Master Stroke

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 22 years ago

Finally the elusive Naqsh is visible in all his glory. The mystery and mastery that embody the creative endeavours of this enigmatic artist are now open for public viewing. The Jamil Naqsh Retrospective at the Mohatta Palace Museum encapsulates an aesthetic odyssey spanning five long decades. Set out sequentially, this show traces the artist’s oeuvre from its very early years to date. By the end of the ’60s Naqsh had ceased to paint for exhibitions. Well-established and highly regarded by then, his work was much sought after, especially by collectors. The bulk of his creations were now available to a private clientele only, with sporadic showings of some paintings at prestigious fund-raisers, or as national exhibits. A near hermetic existence further deepened the mystery surrounding his persona and added premium to the already inaccessible works.

Finally the elusive Naqsh is visible in all his glory. The mystery and mastery that embody the creative endeavours of this enigmatic artist are now open for public viewing. The Jamil Naqsh Retrospective at the Mohatta Palace Museum encapsulates an aesthetic odyssey spanning five long decades. Set out sequentially, this show traces the artist’s oeuvre from its very early years to date. By the end of the ’60s Naqsh had ceased to paint for exhibitions. Well-established and highly regarded by then, his work was much sought after, especially by collectors. The bulk of his creations were now available to a private clientele only, with sporadic showings of some paintings at prestigious fund-raisers, or as national exhibits. A near hermetic existence further deepened the mystery surrounding his persona and added premium to the already inaccessible works.

In 1999 the Jamil Naqsh Foundation, established to preserve his work, brought some of the artist’s art centrestage once again. However, the work of the intervening decades was lost to the public. The Mohatta Retrospective tries to fill this vacuum to some extent. They have on loan, paintings from as many as 50 private collections as well as the Naqsh Foundation. On view is a cache of 600 artworks, some of which have never been exhibited publicly before. This temporary transfer of private holdings to a public sphere endows the retro show with a “must see” status. Such a thematically and chronologically arranged collection is a rare event, not likely to recur for quite some time to come. This planned and deliberated event owes much to the mature aesthetic vision, foresight and consistent efforts of curators Marjorie Hussain and Nasreen Askari.

Jamil Naqsh, the artist, belongs to the old cadre of painters whose expression evolved from the ustad-shagird relationship. As a student at Mayo School of Art, Lahore, in the early ’50s Naqsh got his first whiff of modernism when pioneer modernist Shakir Ali was introducing his concepts of cubism. Simultaneously, miniature art, under the guidance of the renowned Haji Shariff, was also an essential part of the school curriculum. Keeping in mind the traditional and literary ambience of Kairana, the artist’s childhood home in India, Naqsh’s love for the classical and oriental in arts was a very natural preference. Abandoning his study courses at Mayo he commenced a two-year apprenticeship with Ustad Shariff. Imbibing the skills of this arduous discipline had significant, far-reaching effects on his development as an artist. All his subsequent innovative phases are directly or indirectly related to some element of this finely wrought exercise.

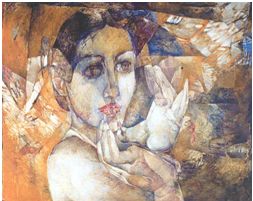

Pigeons were the first pictorial motif borrowed from the miniature picture frame. They were also among Naqsh’s earliest companions from his childhood days in Kairana, where pigeons roosted in the courtyards and flew freely through open windows. And then their universal significance as heralders of peace and harmony in the aesthetic vocabulary was already there. In the early ’60s, when his celebrated pigeons first emerged on canvas, a leitmotif was born and with it came the flutter of recognition, popularity and success. The birds swooped, cooed and nuzzled their way into his compositions, and were imparted in the process an aura of romance, lyricism and harmony. For years to come they were emblems of the Naqsh mystique, his most faithful friends in his affaire de coeur. He painted them in flight and at rest, in watercolours, oils, ink and wash. At Mohatta, Galleries 1 to 4 have the most attractive specimens of these endearing creatures in crude impasto and finely chiselled brushwork. An entire wall in Gallery II, dedicated to over two dozen takes of a single pigeon, reveal a master’s obsession not just with the subject but also with the painterly process. Like a conjuror, Naqsh is able to bring infinite variation in colour and presentation, to a single object.

