“In the post-Cold War period, the US has constantly won wars and lost the peace”

By Newsline Admin | Cover Story | Published 12 years ago

Is there any truth to the commonly held perception that Pakistan has a love-hate relationship with the US?

The US-Pakistan relationship cannot be described as a love-hate relationship. The opinion polls in both countries regarding each other are too low for such a description. The nature of the relationship is too shallow for words such as “love” and “hate” to apply. The negatives, moreover, far outweigh the positives in mutual perceptions for hyphenated opposites to characterise the relationship.

US-Pakistan ties are much better described as a roller-coaster relationship reflecting power asymmetry, different sets and ranges of interests, elite convergences, contingencies, conflicting expectations, deception (including self-deception), etc. It remains a substantive but deficit-ridden relationship that is limited by the arrogance and ignorance of policy-making in the US, and the self-serving perversity of policy-making in Pakistan.

What have been the major irritants in this relationship?

There are a number of irritants. From the US perspective, they currently and primarily include the allegedly “frenemy” (friend/enemy) policies pursued by the Pakistan government towards US interests in Afghanistan. This includes jihadi safe havens and infrastructure in Pakistan which enables a jihad to be waged against US-led occupation forces in Afghanistan. Insurgencies that have safe havens, sanctuaries and support systems beyond their country’s borders are seldom defeated.

The US believes its strategic objectives in Afghanistan have been thwarted by a powerful, anti-US and pro-Islamist “establishment” in Pakistan that wishes to preserve its “influence” in Afghanistan and counter Indian interests there.

Conversely, the Pakistan government is irritated by drone attacks and by the US media and Wikileaks revelations that it was itself largely complicit in these attacks against its own people.

Many in Pakistan see US kinetic policies in Afghanistan as having exacerbated the refugee and terrorism problems it faces. US policies have, as a result, played a large role in reducing the writ of the government over large swathes of its own territory. The unreliability and allegedly modest amount of US assistance compared with the costs of compliance is also referred to. Finally, there is the perception that while Pakistan has been playing a domestically unpopular role of sidekick and watchdog for US interests in Afghanistan, the US sees India, and not Pakistan, as its strategic partner of choice in the region. A raw deal indeed!

What were the challenges you faced in your tenure?

