested to draw on it, using patterns that she had learnt from her mother or grandmother. In most cases, they included images of flowers, peacocks and quails. Some basic geometrical shapes were drawn repeatedly throughout the length of the rectangular walls. To these repetitive patterns were added blooming flowers and leaves. Afterwards, these drawings were filled in with locally produced organic colours. The most frequently used colours were red, green and blue, that were made by the artists themselves. These were extracted from the leaves of plants like babul, neem, kandi and ak and then processed.

Surprisingly, the households are not consulted or informed in advance about the patterns or drawings that the artist plans to make. Once a family member has specified the spots which have to be adorned with Adivasi art — the exterior walls, open space kitchens, entrances and the area where utensils are kept or washed are normally chosen — the artist gets to work, without any interference from the residents. It is only after the artwork is complete, that the residents take over and embellish the paintings by affixing gold-coloured shells of beetles, which are collected in the monsoon season. Some women also paste shiny sheets of paper — usually the foils used in packing tea leaves — on the surface, which serve as reflectors, along with tiny glass mirrors. The mirrors are taken from discarded traditional dresses of the women.

The network of cellular phones and TV channels, along with newly constructed roads, has brought a revolutionary change in the perceptions and lifestyles of the desert dwellers. A majority of them now aspire to have a pucca house instead of a katcha one. Hence, the refined clay which was earlier used to plaster the walls has been replaced by a thin layer of cement. This change has triggered a new art wave: Free-hand drawings have now been replaced by symmetrical designs, and organic colours can no longer be used on the cemented texture of newly constructed houses. This change poses a fresh challenge to the female artists. None of them have any hands-on experience of working with cement, sand and baked bricks. A new style of construction, the use of synthetic colours and the standardisation of designs have forced women artists to quit this creative form of expression.

It is obvious that the altered situation favours men, irrespective of whether they are artists or not. Initially, they start their careers as masons and later on develop the expertise required to build their careers as home decorators. In fact, most of them learnt their craft while they were working as masons during the construction boom in Hyderabad and Karachi. These masons-cum-artists use two techniques to carve out the drawings on the cemented layer. One is a tracing technique — a thin paper is punctured with small holes, and then powder of any colour is puffed to get the imprint of the design on the wall. But experienced masons employ another method — that of folding paper into a triangular shape and then using the tracing technique to transfer the geometrical designs onto the surface. It is a tricky exercise and needs to be handled with care.

Thari masons-cum-artists avoid drawing pictures of religious symbols and replicas of plants and animals. They prefer to draw geometrical patterns, which are relatively easy whereas drawing fauna and flora requires artistic skills. However, it is commendable that despite the odds, women are still drawing images of Lord Rama, Sita and the joyful Krishna.

Thari masons-cum-artists avoid drawing pictures of religious symbols and replicas of plants and animals. They prefer to draw geometrical patterns, which are relatively easy whereas drawing fauna and flora requires artistic skills. However, it is commendable that despite the odds, women are still drawing images of Lord Rama, Sita and the joyful Krishna. And additionally, they are keeping alive the art and culture of the Thar desert, which their grandmothers and great grandmothers have nurtured over the centuries. Incidentally, none of the women artists accept or ask for any remuneration in cash or kind. For them, their art is an act of worship — sacred and divine.

Thari masons-cum-artists avoid drawing pictures of religious symbols and replicas of plants and animals. They prefer to draw geometrical patterns, which are relatively easy whereas drawing fauna and flora requires artistic skills. However, it is commendable that despite the odds, women are still drawing images of Lord Rama, Sita and the joyful Krishna. And additionally, they are keeping alive the art and culture of the Thar desert, which their grandmothers and great grandmothers have nurtured over the centuries. Incidentally, none of the women artists accept or ask for any remuneration in cash or kind. For them, their art is an act of worship — sacred and divine.