The Art of Protest

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 21 years ago

For an artist whose name has always been synonymous with protest art, A.R. Nagori’s exhibition at V.M. Gallery was true to form. Insightful, fearless and often funny, his paintings continue to challenge the status quo, and he still attacks with deadly accuracy.

Critical art, evolving out of an amalgam of realism, modernity and politics, enjoyed currency during the two world wars. It was defined through the tension between individual creativity and official criticism and censorship, in changing historical circumstances. But today it is only a testimonial of its times. The ability of this art to thwart the state, as it did in countries like Russia and Germany, has now diminished considerably. However, on a minor scale, as late as the mid-90s, dissident art was making news. Relatively unknown here, Japanese artists Nobotuki Ohura and Yoshika Shimada stirred up a storm of conservative outrage when it was discovered that their artworks violated the state policies of their country. One was denied exhibition space and the other’s art catalogues were burned.

On home ground, politically engaged social realism is no longer the taboo genre it was when censorship was first imposed on Nagori’s Anti-Militarism and Violence exhibition sponsored by the PNCA in 1982. Government censure worked wonders, giving his work the publicity it needed to be noticed. Immediately following this ban, the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) took on the challenge of exhibiting his work, and Nagori the political artist was born. His Anti-Dictatorship exhibition at Indus Gallery in 1986-88 was held in an atmosphere of threats and personal risk, but by this time he was committed to his cause. ‘Crisis on the Road to Democracy’ was a critical commentary on Zia’s legacy. His incisive portrayal attracted a fair amount of foreign press and he gained international acclaim as an artist of social protest. Issues relating to the exploitation of women and children have always been close to his heart. In this context, an exhibition at the Indus Gallery in 1990, called ‘Women of Myth and Reality,’ drew attention to gender injustices. Having grown up in the Sindh region, Nagori has an instinctive feel for the land and its people. Exploring the lives of the Bheel and Kohli tribes through his imagery, he documented a caustic account of bonded labour under feudalism in another major exhibition, ‘Black Amongst the Black,’ in 1994.

Presently exhibiting after a hiatus of 10 years, Nagori’s show at V. M., called the ‘Return to Sphinx,’ targets a number of vital issues. It questions the government’s nuclear standing, its education policies, insensitivity to environmental pollution and failure to hydrate the thirsty landscape of Thar, and his pet peeve, parliamentary wheeling dealing and power play. ‘Kari (black) Karachi’ is a composite but heart wrenching piece on the present status of Karachi, a city robbed of all vestiges of natural beauty. Nagori paints a woodcutter/marauder, who, having chopped the last tree, now eyes the Quaid’s Mazar in anticipation, while a denuded, lethargically reclining figure suggests the symbolic city. A blackened sea and the sinking hulk of the Tasman spirit tell their own story.

Presently exhibiting after a hiatus of 10 years, Nagori’s show at V. M., called the ‘Return to Sphinx,’ targets a number of vital issues. It questions the government’s nuclear standing, its education policies, insensitivity to environmental pollution and failure to hydrate the thirsty landscape of Thar, and his pet peeve, parliamentary wheeling dealing and power play. ‘Kari (black) Karachi’ is a composite but heart wrenching piece on the present status of Karachi, a city robbed of all vestiges of natural beauty. Nagori paints a woodcutter/marauder, who, having chopped the last tree, now eyes the Quaid’s Mazar in anticipation, while a denuded, lethargically reclining figure suggests the symbolic city. A blackened sea and the sinking hulk of the Tasman spirit tell their own story.

The artist’s anti-nuclear stance is played to good effect through paradoxes in ‘Nuke Knight’ and ‘Nuke Delivery.’ The former painted against the backdrop of Nagori’s love for ancient history and mythology, shows a knight of the crusades in chain-mail armour wielding a missile instead of the customary lance. The latter mocks at technology being delivered in a pushcart through the ruined city of Hyderabad, where baying wolves and charred remains strike its death knell. Exposing the inadequacy of the education system, Nagori paints intellectuals at universities as the proverbial monkeys that see, hear and speak no evil, while the poor students scramble for knowledge in a wasteland of ignorance.

‘Culture Shock’ exposes the decadence and depravation rampant in the corridors of power. Similarly, ‘Madam X’ is all about priestly misconduct, a scandal that rocked Islamabad some time ago. For Nagori the colour green symbolises his country and ‘Vultures Over Green Lady’ thus becomes painfully self-explanatory.

