No Magic Wand for Education

By Zubeida Mustafa | Cover Story | Published 7 years ago

Learning the hard way: Sitting on the ground at a government school.

As we enter the ‘Naya Pakistan’ age with high hopes, it would be pertinent to ask two questions about the proposed education reforms that are on the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) agenda.

Does the PTI government have the vision to bring about the right changes in the education sector? If so, how will it realise its vision?

Clearly, no one has a magic wand that can be waved to transform the state of education in Pakistan. The malaise runs deep and this is an area which has never received any serious thought.

Education comprises many sectors and sub-sectors, and even the best educationists in Pakistan fail to understand the close correlation among the various areas. These champions of education invariably become advocates of their own areas of expertise, which is of no help. If one is drumming the cause of university education without addressing the problems at the primary level, nothing will change. If another is more down to earth and focusing on primary schools, but has no understanding of the need for a child to be taught in their mother tongue, that will make no impact either. A comprehensive approach is needed.

Listening to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s maiden address to the nation, I felt he has the vision but no strategy. He seems to understand some of the basic issues which are:

• Need for access to affordable and good education for all.

• Importance of upgrading government schools.

• Regulating the private sector.

• Madrassa reforms.

• Investing bigger sums in the education sector.

One believes Imran Khan still has to chalk out a strategy to achieve the proclaimed goals and that is not going to be easy.

Here, I will point out some key areas in which action could be taken to set the ball rolling.

Learning rote-style: Students at a madrassa.

The first step should be to clarifiy the area of jurisdiction. The impression one gets is that the leaders seem to have forgotten that education is a subject that was devolved to the provinces by the 18th Amendment of the constitution in 2010. Since 2013, when the People’s Party — the main champion of provincial autonomy — lost power over the federal government, there has been a quiet struggle behind the scenes by Islamabad to regain its control over education in bits and pieces. The mechanism of the Inter-Provincial Education Ministers’ Conference was employed to draft a new education policy and draw up a new curricula. Sindh never participated wholeheartedly in this process.

Imran Khan has been talking about education’s myriad problems and has promised to rectify them. He may succeed, to an extent, in Islamabad, KP, Punjab and Balochistan because the first three are under the PTI, while Balochistan is governed by a coalition. However, Sindh, with the worst record in the education sector among the provinces, is not under the PTI. Mindful of this, Imran Khan qualified his statements by stating that he will act in cooperation with the Sindh government.

An indicator of things to come is the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP)’s strong reaction to this stance. MNA Nafisa Shah, the information secretary of the PPP, reacted by saying that PM Khan was clueless about the provincial rights guaranteed under the Constitution. “It seems he doesn’t know that governance is a multi-layered subject,” she added. She reminded the prime minister that “to reform the health and education sectors he will have to talk to the provinces which, in fact, give effect to policies.” Another constitutional battle in the province is the last thing Sindh now needs to raise the standard of education.

The large number of out-of school children in Pakistan – approximately 23 million by the government’s own count – has been noted by the prime minister and it is a relief that he understands the gravity of this issue. I hope he is aware that a huge chunk of these are girls. In this case the gender factor will have to be carefully addressed. Not only do girls need better access to schools, but also educational institutions with boundary walls, toilets, electricity and drinking water near their homes. The societal barriers are tougher for girls than for boys and society’s patriarchal mindset has to be taken into consideration. Although the education of girls has gained more widespread parental acceptance, it still has to be pursued vigorously. Misogyny continues to abound.

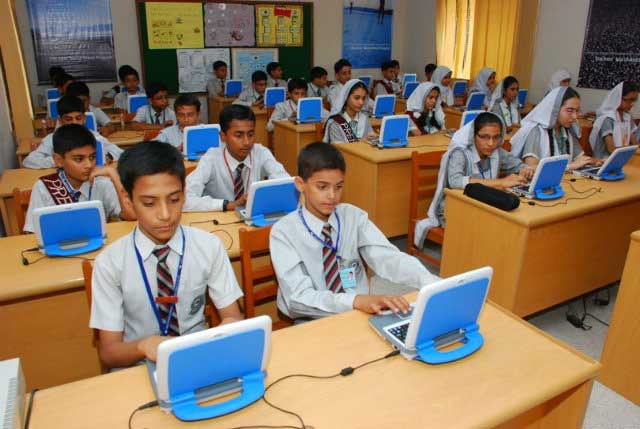

Learning in comfort: Private school students benefit from technology.

