Everyman’s Last Breath

By Ali Bhutto | Metropolis | Published 7 years ago

Atif Safdar, son of Safdar Mehdi and the current owner of Everyman Book House. (Photos by the writer).

Everyman Book House is a reflection of Karachi’s dying soul. Born on a footpath of the city in the 1950s, it is the baby of Safdar Mehdi, who arrived in Karachi from Allahabad, India, in 1951. His was one of many nameless stalls – what Mehdi’s son, Atif Safdar, refers to as “cabins” – that dotted Regal Chowk in those days.

Today, the shop is located in an office block in Saddar and run by Safdar, who inherited his father’s only fortune. But the prized collection of antique and rare books is not what it used to be. Safdar feels a sense of duty and emotional attachment towards the collection, but he is not as passionate about it as his father. Karachiites on the whole seem to be less interested in books, according to him. “In my father’s time, we had about 150 regular customers,” he says. “Today, I have only 15.”

In the last eight years alone, the shop has witnessed a considerable decline. When I visited it in 2010, Everyman was housed in the adjacent Fareed Chambers and exuded an understated, old school charm. In the dark, paan spit-lined concrete corridors of Saddar, it was an oasis of books, one of Karachi’s forgotten gems. In the quaint, dusty rooms, some volumes were organised vertically due to a lack of space. Antique and rare books graced the shelves. Safdar, too, was more enthusiastic back then. He came across as a man custom-made for the role of a bookseller – not unlike those eccentric salespersons in offbeat comicbook shops in the West that also sell collectibles. It was a book-lovers’ paradise and the kind of place where, if you spent enough time probing the piles, you would discover some unexpected secrets. It was a tiny space caught in a storm of books.

Today, the shop looks like it has been hit by a tropical storm. There is no longer any method to the madness. Half the shelves are empty and mounds of books litter the floor as if they were thrown there in a fit of rage. In fact, they lie in the exact spot in which they had been dumped when Safdar shifted to the new location, six months ago. Since he is the only one looking after the shop, he hasn’t had the time to organise the volumes on shelves. The books that did make it to the shelves, however, remain in the shadows, reluctant to reveal themselves. Located in one of the back chambers of an office block, the space is devoid of sunlight. A sense of gloom hangs in the air.

