Sultana Siddiqui: Woman on a Mission

By Deneb Sumbul | Entertainment | Interview | Published 8 years ago

The writer is an activist and documentary filmmaker based in Pakistan and currently works at Newsline.

Sultana Siddiqui: Woman on a Mission

Sultana Siddiqui’s journey from producer for the state-owned Pakistan Television (PTV) to the head of a network of private channels and the recipient of numerous national and international awards, can be traced by her 40-year-long career as a media person.

Siddiqui has irrevocably and inarguably shattered the glass ceiling, and also brought down barriers of ethnic and social confinement. A fearless risk-taker with a keen sense of dramatic production, she has directed and produced groundbreaking plays that have achieved commercial success and critical acclaim with their social message. Around the globe, wherever there is an Asian diaspora, these plays attract a keen audience. Today, President of HUM Network Ltd (HUMNL) — a company she built from the ground up — Siddiqui can truly announce she has arrived. HUMNL is the only media company in Pakistan to be listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange (KSE). Its productions are watched worldwide and are being played on Netflix as well as by the Middle East Broadcasting Centre (MBC).

It has, of course, not all been smooth sailing. Siddiqui still faces daunting challenges in implementing her vision on the ground, in what is essentially regarded as a man’s world in Pakistan. But you can’t keep a dynamo down — and her journey continues…

Forty years as a producer, director, and now head of a network of channels — was your transition from a PTV producer to the President of HUM Network overwhelming?

Absolutely. Back then, becoming a doctor or a teacher were considered the only respectable professions for women. I ended up getting married pretty early and produced three children. However, my marriage didn’t work and, after seven years, I came back to live with my parents and brother.

A college associate had become a television producer and asked me to join PTV, so I went along. I ended up doing lead roles in two PTV dramas and hosted a talk show in Sindhi. Then, in 1974, PTV was hiring producers and I was asked to apply. My children were between the ages of one and six, but I applied anyway and went through a 14-month training period. One day, I saw my name on the noticeboard, alongside the list of producers who had made it. So you can say I arrived here by accident, but stayed the course because of my interest.

How did you juggle work and home?

Initially, I only produced regional programmes and the recordings would end by 5 p.m, which suited me because I was a single parent raising children. I didn’t face too many difficulties, because I lived with my parents and my brother who were very supportive.

Did you face any obstacles in the course of your work?

When I began drama production for television, some of the producers already in the field tried to limit me to producing music programmes. Others thought I should only produce programmes in Sindhi. But I had a good grasp of Urdu as well, so I saw no reason to limit myself. In 1993, I decided to remake, in Urdu, my first drama serial, Marvi, originally shot in Sindhi. That’s when I faced the greatest resistance, but the remake went on to be widely appreciated.

When did you branch out on your own?

In 1977, when General Zia-ul-Haq came to power, he created a lot of problems for PTV, the state-owned channel. And I felt the time had come for me to work on my own, so I set up a production house, Momal Productions.

My first play under that banner, called Yeh Zindagi, about a childless couple, almost didn’t make it to television. The reason proffered: “You can call a woman barren, but you cannot call a man impotent — because that is just the way our society is.” My second production, Doosri Dunya, shot in San Francisco and New York, was based on the system of lottery visas that had just been introduced in the USA.

So you established your own production house even before all the private channels opened up?

In 2000, then President General Musharraf opened up the airwaves for private channels. I had offers from other private channels to join them, Duraid Qureshi, wanted us to establish a channel of our own and had even started preparing a feasibility report for it. At the time I thought he was being too ambitious, but I must confess that I was excited about diving into the deep end. I could see the gold at the bottom.

My two daughters-in-law joined me: Momina, with a degree in finance, and Momal, who has studied English Literature, are both TV producers. I pulled in one of the country’s foremost writers, Noor-ul-Huda Shah, as our Content Head, in addition to several new writers and directors.

Your channel boasts many firsts.

Ours was the first 24-hour entertainment channel. Initially, our advisers recommended that we set up a hybrid or mixed channel like all the others. But I had seen music channels, even comedy channels abroad. Indian soaps were very popular in Pakistan at the time, so I thought, why not a drama channel?

I faced a mountain of problems. There were people who created hindrances and questioned my decision to start a channel. “We will buy all her productions, but running a channel is a man’s job, it’s not a job for women,” they’d say. But we went ahead with our plans. Always a low profile-worker, I was confident that my work would speak for itself. Since I already had a good reputation in the market, we were able to raise the necessary funds. Within two years, we were on air — albeit with little knowledge of the problems of setting up a 24-hour entertainment channel.

Six months after being on air, my son said that we didn’t have any money left to pay salaries. He requested our Chief Financial Officer and other senior management to forego salaries for some time so that the junior staff could continue receiving theirs. Banks wouldn’t extend loans for such an enterprise. He had borrowed from family and friends and even sold personal belongings. Eventually, the money started coming in.