Pigeons were the first pictorial motif borrowed from the miniature picture frame. They were also among Naqsh’s earliest companions from his childhood days in Kairana, where pigeons roosted in the courtyards and flew freely through open windows. And then their universal significance as heralders of peace and harmony in the aesthetic vocabulary was already there. In the early ’60s, when his celebrated pigeons first emerged on canvas, a leitmotif was born and with it came the flutter of recognition, popularity and success. The birds swooped, cooed and nuzzled their way into his compositions, and were imparted in the process an aura of romance, lyricism and harmony. For years to come they were emblems of the Naqsh mystique, his most faithful friends in his affaire de coeur. He painted them in flight and at rest, in watercolours, oils, ink and wash. At Mohatta, Galleries 1 to 4 have the most attractive specimens of these endearing creatures in crude impasto and finely chiselled brushwork. An entire wall in Gallery II, dedicated to over two dozen takes of a single pigeon, reveal a master’s obsession not just with the subject but also with the painterly process. Like a conjuror, Naqsh is able to bring infinite variation in colour and presentation, to a single object.

If pigeons were Naqsh’s supporting cast, then surely it was the female nude who was his leading lady, his muse, his object of desire. In the early years, she was long-limbed, sharp-clawed, flat-chested and grim-faced. Some frightening specimens hung in this show help to trace his gradual development towards the evocative and the ethereal. Still mute with sad soulful eyes, the nude gradually acquired tender, soft, misty contours exuding an intensely sensuous aura. A woman in love was painted by an artist in love with love. Searching for a stronger metaphor than just the poetic sensitivity of woman and pigeon, Naqsh evolved the ‘Woman and Horse’ series. Rejecting Asian and subcontinental configurations, he took inspiration from the bold modern language of sculptor Marino Marini’s imagery. Without lifting any elements from Marini’s oeuvre, he worked out original compositions charged with fusion, harmony and wholeness. The horse was now his symbolic emblem of the male presence which encompassed, enslaved and accompanied the nude in a variety of mannerisms. He probably executed some of his most erotic pieces during this period. Very graphic, some works from ‘Woman, Prajna and Paramita: An Ode to Love’ series are under lock and key at Mohatta and can be viewed by appointment only. Clasped lovingly, locked in embrace or just together, Naqsh enacts a biological bonding of another nature in his ‘Mother and Child’ series, by juxtaposing nudes with newborns. Another emblem, another face of love and yet some more experiments in modern expression. This series dedicated to his friend Dr. Sethna is yet another example of his constant quest to explore new spatial and emotional dimensions.

Shifting focus to the purely grammatical, Naqsh’s ‘Manuscript’ series stands out as a bold technical experiment with the Arabic script. Not just content with modernising it as most contemporary calligraphers have done, he reinvents the idiom entirely, forsaking legibility to create his own complex interplay of signs and symbols.

Naqsh’s love for the materiality of paint and his romance with the painted surface is as crucial to his oeuvre as his emotive sensibility. Textural manipulation, from the abrasive, grainy and heavily sedimented to the delicately packed and pointillated, has not only given strong stylistic definition to his work but has also been instrumental in expressing his various moods and phases. Pearly, marbelised surfaces contrast sharply with heavily-worked layered pigmentation, and the finely speckled surfaces instantly remind one of the single hair brush used in miniature painting. Add to all this a very mature sensitive feel for colour and we have a master on our hands — one who is not afraid to experiment, grow and regenerate in his quest for the eternal.

No more posts to load