Home is Where the Heart is

By Zohra Nasir | Art Line | Published 12 years ago

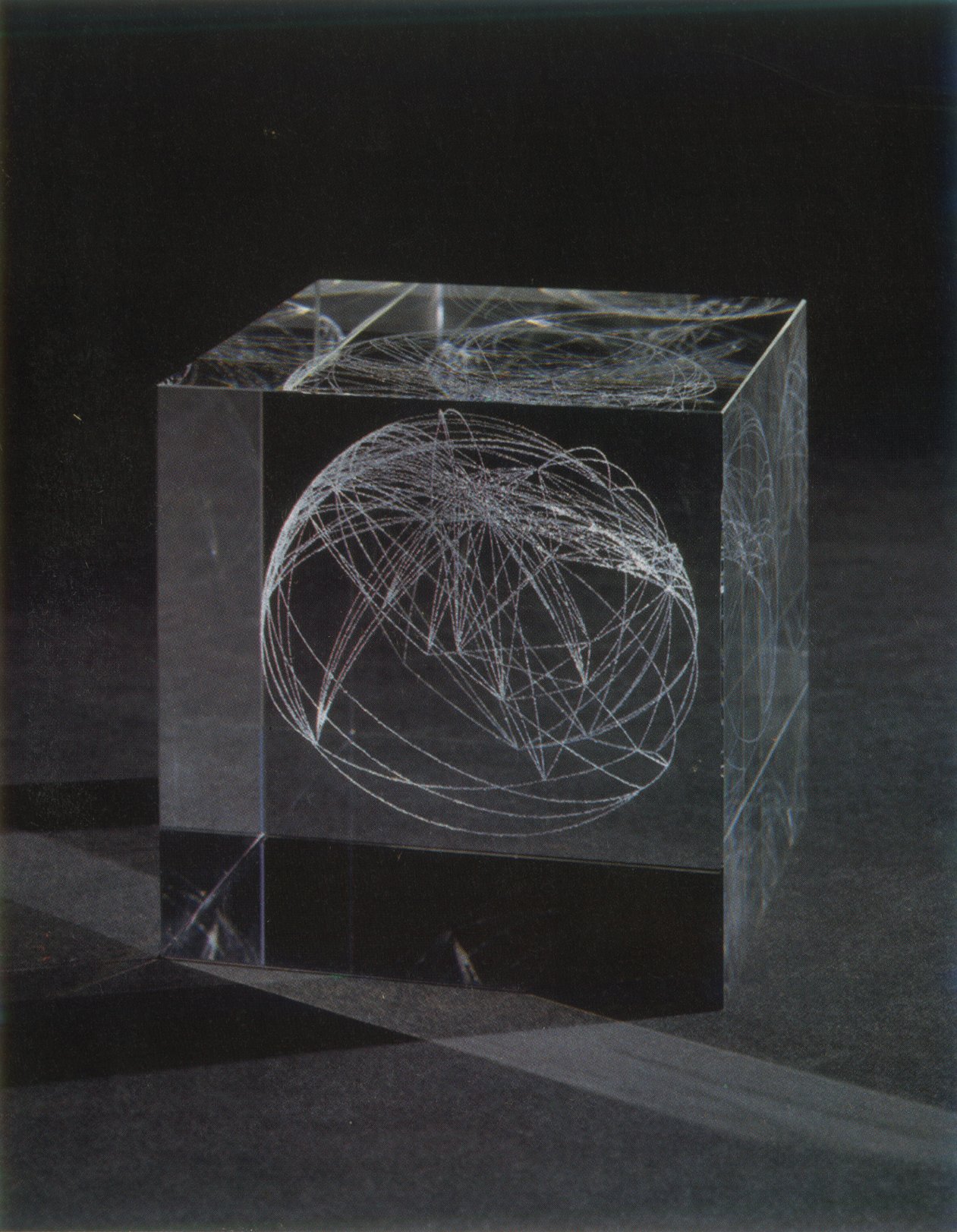

In the centre of the Homelands exhibition at the VM Art Gallery, a large glass case showcased a small glass cube. At first I thought, “They’ve forgotten to put the piece in there,” but I walked over, foolishly leaned and squinted, and saw the truth in this empty box: It was Langlands and Bell’s ‘www.2000,’ a laser etching in optical glass of the Earth, mapped only through air routes. This ethereal sphere, suspended in nothingness, communicated the thrust of the whole show to me: Our world is one in perpetual motion, in which only that is real which is connected to something else, and in this motion of the world, we all must move — changing our costumes, habits, desires and, consequently, our notions of who we are. However, all this unstoppable motion also comes with a sense of loss. Rachel Lowe managed to capture this perfectly in ‘A Letter to an Unknown Person No. 5,’ a video showing the artist sketching the scenery passing by the window of a moving car, but unable to capture a moment in time, as the scenery keeps shifting.

The exhibition, organised by the British Council, offered a selection of the works of 19 artists from all over the world, who engaged with themes of transition, identity, fusion of cultures and eradication of the past. Sketch work, sculpture, photography, sound and video montages were up on display, plenty to interest any viewer, and engage all the senses.