Education Minister Shafqat Mahmood has been speaking of innovative initiatives to expand the school network. Before embarking on any venture, he should visit some schools in the backwaters of Pakistan to understand that school structures are not the only thing we need. Trained teachers, good textbooks and rational management, which includes monitoring and a meaningful exam system, are also needed to make these schools functional and useful. Quality is as important as quantity.

Expansion of schools has to be a planned process. For instance, a stupendous number of schools are only one or two-room structures with one teacher. Neither is it logical to have 150,000 primary schools and only 49,000 middle schools. This results in a high dropout rate, since many children after passing their primary level, have no place to go and their education ends abruptly at age 10.

Since school education is the state’s responsibility under Article 25-A, attention is inevitably focused on schools. And there has been criminal neglect of this sector. The state has never taken ownership, despite its constitutional obligation to do so and, hence, it has emerged as a public-private partnership sector. Academic quality has been provided by the private sector with the support of affluent parents. The public sector has tried to cater to the needs of the huge majority, but quality has been sacrificed as funding has been measly.

Imran Khan has recognised this basic flaw in our system and has promised to address the education in the public sector, so that more children move back to the public sector schools that have gradually been drained of students.

There is also a need for social regulation of the private sector that is necessary to remove the disparity and anomalies that have fragmented our education system. With so many systems operating in the country concurrently, socio-economic fissures have appeared which have made us one of the most unequal societies in the world. The gap between the rich and the poor keeps growing – in large part it is directly related to the quality of education received.

If we could have the same system but of a higher standard with equal opportunities, it would benefit the country considerably. What we have at present are a handful of high quality elitist institutions catering to the needs of the wealthy who control the reins of power to govern the poor, illiterate, underprivileged masses who are denied good education.

If school education is steered in the right direction, higher and professional education will become easier to manage. A system of public-private partnership in tertiary and higher education may work better. Unlike school education, it would call for more diversity and would have to be closely linked to the market and the academia. In the absence of disparity, merit would be the main criterion for admission to universities and to employment.

State-of-the-art equipment at a higher education institution.

All this calls for increased funding of this sector. But it must be transparent, because the education sector is notorious for rampant corruption. Moreover, the increase in funding must be planned and coordinated with the capacity created. If that is not done wisely, pumping money randomly in this sector will lead to corruption as has happened in recent years.

These questions are all important, but there are two issues that are overarching and affect every sector. One is language in education and the other is religious instruction. They have profound implications for education as well as society itself.

We are a country which has still not been able to decide in which language we should teach our children. The elite and their hangers-on, who benefit from them, want their children to learn English and also to study all their subjects in English as well. They are anglicised and want their children to be the same as that gives them a special status socially and many advantages, both economically and politically. The underprivileged also want their children to be taught in English, even though the teachers are not familiar with the language. This is undermining our education system. The indigenous languages are being destroyed. The children, by and large, have no proficiency in English and their cognitive thinking is stunted. As a result the majority derive no benefit from their English-based education while the small elite minority, because of their better education, move on and society is further stratified.

Another major point to ponder is, how religion should be taught to Muslim students. If the aim is to inculcate true Islamic values in them, there is need to rethink the pedagogy adopted for Islamic Studies. Instead of addressing this issue, policymakers have periodically been increasing the religious content in the curricula on the false premise that this approach will resolve the problem of intolerance and extremism.

In his maiden speech, the prime minister spoke about the madressahs, another challenge governments in office have faced since these institutions proliferated in the Zia years. Imran Khan spoke about reforming these institutions so that they develop the capacity to produce engineers, doctors and other professionals. How he does it is the moot question, given the fact that previous governments failed to even get the madressahs to modernise some of their curricula and disclose their sources of funding.

A concerted effort is needed to change the state of education in Pakistan. Issues must not be prioritised. All issues have to be addressed concurrently if any impact is to be made.

Zubeida Mustafa is a veteran journalist of over 40 years and has written extensively on the social sector and education. She is also the author of four books including My Dawn Years.

Zubeida Mustafa is a senior journalist. She writes on a variety of subjects but her interest has mainly been in the social sector which she has covered extensively. She has investigated in-depth issues such as education, health care, women’s empowerment, children’s rights and the lives of ordinary people.