The Art of Protest

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 16 years ago

An ongoing manifestation of politically provoked art reinforces the realisation that political/social conflict is being chronically internalised within individuals.

The recent show at Canvas, “Give and Take,” goes a step further to prove that the ethos of protest is very much a live issue in the student-teacher interaction as well. Sameera Raja, as curator at Canvas, has brought together the work of four artists in accordance with her assessment of their artistic and conceptual bent. She selected educator Masuma Halai and her student, Faraz Ali, and Jamil Baloch and his student, Zahid Hussain, for a collective display. All the participants worked independently, without prior knowledge of each other’s productions, yet when seen in unison the thread of dissent ran through all the artworks.

Conflicts surrounding identity, public and personal, are a source of much concern in Masuma Halai’s work and she approaches them as a concerned citizen, a mother, a woman and a patriot. The Arab headscarf (keffiyeh), in the ‘Turban Settlements’ piece is a symbolic reference to the wave of religious extremism sweeping across the country, and its juxtaposition with photographs of architectural landmarks of Pakistan is a pointed reminder of alien influence on home ground. Similarly the ‘Domino Effect’ and ‘Shades of Black’ also reiterate the rapid and blind conversion to fundamentalist ideologies. Works like ‘The Silent Scream’ and ‘What Now’ are the other side of the story — how upheavals disrupt the lives of ordinary people. Other than the conceptual thrust, Halai’s recourse to mixed media effects in her work — painting over digital photographs, needlepoint stitchcraft and deliberate use of collage — also engage the eye. This emphasis on the ‘process’ of art-making aligns her work ethos with the printmaking genre.

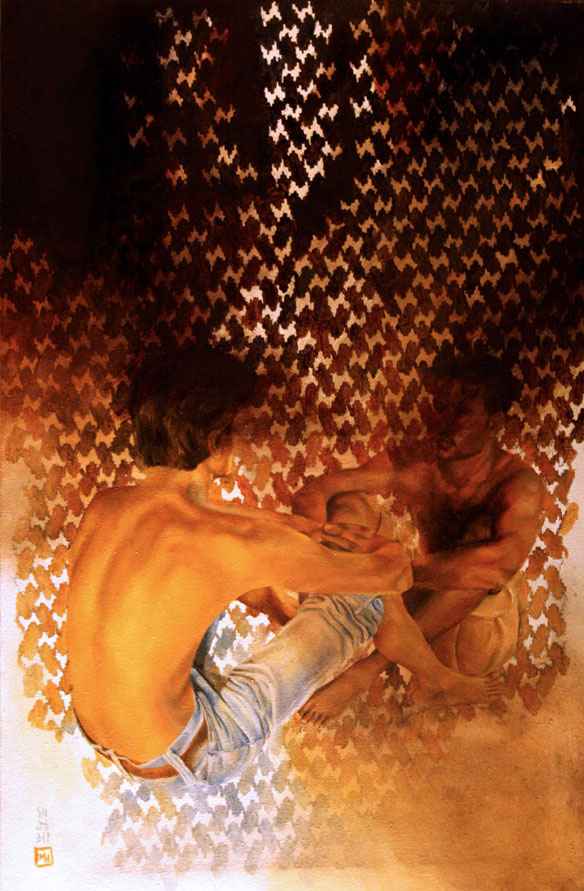

The potential one saw in the thesis projects of Indus graduate Syed Faraz Ali in 2005 is beginning to translate well in his work. Still making use of prominent political logos, emblem and insignia graphics to enunciate protest, his work, like Halai’s, also centralises on identity crisis and a partiality towards the graphic arts and print media. His use of the flag to assert identity is clever and witty. A dramatic use of the male figure and sparse but bold chromatics are other significant features that bring strength to his ink and watercolour paintings on Arches paper.

The muffled voices in Jamil Baloch’s intensely abstract “Zubaan” series are finally beginning to articulate through a distinct pictorial language. Formerly just a hash of broad and thin linear strokes in various tonalities of black, the work now supports distinct narrative content. A native of Balochistan, Jamil’s work has always been underscored with the politics of the region. He rebels against authoritarianism and oppression, but his focus on gender suppression, poverty and ethnicity are cultural discrepancies common to other regions of Pakistan as well. The accent on hope gives a positive definition to paintings in the current show. The shrouded female is seen emerging (albeit cautiously) from the shadows that once shackled her, the fighter jet missile heads now sport bouquets and sprays and the mutilated human body also rises phoenix-like as a symbol of resurrection. Most elevating is the rooster image associated with protection of good against evil. Essentially a sculptor, Jamil has been proving his mettle as a painter for quite some time and this series affirms his grasp over the medium.

The muffled voices in Jamil Baloch’s intensely abstract “Zubaan” series are finally beginning to articulate through a distinct pictorial language. Formerly just a hash of broad and thin linear strokes in various tonalities of black, the work now supports distinct narrative content. A native of Balochistan, Jamil’s work has always been underscored with the politics of the region. He rebels against authoritarianism and oppression, but his focus on gender suppression, poverty and ethnicity are cultural discrepancies common to other regions of Pakistan as well. The accent on hope gives a positive definition to paintings in the current show. The shrouded female is seen emerging (albeit cautiously) from the shadows that once shackled her, the fighter jet missile heads now sport bouquets and sprays and the mutilated human body also rises phoenix-like as a symbol of resurrection. Most elevating is the rooster image associated with protection of good against evil. Essentially a sculptor, Jamil has been proving his mettle as a painter for quite some time and this series affirms his grasp over the medium.

As a student of Jamil Baloch, Zahid Hussain draws inspiration from his mentor’s thought process but strikes a new chord with his rather radical imagery. Playing with the graphic crescent arc, he has concocted inventive narratives. Used in the political context, the star and crescent as essential components of the Pakistani flag spell the state of the nation. Reconstituting them as waves, birds and a gun trigger, the artist speaks of peace and hope under the shadow of militancy. Minimal, starkly monochrome and still striking, there is a naivety about this expression that draws in the viewer.

Unlike the bizarre and the grotesque that creeps into most conflict-riddled art, the imagery in this show was visually appealing and conformed to the dictates of contemporary realism. As a commentator on the socio-political crisis, Pakistani art appears now to seek a constructive and fruitful dialogue with viewers.