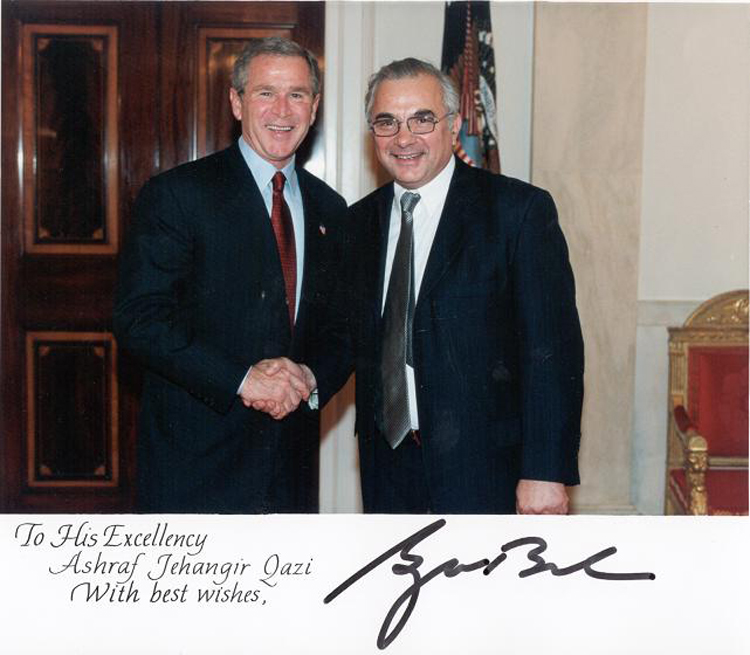

I was in the US from 2002 to 2004. This was just after the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington. The US was traumatised, vengeful and arrogant. Musharraf had already submitted to its demands. The Pakistani community in the US had to face the consequences of American hysteria. Several workers were arrested and deported, often in humiliating circumstances, as a result of minor infractions of the law — despite the well-known reputation of the community for being law-abiding, peaceful and hard-working. With the help of a number of admirable young Pakistani-American lawyers, the embassy was able to make a difference in a difficult situation. Musharraf’s volté face was appreciated by the American establishment. But many were suspicious that his heart was not really in the job of being America’s enforcer in his own country despite the fact that he, and Pakistani leaders before him, were happy to violate Pakistani legal due process and constitutional protections to hand over “high value targets,” including Pakistani citizens, to the US for “processing.” American munificence, in the form of military and economic aid, was always encumbered by conditions and procedures that severely compromised its stated value.

Both Musharraf and Vajpayee visited the US while I was there. The Musharraf visit went off well enough, but it also defined the relationship as circumscribed and provisional. The Vajpayee visit revealed policy differences and reservations on both sides, many of which pertained to Indian concerns regarding alleged US “indulgence” towards Pakistan. But it also highlighted a degree of strategic convergence and shared interests and values that have yet to inform the Pak-US relationship.

It is generally believed that:

a) The Republicans are more supportive of Pakistan than the Democrats.

b) All US governments are more comfortable working with military governments in Pakistan (Generals Ayub, Zia and Musharraf).

Do you agree?

The Pakistani leadership has traditionally been more socially conservative than that of India. The BJP interlude was, to some extent, an exception. The Republican Party in the US has similarly been relatively more socially conservative than the Democratic Party. One was the party of ‘business’ while the other was supposed to be the party of ‘labour.’ Today, both are parties of ‘corporate America’ and have a more or less undifferentiated policy towards Pakistan.

But in Pakistan the impression of Republican partiality towards Pakistan is still rife, particularly in the military.

As for the apparent US comfort levels with military governments in Pakistan, this is due more to their better ability to deliver on US demands than civilian governments, about which it is never clear how far they are really in charge of security and other policies of particular interest to the US. The military in Pakistan is often seen to be a nuisance by the US, but a manageable nuisance. The civilian governments and, more particularly, the ruling political parties are seen as, by and large, unable to manage themselves, let alone deliver on anything.

In the context of the war on terror in Pakistan, the US has continued to ask Pakistan to do more and more. Is there any understanding or realisation of what Pakistan itself has suffered in the war on terror?

Anyone familiar with US foreign policy should know it has never been particularly concerned with international law or the costs it imposes on countries run by compliant governments. Whatever the precise estimates of costs for conniving in the US war on terror in Afghanistan, the costs to Pakistani society are plain for all to see.

We may similarly ask: What about the unspeakable suffering of the people of Iraq, Libya, Occupied Palestine, etc.? What about the still accumulating costs of US policies decades ago in Vietnam? What will be the legacies of US policies in Afghanistan and Pakistan which are taking shape before our eyes today? Do the Americans really care? I believe they would if they knew what was actually happening. But mainstream US media — and to a depressing extent, even US academia — have sought to ensure that they never will. There is, of course, admirable resistance to this state of affairs inside the US. But it has a long way to go. Under the circumstances, the more appropriate question would be whether our own governments care about the debilitating costs of their own compliance with US demands.

This government, as also previous ones, have talked of trade, not aid, with the US. Given the situation in Pakistan, do you think this is a realistic demand?

It is a realistic demand provided we make realistic economic policies and implement them. Today, South Carolina has a veto on Pakistani textile exports to the US. But this is only because Pakistan has failed to develop any countervailing economic or strategic power over decades. The economic, and therefore political, benefits for a US Administration in upsetting domestic cotton textile interests in order to curry favour with Pakistan are not apparent.

All this can change if Pakistan enlarges its market and diversifies its economy so as to become an attractive place for US business and investment. As long as Pakistan depends on the US Administration to press its case for its exports nothing much will happen.