In 2006, we decided to start a 24-hour food channel. Of course we met with the usual resistance, but HUM Masala TV was on air within 15 to 20 days. The chefs, who were unknown at the time, became celebrities and now command hefty fees and often travel around the country and abroad for food festivals.

We introduced some of the country’s most talented actors, among them Mahira Khan, Fawad Khan, Sanam Saeed, Kubra Khan and Hareem Farooq.

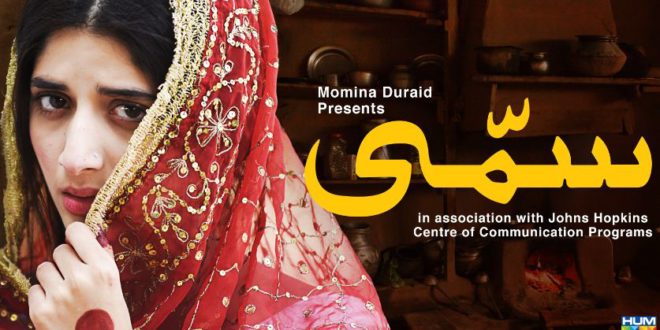

As a woman, I have consciously dealt with issues of women’s empowerment and portrayed them without crossing the red line, as in Udaari (on child abuse), Rehaai (on child marriage), Kankar (on domestic abuse), and now Sammi on the male practice of using women to compensate for their crimes. We got excellent feedback from social media, writers and NGOs for Udaari, but alongside, we got a show-cause notice from the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) — when there was really nothing in it that would offend anyone’s sensibilities.

In India, Zee TV set up the channel Zee Zindagi and broadcast our dramas such as Zindagi Gulzar Hai and Humsafar, which became hugely popular.

Ours was the first media organisation to become a public listed company at the KSE. None of the 65 Pakistani channels currently running are listed. In 2007, it was ranked among the top 25 companies on the KSE and our share prices rocketed tenfold.

Your focus has usually been women and your plays have become bolder. Have your audiences reacted negatively?

Never. That’s because I don’t resort to sensationalism. The audiences are accepting, as well as appreciative. However, when you become a challenge for other channels, they close in to thwart your progress.

Do you think women directors handle women’s issues with more sensitivity?

Earlier, I used to think so — but now I feel that some male directors have come around to our way of thinking and feeling. But I do believe that a female director would understand the pain of another woman better than a man.

Yours is truly a success story. Have you encountered any failures?

I had started a music channel, Oye, which didn’t last very long due to lack of sponsors. We converted the channel to Fashion 360, in which we included lifestyle and fashion, to help promote our fashion industry. But, unfortunately, this channel too failed, for the same reason. So we turned it into HUM Sitaray, combining drama with the lifestyle and fashion segments. This channel is doing better, but there is room for improvement.

We also took on four radio stations, but returned them because working with government organisations is very difficult and we sustained losses.

You are now in the business of cinema as well.

Two years ago, we produced our own film, Bin Roye, which was a huge commercial success. We had decided to distribute it ourselves — here and abroad — which was a first for any Pakistani film. We are now distributing films for others as well, along with another distributor, Eveready Pictures.

Currently I’m trying to convince the government not to impose taxes on the entertainment industry, especially films, for 10 years at least, to enable the industry to stand on its feet and compete with Indian cinema, which has 100 years of experience. They have a budget of 200 crore rupees for a film, while we spend 2.5 crores, or, at most, 10 crores for the bigger productions

You appear to be a woman on a mission.

Yes, absolutely. I want to pay back. My mission has always been to improve Pakistan’s image abroad — and this is not intended as a slogan. I am involved with several philanthropic ventures in education and health, but these are on a personal level. If you bring a sense of social responsibility to your work, you lift it up.

I began from scratch and rose from the ranks — I didn’t take over and sit there like a queen bee. I know the profession inside out — from direction to production; from children’s programmes to music programmes — I even created sets for plays when there weren’t enough funds. And if you ask me what I would want to do in the future, I’d say establish a media academy. These are professions where you can only learn from practical experience. Our youth have tremendous potential, if only they had a good academy.

PTV had an academy — a wonderful place in Islamabad — where only bats now nest. It has a staff of over 6,000, when a staff of 500 could easily run it.

Any other plans in the pipeline for the HUM Network?

Currently, we are not only on Netflix, but the MBC is also showing our plays, dubbed in Arabic. We are in talks for our plays to be shown in China. If foreign plays dubbed in Urdu can be shown here, there can be a reciprocal arrangement. The government can also help us with landing rights in other countries, like Turkey.

And finally, we are planning a news channel that will be very different. We intend to change the approach, to political talk shows, in particular.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.