The exhibition, organised by the British Council, offered a selection of the works of 19 artists from all over the world, who engaged with themes of transition, identity, fusion of cultures and eradication of the past. Sketch work, sculpture, photography, sound and video montages were up on display, plenty to interest any viewer, and engage all the senses.

The collection asked some urgent questions pertinent to our lives today: What does ‘home’ mean to us products of globalisation? In a world that is constantly sending multiple influences our way, how do we define ourselves? Is it through geography, dress, language, religion or something else entirely? What if all these things conflict with each other? How should we label ourselves? In fact, must we label ourselves?

Suki Dhanda’s photographs from her series ‘Shopna,’ documented the life of a Bangladeshi-British Muslim teenager and showed accommodation, assimilation and acculturation taking place. The massive images dominated the gallery, showing how so many British Muslims lived in two worlds melded together: dressed in conservative, traditional clothing, the girls pictured ate western food and played pool in a community centre where anti-Iraq war pamphlets hobnobbed with self-help manuals. Similarly, Zineb Sedira offered a series of three videos showing a grandmother, mother, and daughter communicating fluently in three different languages in three different countries. It showed that even within very close familial ties, identity can mean entirely different things to different generations and that the modern conception of family is anything but stable. The modern family can move across continents and cultures — how then can it define a core? Such pieces call into question our little mythologies of identity and belonging.