In his book Shooting for a Century, Stephen Cohen maintains that the US policy apparatus for South Asia, has been severely deficient and dysfunctional. Do you agree? Also that the US policy of dehyphenation in the context of India and Pakistan has worked in India’s favour. Should Pakistan be feeling insecure about the US’s growing links with India?

Cohen, as an American, articulates American policy interests. Those have not been achieved in Pakistan largely due to policy inconsistencies and its short-term policy framework. US foreign policy is often tied very closely to the American domestic political calendar which doesn’t make for consistent and sustained policy commitments. That is why in the post-Cold War period, the US has consistently won wars and lost the peace. American intangible and soft power is waning and this, sooner or later, impacts on the effectiveness of its hard power.

India refused to be hyphenated with Pakistan and Afghanistan. The US complied. Pakistan could do nothing about its demotion to the Afghan league. If Pakistan can get its act together it should have nothing to fear from the US-India or the Afghan-India relationship. It fumes and frets only because it cannot get its act together.

Do you see the US using its good offices to push for a Kashmir solution, despite Indian resistance?

The formal position of the US Administration that Kashmir is disputed territory remains unchanged. But since long, and largely as a result of several gratuitous policy blunders by Pakistan, the position of the US and most other countries has shifted from an implementation of the UN resolutions on Kashmir to a solution of the issue through bilateral dialogue between the two countries in accordance with the Simla Agreement. The US is quite open to the suggestion of using its good offices to encourage such bilateral dialogue, but not to broker a solution, which India would never countenance. India as the status quo power in Kashmir welcomes the US attitude. Pakistan as the “revisionist” power remains unsatisfied because it has neither the military nor the diplomatic leverage to force a solution that would be an improvement on the status quo.

At present, the US sees it as foolhardy to venture into such a quagmire unless Pakistan can develop credibility and options. Can the prime minister credibly articulate a vision and a strategy for Pakistan, and Pakistan-India relations, in which to situate and implement his Kashmir policy consistent with existing UN resolutions?

In your view, does the US administration see Pakistan as a help or hindrance on the road to peace in Afghanistan?

In your view, does the US administration see Pakistan as a help or hindrance on the road to peace in Afghanistan?

Both. The US Administration sees the Pakistan government as double-faced and unreliable. In turn, the Pakistan government sees the US Administration as selfish, short-sighted and frustrated. There is little mutual trust, but both need each other.

The road to peace in Afghanistan is a multi-tiered process involving the Afghan parties among themselves, the regional countries pledging to support that process and eschew interference, and the larger international community making good on its pledges to shore up the Afghan economy despite the global economic situation.

Do US regional policies support the prospect for such a process developing? Do India-Pakistan relations contribute positively towards it? Does the government of Pakistan have any credible thinking on the subject? But just as there are vicious circles, there can be virtuous circles. Get something good and significant started and its interactive knock-on effects could impact the situation in significantly positive ways. Once again the issues of vision, leadership and commitment are paramount for anything to happen. Pakistan is indeed a key player. But a player who can unlock nothing will carry no weight, except as a spoiler. Both the US Administration and the Pakistan governments have been hindrances to an Afghan settlement.

The Americans will be leaving Afghanistan next year. Do you fear, as most Pakistanis do, that Pakistan will suffer the same fate, or worse, than it did post-1989, following the end of the Cold War?

It is far from clear that US combat forces are really leaving by the end of 2014, given the US rejection of a “zero option,” the security agreements it is negotiating and the nine military bases it reportedly insists on retaining.

Should all US combat forces actually leave Afghanistan, pent up administration and Congressional frustrations with Pakistan may inform new anti-Pakistan legislation and measures, as the US withdrawal process is completed and its need for Pakistani cooperation declines. The impact on Pakistan’s economic revival and political stability could be calamitous.

Will Pakistan always be policing for the US, given its frontline status?

This is tantamount to asking whether Pakistan will remain a mercenary power. It has essentially done so for over six decades, without much benefit to itself or earning the sustained appreciation of its masters.

If significant movement towards good governance and all that national transformation entails is made, there will be no need to be the underpaid cop of the US. But as of now this seems to lie beyond our political imagination.

