Dispatches to a Departed Hero: Artists Give Tribute To Salmaan Taseer

By Ilona Yousuf | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 13 years ago

Shortly after the assassination of Salman Taseer in the first few days of 2011, members of the artist community began to approach Asad Hayee, the curator of Rohtas Gallery, and Sanam Taseer, owner of the Drawing Room Gallery. Their conversation during these visits expressed a common concern: they were horrified at the message propagated by the killing and subsequent political and social reaction which followed the Governor’s support of Aasia Bibi — accused of blasphemy by her co-workers. The wave of intolerance and inhumanity, already rampant in the two years preceding the event, appeared to have spiralled out of control. Fanned by the religious right, the glorification of Taseer’s assassin signalled a deep and tragic malaise.

With repeated visits expressing the artists’ desire to produce works of art in response to the event, Hayee and Sanam Taseer approached Salima Hashmi for curatorial advice in organising an exhibition which would reflect their preoccupations. A prospective list of 50 artists was drawn up, and a three-part series of exhibitions was planned, organised by different curators and titled Letters to Taseer. In the absence of a large public venue like Alhamra, which was booked far ahead and unable to provide their space, the size constraints of the gallery, in this case The Drawing Room, had to be kept in mind when collecting the works to be displayed.

Part I of the series, curated by Salima Hashmi, featured nine mostly large-scale works in various genres, from installation to print and painting, executed by established and emerging artists.

If Rashid Rana’s ‘Red Carpet I,’ executed in 2007, belongs to a time preceding this dark period, it is certainly symptomatic of the present. Fusing traditional motifs with modern technology, this panoramic print is constructed of images from local abattoirs. Contrasting with the intricate, idyllic beauty of the hand-woven carpet, in this case woven with a floral theme, is a telling statement on the condition of our own garden. Imran Mudassar’s much smaller scale ‘Untitled,’ using black poster paint and pencil on paper, uses a similar traditional theme, this time a Mughal fresco, in an entirely different manner. Surrounded by outlined borders of buds and arabesques, the perfection of formal arrangement and balance, is a black heart, from which silhouettes of flies crawl into and stain the surrounding motifs.

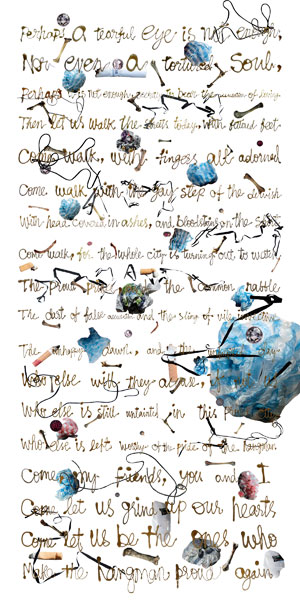

With its multiple references, Faiza Butt’s dura-trans two prints mounted on light-boxes use Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poem ‘Aaj Bazaar Mein Paa-ba-jaulan Chalo’. In the Urdu version, the text is embellished: some words are made up of elaborate jewelled necklaces and rosaries, as well as the graceful arabesques of Islamic art; others are decorated with daggers and swords, and the entire surface is littered with fragments of rope and bones. In the English version, written in a loose looping hand, Butt strews the text with crumpled plastic bags, fragments of bones, ropes and nooses, and cigarette butts. Both prints appear to suggest that we have thrown away all compassion and humanity; or at the very least, strangled it. Although, if one looks closely one discerns beads and crystals amongst the trash. Mohammad Ali Talpur’s ‘Mashq,’ drawn in ink on paper, is made up of a dense map of repeated fetal shapes. At first view these resemble the dense patterns of op-art; but the shapes carry the idea of the strength of numbers and the uniform dullness of repetition.

With its multiple references, Faiza Butt’s dura-trans two prints mounted on light-boxes use Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poem ‘Aaj Bazaar Mein Paa-ba-jaulan Chalo’. In the Urdu version, the text is embellished: some words are made up of elaborate jewelled necklaces and rosaries, as well as the graceful arabesques of Islamic art; others are decorated with daggers and swords, and the entire surface is littered with fragments of rope and bones. In the English version, written in a loose looping hand, Butt strews the text with crumpled plastic bags, fragments of bones, ropes and nooses, and cigarette butts. Both prints appear to suggest that we have thrown away all compassion and humanity; or at the very least, strangled it. Although, if one looks closely one discerns beads and crystals amongst the trash. Mohammad Ali Talpur’s ‘Mashq,’ drawn in ink on paper, is made up of a dense map of repeated fetal shapes. At first view these resemble the dense patterns of op-art; but the shapes carry the idea of the strength of numbers and the uniform dullness of repetition.

Quddus Mirza’s mixed medium painting, ‘In Praise of Red,’ places man in the centre of a predominantly red ground, broken up by swathes of colour. He glances towards a writing tablet inscribed with characters from the Urdu alphabet to his right. Off centre, at the bottom right of the painting, is what appears to be a death-bed scene, while on the left a disembodied head floats upside down.

Of the two installation pieces, Noor Ali Chagani’s ‘Silence’ and ‘Frozen’, are chillingly effective. ‘Silence’ is composed of a cut-away brick wall stained with tar through which one can glimpse traces of red, and ‘Frozen’ is a brick chimney filled and stopped with grey cement. Saba Khan, known previously for her witty, colourful canvases with flat planes, depicting people around her as well as personal experiences, has experimented with installation pieces using thread and fabric over the last two years. Her installation resembles an empty shroud weighted down by dangling, sometimes tangled clusters of threads and wool.

Woven into the themes of this exhibition, in art that combines modern processes with traditional form, as well as purely conceptual pieces, are telling observations — dispatches to a departed champion for the dispossessed.

Since the curator of each part of the series is different, the promise of variety within a common theme, reflecting their personal choices, is something to look forward to. The second part of the series, opening at the end of January, is curated by Umer Butt of Grey Noise, and the final show by the architect Attiq Ahmed, manager of Conservation and Community Outreach (OCCO), who works on preserving the heritage of Lahore.

This article was originally published in the February 2012 issue of Newsline under the headline “Dispatches to a Departed Hero.”