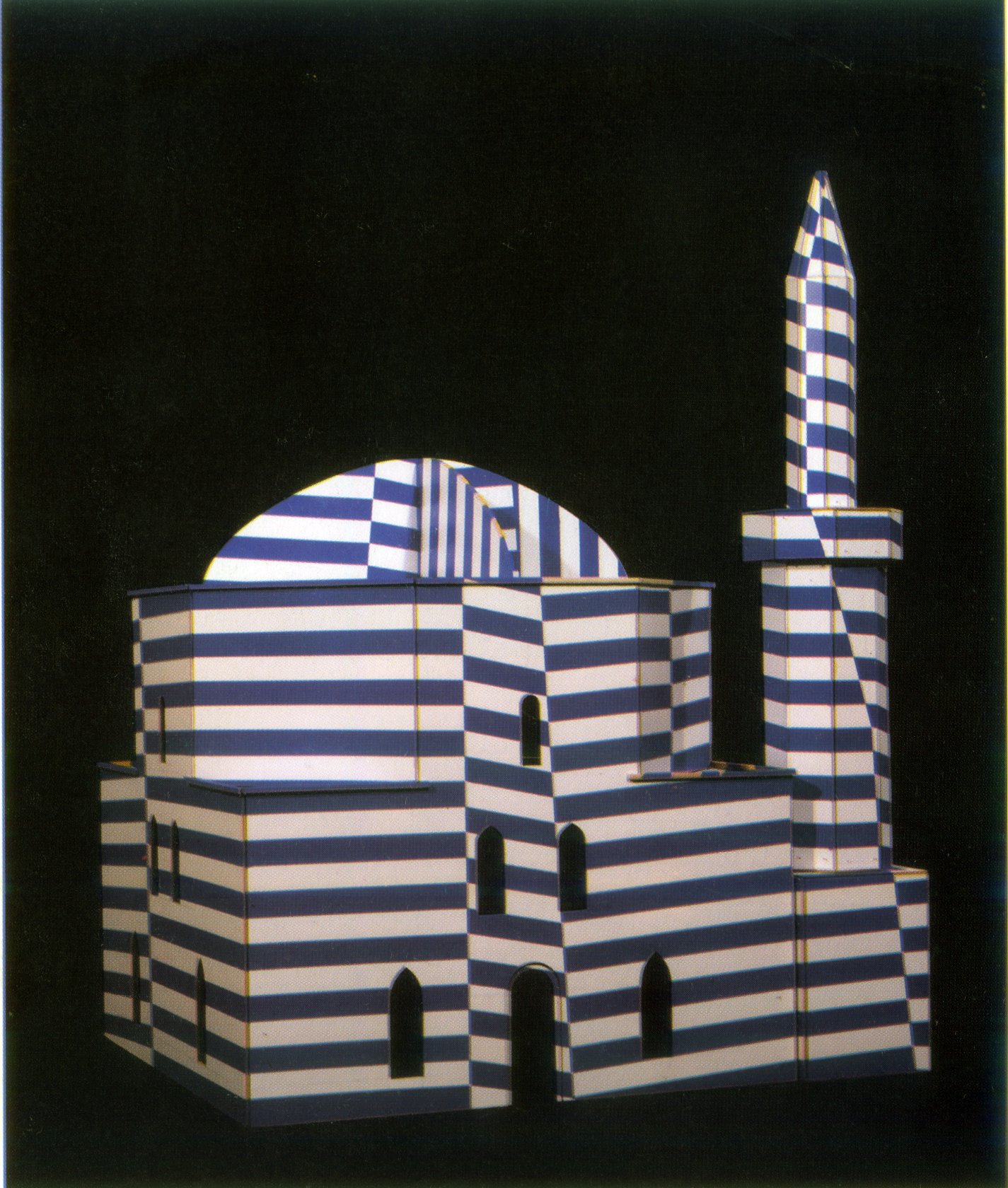

The most eye-catching piece of the exhibition was Nathan Coley’s ‘Camouflage Bayrakli Mosque.’ The mosque, one of the only mosques in use in Belgrade, had a troubled history. It was built by the Turks, served as a Church under Austrian rule, and then became a mosque again, but one that frequently came under attack as a symbol of an aggressive people and religion. Covered in blue and white stripes, Coley’s hardboard version seems an innocuous toy, and it is bewildering to think that a lifeless building could cause so much conflict.

Ownership of places is often marked by conflict, and this shows most starkly in the concept of borders. Borders were explored in Jimmie Durham’s ‘Our House,’ which showed a childlike sketch conception of a peaceful “us” and a vague but violent “them” on the side of a high fence. Paul Graham’s ‘Roundabout, Andersontown, Belfast,’ as well as Anthony Lam’s ‘Citizenship and Nationality’ also explored the undercurrent of hostility associated with borders. Raymond Moore had photographed border towns in the UK, wire and wood fences against rolling hills and open sky. Although this made no obvious political statement, it affected me. The borders seemed like laughably flimsy things, unable to prevent the flow of what naturally belonged to the earth — the wind, sunlight, land, birds, shadow — but arbitrarily keeping humans from flowing easily from one place to another.

Ownership of places is often marked by conflict, and this shows most starkly in the concept of borders. Borders were explored in Jimmie Durham’s ‘Our House,’ which showed a childlike sketch conception of a peaceful “us” and a vague but violent “them” on the side of a high fence. Paul Graham’s ‘Roundabout, Andersontown, Belfast,’ as well as Anthony Lam’s ‘Citizenship and Nationality’ also explored the undercurrent of hostility associated with borders. Raymond Moore had photographed border towns in the UK, wire and wood fences against rolling hills and open sky. Although this made no obvious political statement, it affected me. The borders seemed like laughably flimsy things, unable to prevent the flow of what naturally belonged to the earth — the wind, sunlight, land, birds, shadow — but arbitrarily keeping humans from flowing easily from one place to another.