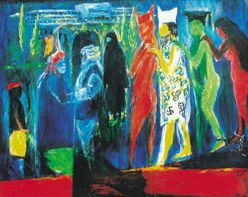

The major thrust of this exhibition is to prod national politics with the intention of exposing its deeper and inherent weaknesses through overt symbolism. The artist takes direct hits in his Assembly Line series of paintings to lampoon suspect (corpulent) legislative members meeting “belly to belly,” and hijab-clad women fundamentalists espousing generalisations, while the real power-brokers move into the fast lane. Children’s jungle book fables are humourously reinvented by the artist to satirise power politics. ‘Blue King Well Served’ sketches a wily jackal hoodwinking the all-powerful lions and tigers into serving him.

If Nagori’s concepts are hard-hitting, his imagery and colour preferences are even more so. His academic credentials are certified by none other than stalwarts Anna Molka and Khalid Ahmed of Punjab University. He was painting what he calls “pure aesthetics” before he stumbled upon the rocky road of protest and criticism. From then onwards it was the message that dictated the style, form and content of his work. Working in a semi-abstract mode he opts for a raw, naïve expression which best brings out the inherent pungency of his statements. Scorching, brilliant colours like deep reds, blues and yellows are also strategically used to maximum effect. ‘Mosque Desecrated’ is a good example of maximising the effect of just one colour, red. Texture, created by layers of colours with a knife or a rough slow moving brush, again evoke a primitive earthiness that jars the senses. Moreover, his defined horizontal, vertical, diagonal and oval division of space is another drastic measure that literally lends a cutting edge to some of his strong compositions like ‘Chand Raat.’

If Nagori’s concepts are hard-hitting, his imagery and colour preferences are even more so. His academic credentials are certified by none other than stalwarts Anna Molka and Khalid Ahmed of Punjab University. He was painting what he calls “pure aesthetics” before he stumbled upon the rocky road of protest and criticism. From then onwards it was the message that dictated the style, form and content of his work. Working in a semi-abstract mode he opts for a raw, naïve expression which best brings out the inherent pungency of his statements. Scorching, brilliant colours like deep reds, blues and yellows are also strategically used to maximum effect. ‘Mosque Desecrated’ is a good example of maximising the effect of just one colour, red. Texture, created by layers of colours with a knife or a rough slow moving brush, again evoke a primitive earthiness that jars the senses. Moreover, his defined horizontal, vertical, diagonal and oval division of space is another drastic measure that literally lends a cutting edge to some of his strong compositions like ‘Chand Raat.’

Nagori’s art took a definitive turn towards critical comment in 1982 when his exhibition in support of the Palestinian cause was banned from public display. But his commitment to social causes goes back in time. “When agitation against Ayub Khan’s martial law was going on, I was a student leader with Mairaj Mohammad Khan,” he disclosed, throwing light on the development of his inner calling. Today political protest may be a popular expression of defiance among artists, but just two decades ago it was a lone crusade pioneered by Nagori. Unwavering in his resolve, he practiced what he preached, ironically as a grade 20 government servant. He founded the fine arts department at the Sindh University, Jamshoro, and remained its head for 20 years before he took premature retirement in 1995, at age 55. How can an artist cohabit with the establishment and yet remain staunchly anti-establishment?

Nagori’s tenure as a government employee was fraught with confrontation. He was accused of being “too radical and too drastic,” was often issued letters of warning, was even suspended and went without salary for a year. “Among the few things that saved me,” he feels, “was the fact that Sindh was a very sensitive area and I had strong student backing not just in my university but also among students in Punjab University. The government refrained from picking on me for fear of student agitation. Secondly, I was sincere to my work and I did my best. Academically, I was very sound. Practically, my contribution was there too. Being Chairman Curriculum Committee Art Teachers’ Programme, Ministry of Education in 1984 and as advisor for the proposed Federal College of Art Jamshoro and preparing its feasibility is a case in point. Moreover, my solo exhibitions were few and far between and not a constant irritant. And their content appealed mainly to the intelligentsia, the common man seldom saw it. This conformed to Zia-ul-Haq’s policy which allowed the English press to cover such events but not the Urdu press. What they did not realise was that through the English media, news of my work travelled into the international press, where the element of protest was well acknowledged. I even earned appreciation from the renowned anti-nuclear physicist/activist Carl Sagan.”

Today it is easy to understand why state awards have not and may never come his way, but one wonders why human rights organisations are not acknowledging his contribution to the cause? Is this not a sorry reflection on the value of art which is being used for the service of humanity?