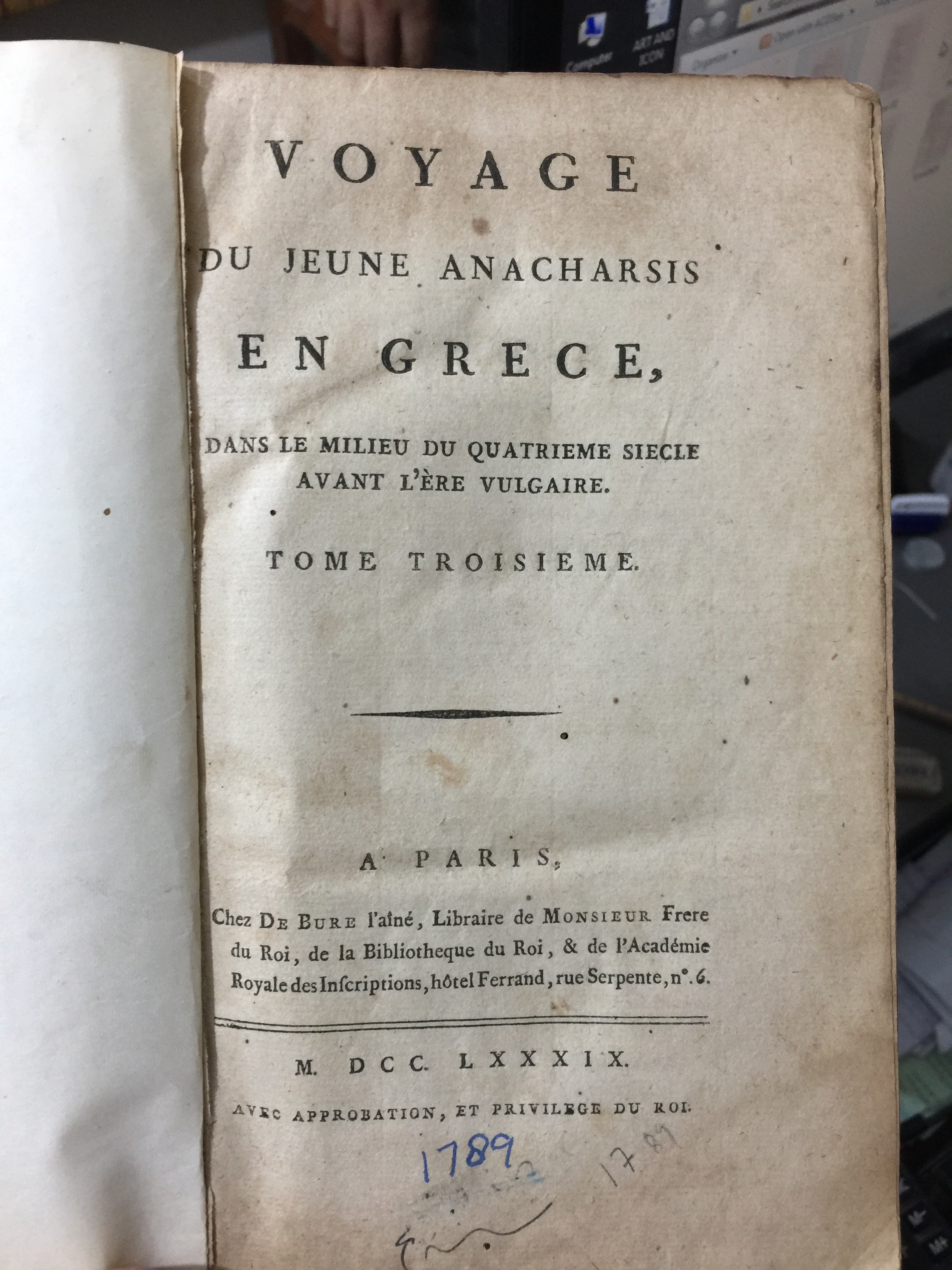

Second edition of Jean-Jacques Barthelemy’s novel, Travels of Anarcharsis the Younger in Greece, published in 1789 by De Bure.

Safdar has placed his prize possessions – rare first and second editions – in a small, windowless room, which serves as an office of sorts. He pulls out a second edition of French archaeologist Jean-Jacques Barthelemy’s novel, Voyage Du Jeune Anacharsis En Grece (Travels of Anarcharsis the Younger in Greece), published in 1789, by De Bure. It is in surprisingly good condition, but only one volume of a larger set. He also shows me an 1888 translation (first edition) of Iranian poet Sheikh Sa’adi of Shiraz, by Sir Richard Burton. It is titled Tales from the Gulistan or Rose Garden and includes illustrations by John Kettelwell. There is in his possession a second edition of the Muraqqa-i-Chughtai, Paintings of M.A. Rahman Chughtai with about Fifty Plates, published in 1928 by the Jahangir Book Club, in Chabuk Swaran, Lahore. It includes a full text of Diwan-i-Ghalib (the poetry of Mirza Ghalib). When I ask him if he has chemically treated these volumes to preserve them, he replies in a manner that displays a distrust of the process: “No…no.” Instead, he says he “fumigates” the shop and the books with DDT. Rodent droppings line the mounds like ants.

After Safdar’s father, Safdar Mehdi, migrated to Karachi in 1951, he first started working in the Greenwhich Bookshop on Elphinstone Street (now Zebunnisa Street). His passion for books drove him to converse with customers at length on subjects that were close to his heart, such as history. As a result, they befriended him and his persona morphed into something bigger than the shop itself. “When the Nawab of Bahawalpur [Sir Saddiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi V] would visit the bookshop in those days,” says Safdar, “he would call out after my father: ‘Safdar!’ Where is Safdar?’” Sherbaz Mazari too was a regular back then.

A couple of years later, Mehdi set up a stall on the footpath of Regal Chowk. “Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto visited the stall regularly,” says Safdar, “and donated journals and magazines.” It was around this time that Mehdi began supplying books to public libraries and universities, while continuing to sell antique and rare volumes to individual customers, which was his area of focus. “He had a book-import license, and would order books from the UK,” says Safdar, adding, “back then, an import license was a must.”

After running the stall for about three years, Mehdi opened Everyman Book House on Burnes Road. In 1968, the shop shifted to Fareed Chambers on Victoria Road, where it remained until 10 months ago. In 1972, Mehdi launched Indus Publications, with the aim of reprinting out-of-print titles that were in demand – works on the history of the subcontinent in particular – and books that were needed for research. “The first title we reprinted was Major-General Malcolm Robert Haig’s Indus Delta Country: A Memoir, originally published in 1894,” says Safdar.

Safdar spent a lot of time in the shop in Fareed Chambers while growing up. “On my way home from school, I would stop by at the shop to see my father,” he says. “I would complain to him – ‘What is this boring work you do Abba?’”

“Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was a regular customer before he became prime minister,” says Safdar. “He was a collector and would get my father to order books for him.” Later, Bhutto invited Mehdi to come and see his library at 70 Clifton, according to Safdar. “As my father climbed up the winding stairwell inside the library, he knocked over one of the decoration pieces by mistake,” says Safdar. “It missed Mr Bhutto’s head by several inches and fell on his shoulder. He shouted at my father. By then, he was prime minister.”

Safdar joined his father in the book trade in 1990. “Unlike him, I am interested less in history and more in current affairs,” he says. Mehdi retired in 2006 and passed away on August 18, 2018. He lies buried in the Wadia Hussain graveyard, near the M-9 Motorway. The shop, meanwhile, is dying a slower death. It continues to cater to individual customers and orders titles from publishing houses in the US, UK and India, including Cambridge University Press, John Wiley & Sons and Thames & Hudson. “Indus Publications is one of many suppliers to government institutions,” says Safdar. He has ordered reprints and new books for the Sindh Archives. But he does not want to be the main supplier for government institutions. “They ask for a high commission – usually 25 per cent to 35 per cent,” he says. “And selling rare books to them is a lengthy process that goes through various stages of ‘approval.’ And since, for whatever reasons, they do not have much of a budget, they try to negotiate prices.”

The future does not look bright for the book trade in Pakistan. “People are investing less in books as their prices have gone up,” says Safdar, “particularly the price of imported books.” If he had it his way, he would prefer to shift to a space on the ground floor, overlooking the main road, where his shop would be visible to the public. Nevertheless, a mischevious grin remains plastered on his face, even when he talks on serious subjects. He recalls the time when an order of books being delivered from the airport was snatched at gunpoint in 1998. “If they had known that the boxes were full of books, I doubt they would have taken them,” he says.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com