Among the more striking pieces were Cornelia Parker’s ‘Meteorite lands on Buckingham Palace’ and ‘Meteorite Lands on St Paul’s Cathedral.’ Parker stacked up maps of London and used heated pieces of a meteorite to burn away the spots where these landmarks stood. Speaking to The Guardian, Parker said of a similar work: “It takes a fraction of a second for a meteor to hit the earth, or for you to say something that might change everything.” Her work often re-imagines the familiar through destruction and points to the frailty of all that we hold sacred. What was interesting to me was that while these two integral parts of the London landscape could be easily removed, the shock waves did not flow over to the rest of the metropolis.

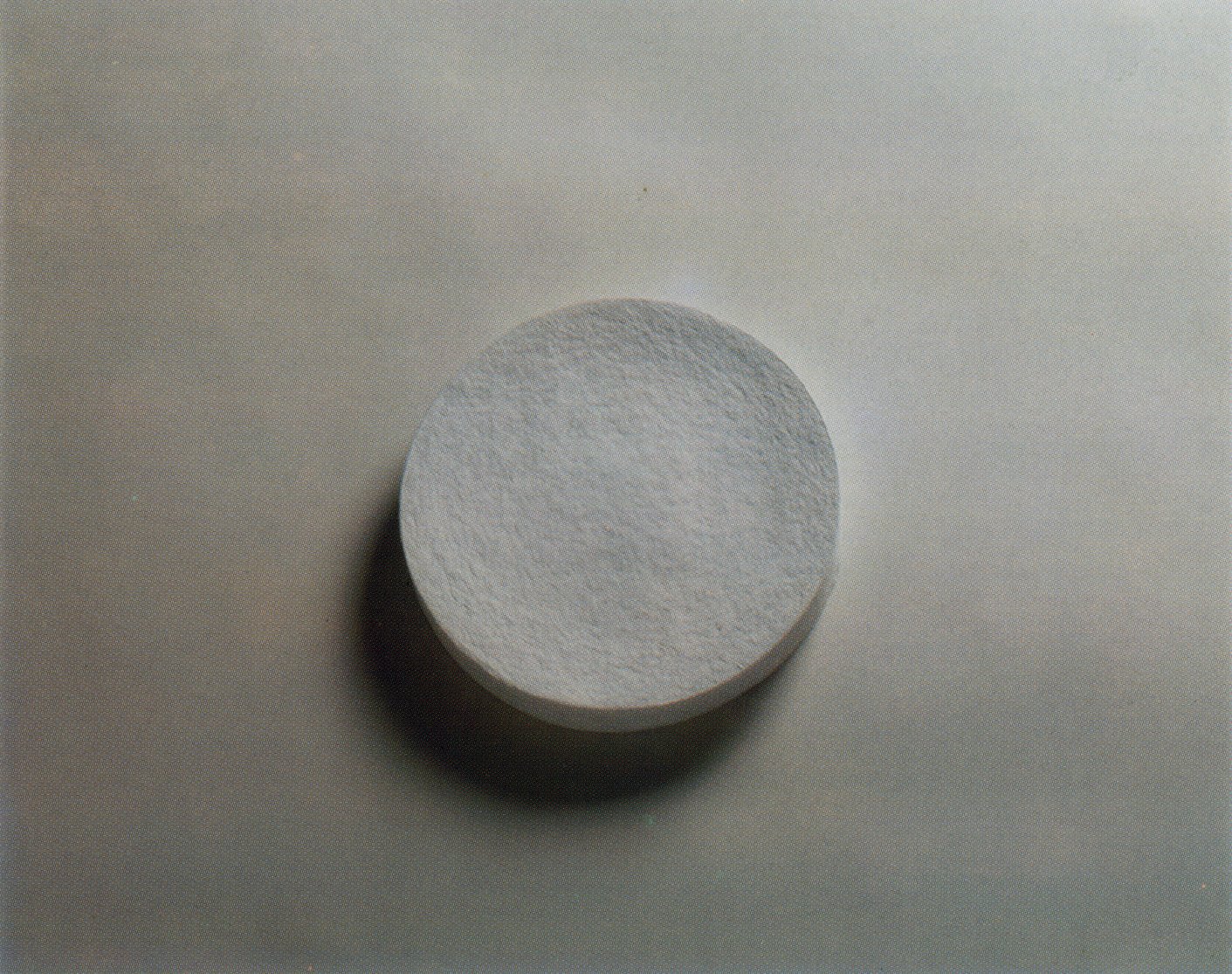

A very interesting take on knowledge was Graham Gussin’s Ghost,’ in which a pulped version of The Cambridge Atlas of the Stars created a blank disc where the original information was no longer visible. Turning all this information into a tangible object rendered the knowledge useless. To me, this was a negative comment on our lifestyles, obsessed with the compact and the material, rather than with meaning. More re-invention of knowledge came through in David Shrigley’s ‘Imagine the Green is Red.’ These words were handwritten on a sign and inserted into a beautiful lawn — the artist through this seemed to be staking a claim to perceive the world in an atypical way, opening the door for every viewer to control his perception of the world rather than simply perceiving it as told.

A very interesting take on knowledge was Graham Gussin’s Ghost,’ in which a pulped version of The Cambridge Atlas of the Stars created a blank disc where the original information was no longer visible. Turning all this information into a tangible object rendered the knowledge useless. To me, this was a negative comment on our lifestyles, obsessed with the compact and the material, rather than with meaning. More re-invention of knowledge came through in David Shrigley’s ‘Imagine the Green is Red.’ These words were handwritten on a sign and inserted into a beautiful lawn — the artist through this seemed to be staking a claim to perceive the world in an atypical way, opening the door for every viewer to control his perception of the world rather than simply perceiving it as told.