Does Pakistan have any friends on Capitol Hill?

Friends, we have. Effective friends, very few, because of our own policies as well as the nature of the dominant perceptions and policies within the current spectrum of US politics. Lobbies have become rackets because of the way our leaders have supplanted national priorities with their personal priorities. A Chinese diplomat was once asked which US firm he had hired as a lobbyist. He answered, only half in jest, that he had hired the whole corporate sector of the US which sought to sell or invest in China.

Which areas do Pakistan and the US need to particularly work in to develop a measure of trust?

If the Pakistan government earns the trust of its own people, it will sooner or later compel foreign countries to respect its policies and concerns. In the case of the US, there is a complication. Should Pakistan achieve a measure of real policy independence by being able to prioritise its people’s interests over US strategic requirements, US trust is likely to move in an inverse relationship with the growing trust of the Pakistani people. This is a challenge that needs to be recognised.

There are the well known concerns of both sides. The US stated concerns pertain to Afghanistan, terrorism, dialogue and peace with India and the strengthening of democracy. Pakistan is concerned about energy, economic revival, education and the eradication of extremism — all the Es! Despite the severe challenges in US-Pakistan relations, mistrust can be minimised to a considerable extent by Pakistan through pragmatic policies that eschew provocation and confrontation towards the US and build cooperation and influence with all its neighbours, including India, despite serious differences on Kashmir. If it can rationalise its policies towards Afghanistan, despite perceived provocations from Kabul, it can develop a welcome influence on behalf of promoting a stable and lasting peace settlement. The adoption of such policies will entail overcoming domestic pathological forces that have accumulated power and influence over recent decades because of policies based on an institutionalised, sustained and deliberate perversion of ideology. The risks and costs of trying to do so will be very high, and if our leadership continues to be risk averse no matter what happens to the country then we will have no answer to the existential challenges our country faces today — at least not within the current political dispensation.

Ostensibly Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif failed to secure any concessions, any promises from the US President on his trip to the US: drones, Kashmir, Afia Siddiqi. Both agreed to disagree. Would that be a correct assessment?

These expectations were never realistic. What matters is the impression the prime minister made on Obama and the US administration, as well as in his meeting with the House Foreign Relations Committee and other forums. Given that he has yet to make a strong impression in his own country it is unlikely that he made too much of an impact abroad. But he is entitled to more time in which to stamp his authority on policies.

If the Pakistan government makes any headway in its talks with the Taliban, do you see the Americans halting the drone attacks?

It would contribute towards the possibility that Pakistan’s arguments against drone attacks would be taken more seriously in Washington than they have been up until now.

One of the sticking points in Pak-US relations is the role of the ISI, specially the alleged support of the Haqqani network. How does a civilian government address this issue?

The ISI is a military organization even though it formally reports to the Prime Minister. Its real boss has always been the COAS and sometimes it exercises a considerable degree of independence from him also. There has never been any proper civilian supervision or control over the ISI. With each domestic political and security crisis, including East Pakistan and Balochistan, it has expanded its power, its role and its immunity to accountability i.e. impunity. Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari each sought to assert control over it. All of them failed. The ISI has insisted on a key role in Pakistan’s India and Afghanistan policy, particularly as far as handling Jihadi groups is concerned. This includes the Haqqani network which former US Chief Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mullen, described as “an arm of the ISI.” The ISI, of course, has its own answer to these allegations. Can Nawaz Sharif assert policy control over the ISI which supposedly reports to him? Does he even want to, given what happened to him the last time he took on the military? This is just one of numerous challenges he confronts and which he will have to overcome before he can even begin to deliver on his promises to the electorate and be taken seriously by foreign and domestic interlocutors.

Was there ever a golden period in Pak-US relations?

During Ayub’s time, we were supposed to be the US’s “most allied ally” and we received very significant military and economic assistance. That was as close to a golden era as we ever got in our relations with the US. But they were fatally flawed because of the conflict of assumptions and expectations on which they were based.

No more posts to load