But the most haunting piece had to be Susan Hiller’s ‘The Last Silent Movie.’ The videoless film was a mash-up of recordings of 25 languages that are either dying or extinct. For short bursts, the viewer hears people talking in various marginalised languages, with English subtitles to understand the content. There are lullabies, fables, songs, proverbs and dialogue — faceless people talk about life and sometimes about the threats that their own culture and language (now dead!), face especially from the “white man” and his “lies.” It is horribly sad to think that with the death of these languages, dies the wisdom and the history of entire cultures. The cost of assimilation, then, can be extremely high.

Having looked at and thought about all these and many other pieces exhibited, my predominant thought was, this is odd. Odd, to be standing in the middle of Karachi — this frantic, violent Urdu-speaking city, rooted in deep tradition and yet changing with every second — staring at objects that strangers from all over the world had made, chiding me for having lost my identity. Stranger still, to be noting these thoughts down in English on a smart phone — both things that gave me access to knowledge and the whole world, but may well have cut me off from my own reality.

Strangest of all, to know that the man turning on the lights for me was idly listening to Indian music on his phone, blissfully immune to all the weighty questions the exhibition all around him was asking, and that after exiting the gallery, I, too, was going to step out and slip comfortably back into my everyday life, full of contradictions as it was. I was not sure whether anyone should, in fact, be casting judgment upon my warped notion of ‘home,’ ‘heart’ and ‘reality.’ To say that a Pakistani family eating Thai food in front of the Star World channel is not as valid as one having homemade karahi at a dinner table seemed absurd. And yet, this question of identity and the pain of loss wore heavily upon me.

This issue of identity is not one that any of us grapple with moment to moment. We tend to take things simply as they are. While art may make us talk about the big questions, those conversations happen easily in the confines of galleries and on the pages of magazines, forgotten in day-to-day existence. This time, however, the thoughts lingered a little longer. Homelands did what good art ideally does — it made me sit up and think. Perhaps we could all use a little soul-searching and save ourselves from a sense of loss. n